Any filmmaker who feels the need to explain a talking fish has no business making a movie of “The Cat in the Hat.” In the world of Dr. Seuss, there’s no more need to explain a talking goldfish who warns his people against the shenanigans of a 6-foot-tall talking, juggling cat than there is to explain … a 6-foot-tall talking, juggling cat.

In the dreadful new big-screen version of “The Cat in the Hat,” as soon as the fish opens his fishy mouth to burble out a fishy warning, there’s a cut to the little boy and girl he lives with (Spencer Breslin and Dakota Fanning) with the requisite amazed look on their faces, followed by the inevitable equivalent of “Hey! The fish can talk!” (Of course he can talk, you wretched little nits — you’re in a Dr. Seuss story.)

It’s a small moment, but it sums up exactly what’s wrong with this film: It was made by people who can’t give themselves over to the logic of Dr. Seuss’ skewed storybook world. Instead of simply allowing strange and wonderful things to happen, they have to tell us strange and wonderful things are happening. And then, because, of course, we all know that today’s kids are media-savvy little meta-boogers, they have to provide fourth-wall-breaking asides and wiseass jokes, which puts everything in quotation marks and trashes what little fantasy has made it to the screen.

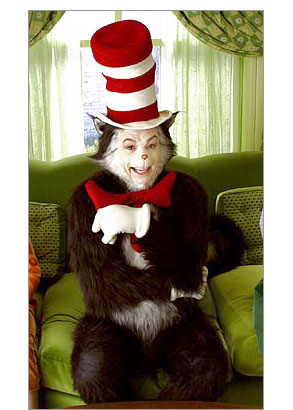

“The Cat in the Hat,” which was directed by Bo Welch and adapted by Alec Berg, David Mandel and Jeff Schaffer, is like a perverse new variation of Manny Farber’s famous definition of “termite art,” meaning art that eats through the barriers other art defines itself by. This movie eats itself. You see the millions of dollars spent on the Candy Land production design (by Alex McDowell) and the special effects and the makeup that transforms star Mike Myers into the cat, and you’re not for a second meant to believe any of it. The movie is crass and vulgar almost beyond belief.

I enjoy raunchy humor, and I don’t necessarily believe kids need to be protected from it. But the raunchy humor here is antithetical to the spirit of Dr. Seuss, and it’s likely to sail right over the heads of the kids in the audience. So who is it meant for? The adults who are going to take their kids over the upcoming holiday vacation? Maybe, though it might make them uncomfortable to hear some of this stuff with their kids around. The jokes seem more like the filmmakers’ way of saying, Hey, we may be making a kids’ movie, but we’re not goody-goodies.

Is there any other reason for a framed picture of the kids’ mother (Kelly Preston) to open up like a centerfold, causing the Cat’s crumpled, striped top hat to shoot straight up in the air? Is there any reason for Mike Myers to stop in the middle of one scene to plug the Universal Studios theme park (Universal, along with DreamWorks, is releasing the movie) other than to A) get in a product placement and B) claim that he’s satirizing product placement? What’s the point of a club scene except to provide an excuse for a cameo from Paris Hilton? (And, really, who cares?) I laughed at some of the jokes here — a few politically incorrect moments with a sleepy Asian baby sitter, and some of the stuff Alec Baldwin does as the creep next door who’s dating the kids’ mother — but I felt cheap for laughing.

Welch and his team don’t get anything right. The cinematography, by the gifted Emmanuel Lubezki (best known for his work with Alfonso Cuarón), is intended as a powdery pastel travesty of the storybooks and ’50s advertising illustrations of suburbia. The colors pop out at you, and they’re entirely wrong for the muted palette of Seuss’ children’s classic. Lubezki throws all the screaming pinks and lime greens and bright purples he can onto the screen, and they’re no match for what Seuss got with black and gray and red and blue. To include the strange curves and angles of Seuss’ world, the movie resorts to a subplot about the entire house being sucked into an alternate dimension — another example of the moviemakers trying to explain things that simply happen in the book.

Expanding a storybook of a few hundred words into a 73-minute movie necessarily means expanding the story. But was the little object lesson the filmmakers have come up with the only way to do it? The two children here are Conrad (Breslin), a budding sociopath, and Sally (Fanning), a good-doobee little creep who plans out her day on a PalmPilot. (All I have to say about this preternaturally seasoned child performer is: I do not like this girl Dakota. I do not like her one iota.) They’ve been warned to keep the house neat because their mom’s persnickety boss (Sean Hayes) is coming over that night. As in the Seuss original, the Cat wreaks havoc in the house with the aid of two strange little mnookins, Thing One and Thing Two. (Their movie incarnations are really creepy — as if some movie-mad makeup artist had melded the masks from “Planet of the Apes” and “Eyes Without a Face.”)

But unlike the book, the movie has a little lesson to impart. Conrad has to learn that fun has its limits, and Sally has to learn to be spontaneous. What’s more, they have to learn to — gulp — like each other. Movies that set out to teach a lesson are a drag to begin with. When that goody-goody lesson comes after an hour and a quarter of lamebrained gags, it’s like being in the presence of one of those ancient Catskills-Vegas blue comedians who ends his act with a brotherhood speech.

What’s especially depressing about “The Cat in the Hat” is that here, that old Vegas hambone is Mike Myers. At first, Myers seems to be taking an approach to the character, even if it’s all wrong. Speaking in an accent that sounds as if he’s still doing Linda Richman from “Saturday Night Live’s” “Coffee Talk,” Myers uses the Cat to spout a Borscht Belt-style showbiz shpritz. He’s so fast, veering between leg pulling and faux sincerity, that the very inappropriateness of the performance for a kids movie makes you giddy. It gets wearying fast, though, and Myers winds up doing something he’s never done before — begging the audience to find him adorable. Myers cheapens his talent in “The Cat in the Hat.” He’s done far raunchier material in the “Austin Powers” movies, but the jokes here lack the sweet-spirited silliness of those movies. This performance is self-aware in a way that’s fatal to comedy.

During his lifetime, Dr. Seuss was notoriously picky about allowing adaptations of his books. That worked in everybody’s favor, giving us Chuck Jones’ great version of “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” and the Camden recording of what for me is Seuss’ masterpiece, “Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book,” narrated by Marvin Miller with music by Marty Gold. Seuss’ widow, Audrey Geisel, has not shown anything approaching her late husband’s taste. She OK’d the stinkburger Ron Howard and Jim Carrey remake of “The Grinch,” as well as this movie. Others will presumably follow. “The Cat in the Hat” is the best argument yet made for extending artists’ rights beyond the grave.