“The Kid Stays in the Picture,” Brett Morgen and Nanette Burstein’s documentary about legendary Hollywood producer Robert Evans (which opens this week in New York, with more cities to follow), is clearly 2,000 percent baloney. Well, maybe 1,999 percent. It’s true that Evans started out as a not-very-scintillating actor (he made his debut playing movie mogul Irving Thalberg in the 1957 “Man of a Thousand Faces”; he was handpicked by Thalberg’s widow, Norma Shearer). It’s also true that he proceeded to produce some of the most hugely successful — if not always the best — movies of the 1970s, among them “Chinatown,” “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Love Story” and “The Godfather.”

But there are times when baloney tells a better story than fact ever could, and “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” narrated by Evans himself, is one of them. Evans sells himself to us in exactly the same way you imagine he might have sold one of his hit pictures to the bigwigs at Paramount during his golden years. It’s not that Evans’ recollections are completely suspect; it’s simply that his delivery is so jazzy, so freestyle, that you figure no one (least of all himself) would ever want to fact-check the details — getting the absolute, undecorated truth would be too crushing.

In fact, I’m sure it’s intentional that we’re supposed to start out watching “The Kid Stays in the Picture” skeptically, only to be lured in by the details Evans lays out for us like so many delectable bread crumbs. His version of events raises so many red flags that after a point they become the grand action of the movie, a beautifully choreographed routine by themselves — the Dance of the Red Flags, you might call it.

Beyond that, the movie opens with an epigraph from Evans that tells us outright it’s more about perception and memory than it is an ironclad recounting of events: “There are three sides to every story: My side, your side and the truth. And no one is lying. Memories shared serve each one differently.” And so in his inimitable, showbiz swinger, cracked-pepper voice, Evans rattles off an amazing number of stories, including the one that explains the movie’s title (which is also the name of his 1994 autobiography).

Evans was almost kicked off his first big movie as an actor, the 1957 “The Sun Also Rises,” when a number of the movie’s stars, as well as Ernest Hemingway himself, signed a petition claiming that he was all wrong for the role of bullfighter Pedro Romero. The movie’s producer, Darryl Zanuck, would take a look at the young Evans and make the ruling. “Suddenly Zanuck stands up, all 5-foot-3 of him …” is how Evans begins the sentence.

Zanuck’s final decree was that the kid should indeed stay in the picture, but the moment was significant for Evans for another reason: He knew at that moment that he didn’t really want to be an actor. He wanted to be the guy who gets to say, “The kid stays in the picture.”

From there, Evans recounts how he came to power in Hollywood: As head of production at Paramount in the late ’60s and early ’70s, he boosted the studio’s rank at the box office from No. 9 to No. 1. Evans was cast in the mold of the old-time showman. He knew what audiences wanted to see (even when they didn’t know themselves) and he gave it to them in pictures like “The Odd Couple” (1968), “Goodbye, Columbus” (1969) and “Serpico” (1973), as well as, of course, “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968) “Love Story” (1970) and “The Godfather” (1972). His first picture as producer — under his own company, Robert Evans Productions, set up at Paramount — was “Chinatown” (1974).

Evans rode high, which of course meant he would fall hard. He was busted for cocaine in the early ’80s, and became involved in a mysterious Hollywood murder case that’s only sketchily explained in the movie. (He was never actually a suspect.) Over the years he bought, lost and recovered an incredible-looking (in its own vaguely tacky way) Beverly Hills house known as Woodlands. He spent time in a psychiatric hospital. After disappearing from Hollywood for years, he returned to produce pictures like “Sliver” (1993) and “The Saint” (1997).

Burstein and Morgen (who previously directed the 1999 boxing film “On the Ropes”)are the ideal documentary filmmakers: in other words, invisible ones. They’ve given Evans’ material shape and momentum — the picture moves along swiftly — while preserving the illusion that all they’ve done is simply wind him up and let him go.

Admittedly, Evans probably doesn’t need much winding. He talks a blue streak — he’s Borscht Belt by way of Sunset Boulevard. As much of a raconteur as he is, though, he always comes off as a real person, albeit one who’s larger than life. Evans was married and divorced five times, but “The Kid Stays in the Picture” deals with only one of those marriages: He wed Ali MacGraw in the late ’60s, only to lose her to Steve McQueen a few years later.

Evans talks about MacGraw (he calls her “Miss Snotnose”) with a gruffness that can only be interpreted as true affection. And when he talks about how it felt to lose her, you could argue that he’s putting on a show for the sake of the movie. Or you could recognize that, whether it’s part of the show or not, the way he takes responsibility for the failure of the marriage is at the very least a sincere, gentlemanly gesture.

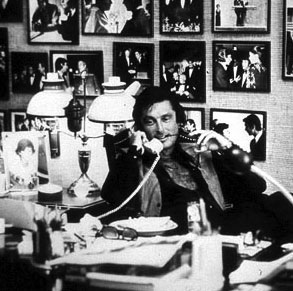

The visuals in “The Kid Stays in the Picture” consist of scenes from Evans’ movies; pictures and clips from the press; and period TV footage of Evans wearing an increasingly outlandish array of giant tinted specs and open-necked shirts whose collars look like they could take flight in a good stiff wind. From his wardrobe to his storytelling, Evans was, and is, the consummate showman.

He is also, I’m afraid, the last of a nearly extinct breed. Evans may have made history in Hollywood; he also made his share of crap. But in addition to having an eye and an ear for what would sell, he also had a sixth sense about what audiences should want to see — and he made them want it.

With the exception of the drippy weeper “Love Story,” his most successful pictures — the others would be “Chinatown,” “Rosemary’s Baby” and “The Godfather” — are all movies that stand up to close scrutiny today. Audiences still love them. But as great as they are, I’d venture that not one of those movies could get made today. “The Godfather” and “Chinatown” would be considered too complicated, “Rosemary’s Baby” too oblique.

Evans was the ideal producer because he had unswerving faith in the audience’s ability to get it. And for a pretty astonishing stretch of years, they didn’t let him down. It only makes sense, then, that a documentary about his life should be as purely entertaining as any Hollywood invention. “The Kid Stays in the Picture” may be baloney. But it’s all beef, and no bull.