In 2002, filmmaker (and Moviefone founder) Andrew Jarecki began to shoot a documentary about New York birthday clowns. While working with one of the city's most popular bozos, David Friedman, Jarecki noticed several offhand comments Friedman made about his family -- something about his father, something about an injustice. When Jarecki inquired further, Friedman merely said there were some things he would rather not get into.

So, like any budding Errol Morris, Jarecki got into it. Research revealed that David's Long Island family had been destroyed in 1987 when his father, Arnold, and younger brother Jesse were accused of hundreds of appalling crimes. The charges included possession of child pornography and the sodomizing of dozens of young boys enrolled in Arnold's home-school computer class.

Jarecki switched the focus of his film to the Friedman case, whereupon David presented him with 25 hours of home videotapes shot contemporaneously by family members during the crisis -- discomfiting, surreal footage of vicious arguments, shifting loyalties and grossly inappropriate mugging. This first-person depiction of the family's implosion is as close to "snuff" as you will ever want to see, and is the most chilling use of amateur video since "The Blair Witch Project."

By combining these home movies with the Friedman's old 8mm reels and personal video diaries -- plus an overwhelming collection of TV news footage and courtroom video archives -- Jarecki makes an unsettling bio-technological discovery: A camera is a camera; the human brain is also a camera. Both run on electrical impulses. And both are infinitely fallible when employed to recover "the truth."

Both Arnold and Jesse Friedman pleaded guilty to numerous heinous charges of abuse. Arnold died in prison in 1995 and Jesse served 13 years in prison before his release in 2001. But the question of whether they were really guilty of these dreadful and dramatic crimes is, to put it mildly, called into question by Jarecki's exploration of the case.

