When we talk about a lost masterpiece, we’re usually thinking of, or at least hoping for, a treasure that exists somewhere in a close-to-perfect form, if only we could find it. With movies, it’s almost never that easy.

“Major Dundee,” Sam Peckinpah’s first large-scale western, is a lost masterpiece of the imagination. When it was released, in 1965, the picture was rejected by critics and audiences alike, but not because Peckinpah had fallen down on the job. The picture was beset by problems from the start: Its studio, Columbia, cut its budget by a third before filming had even begun. And beyond the fact that certain key scenes were never even shot, the picture was taken from Peckinpah and cut by some 20 to 50 minutes before its release. As it was originally seen, “Major Dundee” had some baffling gaps, and historically, it has been treated as a potentially great picture and a frustrating disappointment.

Sony Pictures has at last redressed — or attempted to redress — the sins of its corporate fathers by restoring as much as possible of Peckinpah’s original cut and commissioning a new score — a fine one, by Christopher Caliendo — more in keeping with the spirit of the picture. “Major Dundee: The Extended Version” — which opens Friday in New York at Film Forum, and April 15 in Los Angeles and Boston, to be followed by stints in other major cities thereafter — isn’t the model of clarity that Peckinpah fans may be hoping for. While the plot is easy enough to follow, the second half of the picture still doesn’t come close to fulfilling the promises of the first, suggesting that while the studio’s butchery certainly didn’t help “Major Dundee,” some of the movie’s problems may have been rooted deeper in its conception.

But the flaws of “Major Dundee” don’t begin to nag at you until after the fact: As the picture unfolds, for the first hour at least, it has the look and feel of a masterpiece — it’s a picture rushing toward something, and despite the grave disappointment that it never quite gets there, you never doubt you’re in the presence of greatness.

Charlton Heston stars as Amos Dundee, a demoted Union officer who’s been put in charge of a prison filled with lowlifes. A group of renegade Apaches have just led a massacre on a New Mexico settlement; Dundee has been assigned to rescue two young boys who have been abducted (the rest of the settlement has been killed) and to capture or kill the group’s leader, Sierra Charriba (Michael Pate).

It’s late 1864, and the Civil War has drained the supply of good, able men. So in order to complete the assignment that will restore his honor — in his own mind, at least — Dundee assembles the best team of men he can find, which includes several dutiful Union officers (played by Michael Anderson Jr., Brock Peters and the great Jim Hutton), a leathery, one-armed scout (James Coburn), assorted horse thieves and drunkards (played by the wonderful Peckinpah regulars Dub Taylor and Slim Pickens), and a group of scruffy, stubborn Confederate prisoners (among them Warren Oates and L.Q. Jones) led by Captain Benjamin Tyreen (Richard Harris), who’s so reluctant to serve the enemy that he asks to be put to death instead: He’d rather fight than switch.

But Dundee needs Tyreen desperately, and the conflict between the two is what gives the picture its rustic delicacy and emotional sharpness. Dundee and Tyreen have a murky past: They were formerly friends and West Point classmates, but Dundee can’t forgive Tyreen, an Irish immigrant, for going off to fight for the wrong side. The fractured friendship between the two men intensifies their differences: Tyreen is something of a rapscallion, but he’s also a spirited, visionary leader who has earned the respect of his men. Dundee is obstinate and literal, and he demands obedience, but we get the sense he was once something more — some wartime disgrace or horror has eroded him, but we don’t quite know what it is.

Unfortunately, Dundee is set up to be a more complex character than he ever turns out to be. At the beginning we see him as noble, reliable and steadfast, but he’s also a cracked man. Armed with those shorthand clues, we keep waiting for him to become interesting, and he never does. Meanwhile, Tyreen, whose sexual charisma is a chief component of his leadership qualities — not even Dundee can resist him — holds us in a fugue state of anticipation. What will he do next? When will we see him again? He’s the devilish boy who leaves us hanging, delectably.

Still, Dundee’s inner torture remains the movie’s focus, and there’s never any release valve for it. When the movie ends, we understand him less than we did at the beginning — and, even worse, we care for him less. It’s nearly incomprehensible that the luscious Senta Berger, as a no-nonsense doctor’s widow in a Mexican town, chooses the solid, dutiful, dull Dundee over Tyreen, the devilish rake. She needs duty, honor and reliability in her life: She’s just that kind of woman. But even if it makes sense for the character, it’s cinematically numbing.