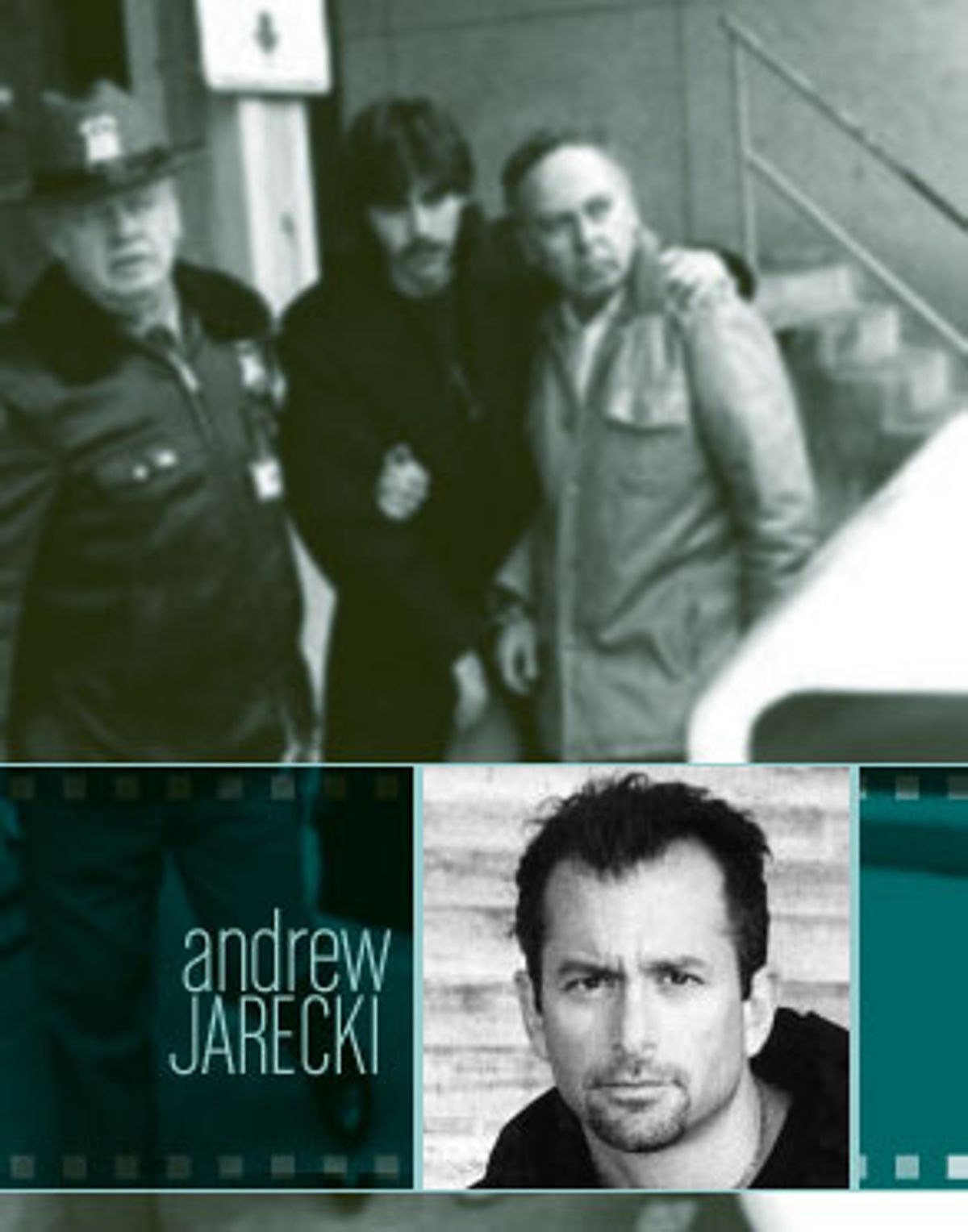

The result of Jarecki's efforts is the startling film "Capturing the Friedmans," which won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival. It opened last weekend at the Angelika Film Center in New York, where it broke the house box-office record for a documentary (set a year earlier by Michael Moore's "Bowling for Columbine"). Openings in many more cities will follow. I spoke with Jarecki in Chicago.

America in 1987, when the Friedman case broke, was really at the dawn of home video culture. Our obsession with recording every "significant moment" of our lives is still growing. Why is that?

A big theme in the movie is the transient nature of memory; the ephemeral nature and dynamic nature. People talk about a "memory bank" like it's a place where your memories sit static, but the reality is that as soon as you have an experience and it goes into your memory, it becomes just another electrochemical impulse, and it sits there bubbling like any other chemical reaction. Your memories evolve over time. I think recording is our effort to prevent that in some way. Certainly this [happens] in the film, when David says, "Maybe I shot the videotape so I wouldn't have to remember it myself."

Do you think the Friedman family was conscious that the camera lens was shielding them from the terror and confusion they should be feeling?

Well, David would tell you that they were just recording themselves because their father was going to jail and they wanted to record his last moments with his family, and you can understand that. At the same time, there's also that feeling that so much was going on in their lives at that moment -- it was so confusing, every day there was a new accusation or a new newspaper article -- that you can also imagine they wanted to codify the past, they wanted to have a record they could go back to. They saw members of the family going away and knew [the family] was about to be destroyed. So I think they were clinging to those moments and saying, "Well, let's capture them, and maybe later we can understand them better."

OK, but now that they have seen the footage again, 16 years later, do they realize their home video recording habits were unusually intrusive and intimate?

They would say that the family was very theatrical to begin with. In the opening of the movie, you see these credits that they made in their own home movies, in happier times. They'd put up a big poster board in the street and they would write "Presented by the Friedman Family," and then somebody off-camera would throw a basketball and knock it over. They were creative. They had a lot of good ideas. And they liked seeing themselves on film.

So they were well trained -- it was like being trained for battle or something. Suddenly this thing that was all about the comedy of being able to record home movies comes in handy and is like really, really important. There is a feeling, I think, that 10 years from now all documentaries will have this first-person camera component. But at the time the Friedmans were doing it, they were the vanguard, they were really on the cutting edge of self-documentation. They were ahead of the curve, although it's kind of tragic.

One of the most troubling things about the Friedmans' home videos is that they often appear to be making light of their horrific situation. The most glaring example of this is when Jesse is awaiting sentencing, and he's performing a Monty Python skit for his brothers on the courthouse steps.

That's certainly a moment that is play-acted intentionally, because they've been waiting for three hours to get in the courthouse and they're pretty freaked out and nervous. I understood that perfectly. The people who were watching them from the courthouse said, "Well, those kids are completely out of touch with reality." And once you believe someone is crazy, you can believe that they're capable of anything -- and that was what happened in the investigation.

For example, you see this moment where David puts a pair of underwear on his head and walks around the front yard yelling at the TV cameras [when his father, Arnold, is first arrested]. If you believe the detective, David was reverting to an infantile state. That indicates that, well, he and his family members are not only crazy but crazy in such a way that underwear is implemented -- "Aha!" But a second later in the film, David says, "There were 25 TV cameras. I reached into my bag and the first thing I came out with that I could put over my head was underwear."

It's hard not to compare your film with reality television. It's like what might happen if the Osbourne family were suddenly charged with gruesome sex crimes.

That's a fair characterization, but I also think the film is kind of epic and biblical and tragic; I really think it's a Greek tragedy meets "The Osbournes." There certainly is that voyeuristic quality. But I think here the stakes are so much higher -- there were consequences, a family was destroyed, countless other families left the process believing that incredibly horrible things happened to their children, people ended up in jail, people ended up dead! You watch reality TV and the highest stakes are, "Is the girl going to get the bachelor?" Then they're off to Cancun where you're not going to see them again, and you're going to turn on the next show.

With my film you don't walk away thinking, "Well, I don't know what happened, but who cares? Let those people rot in jail, let those other people feel like they were molested." You feel you have to have an opinion. I think that's what they're searching for, frankly, in reality TV: Making people care about the characters and not just making it some momentary spectacle like "Jackass."

I suppose the difference is clearest right at the beginning of the film, when David, in his video diary, says to the camera, "This is private. If you're not me, turn it off."

Yeah. Even in today's world of reality TV, it's OK to see somebody buried in a shallow grave with maggots all over them because that's their biggest fear. But when somebody says, "I don't want to be seen right now," it still grabs us a little bit.

Shares