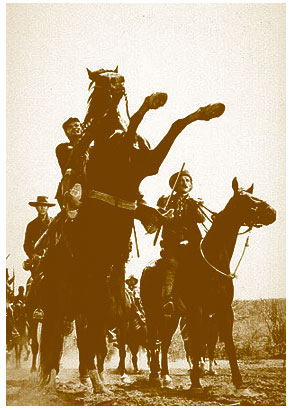

The common wisdom about westerns — at least among people who have never actually seen one — is that they’re all about action and not at all about character development or human relationships. Tell that to Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher or Howard Hawks, who made ’50s westerns that revealed the underlying tensions and anxieties of an incredibly complicated era. And Peckinpah, who made the greatest westerns of the ’60s, is best known (and often conveniently dismissed) for the balletic violence of his movies, but he’s really all about relationships. Maybe that’s why the failings of “Major Dundee” are so frustrating — the battle sequences, particularly the climactic clash between Dundee’s raggedy men and a dazzling brigade of French lancers, are as beautifully executed as you’d expect from Peckinpah. It’s the love story — and I’m talking about the one between Dundee and Tyreen — that’s disappointingly soft and shapeless.

Then again, maybe that’s where the real value of “Major Dundee: The Extended Version” lies — in the way it forces us to confront the conflict between the movie in front of us and the movie we wish we were seeing. Not even this extended version is the picture Peckinpah intended, a fact that those who restored it (beautifully, by the way) freely admit: In the press notes for the movie’s Film Forum release, Sony’s Grover Crisp speaks of having created “a longer and, hopefully, more authentic version of the film.” This extended “Major Dundee” is, he notes, “an attempt to restore a film that was never really completed, and for which there can never be any truly definitive version.”

Since “Major Dundee” was so heavily compromised from the very start — and even this new version is still missing original footage — we can assume that what we’re seeing isn’t even close to the picture Peckinpah had originally meant to make. But at the very least, this extended version gives us a chance to bask in the magnificence that is there. Even if the picture falls apart in the second half, the first half is loaded with individual scenes that are beautifully staged and acted. A rousing fiesta sequence is marked by a creeping sense of dread, presaging the fiesta scene in “The Wild Bunch.” And a sequence in which one of Tyreen’s coarse, surly soldiers demands that a black Union soldier (played by Brock Peters) kneel down and remove his boots plays out with such tightly coiled tension that it’s almost like a mini movie in itself: Its rhythms are marvelously controlled and sophisticated.

And then there’s the look of the thing: Shot by Sam Leavitt in a palette of dusty grays and muted sand tones, “Major Dundee” features so many gorgeous compositions that it’s easy to lose yourself in them. The landscapes in the picture are so vital they practically breathe, yet they never detract from the actors. And both Heston and Harris easily live up to the beauty of those landscapes.

Even though the material lets Heston down in the second half, in the first half, he’s a repository of thorny masculinity, someone whose secrets we want to know. What has broken him? And why is he so driven to fight this particular enemy? Heston is stunningly handsome here, a dusty sun god of the West, and Peckinpah and his camera are wholly alive to his masculine beauty. (It’s also important to note that, when the studio threatened to pull the plug on “Major Dundee,” Heston paid back his own salary so some crucial missing scenes could be shot. The studio took the money and failed to film the scenes, but Heston’s actions stand as a testament to his commitment to the picture, and to Peckinpah.)

As stunning-looking as Heston is, though, Harris — a very young Harris — still manages to steal the movie, and not just on looks alone. Harris delivers his lines as if all the West — not just the West of the western-movie tradition, but all of Western culture — were his stage. Without coming off as overrefined or highfalutin, he brings a Shakespearean prickliness to the picture. In one of his finest moments, he assures Dundee he will never fight for the North. The United States is “not my country,” he asserts. “I damn its flag and I damn you. And I would rather hang than serve.” The words ring out in ripples like the peal of a bell, a sound that could stretch from sea to shining sea and back again. Harris looks regal, even in the tattered officer’s uniform he wears at the beginning of the picture. He’s the perfect embodiment of one of Peckinpah’s favorite themes — the way stalwart values like honor and loyalty remain durable and valuable even when the civilized fabric around them has been cut to ribbons.

Or especially when that fabric has been cut to ribbons: Notions of honor and loyalty are easy enough to cling to when things are going smoothly; it’s when civilization goes askew that they’re most needed. “Major Dundee” should have been one of the great movies of the ’60s. As it is, it’s half a great movie. But in the real world we live in — one in which artistry is so often betrayed and craftsmanship butchered — even half a masterpiece is better than none. As flawed as it is, “Major Dundee” maintains its dignity in the face of the injustices that were done to it. Ripped-up and ragtag, it still holds its head high.