Ang Lee's "Taking Woodstock" is a gentle film that tells the story of how one Elliot Tiber -- born Elliot Teichberg -- helped a group of ambitious festival organizers find a site for their concert and a place in history. It's a nice little story, all right. But "Taking Woodstock" is so gentle it barely has enough vitality to stick to the screen. It's harmless enough as a snapshot of a young man's awakening to the grand possibilities of adult life, but not particularly effective at capturing the spirit, the thrill or even the mud of this culturally monumental event.

Of course, if that's what you're after, Michael Wadleigh's 1970 documentary "Woodstock" is the place to go. Lee seems to know he can't compete with it, so he doesn't try (although he does borrow some of its key elements, particularly Wadleigh's use of split-screen effects). Yet his low-key, free-spirited approach feels dispassionate and disconnected. The movie's uncharismatic center is Elliot (Demetri Martin), who's already left his parents' home in the Catskills to avail himself of the freedom and excitement of Greenwich Village. Or, rather, he has almost left home: He's called back one summer to help save the family business, a decidedly unglamorous "resort" -- in other words, motel -- that his parents, Jake and Sonia (Henry Goodman and Imelda Staunton), have allowed to fall into disrepair over the years. Facing several months, perhaps even a lifetime, of stifling boredom, even as he's striving to put his family's finances in order, Elliot finds a welcome window of opportunity when he learns that the promoters of an upcoming music and arts festival, scheduled to be held in nearby Wallkill, New York, have lost their permit for the event. He calls its producer, Michael Lang (Jonathan Groff), to offer his family's motel as a base for his staff. He also introduces Lang and his groovy colleagues to a nearby dairy farmer, Max Yasgur (Eugene Levy, in a characteristically deadpan, and wonderful, performance), who meets with the kids, deems them A-OK, and agrees to let them use his land for their show -- provided they clean up after themselves and, of course, pay a small fee (which he later increases).

And so this peace-and-love happening that almost wasn't comes together rather quickly. Meanwhile, Elliot grows up, loosening his connection to his parents, which threatens to strangle him. He even meets a nice boy, a hunky jack-of-all trades type (played by Darren Pettie) who's come to help make preparations for the concert. They meet each other's gaze over a Judy Garland record, and it's love (or at least lust) at first sight.

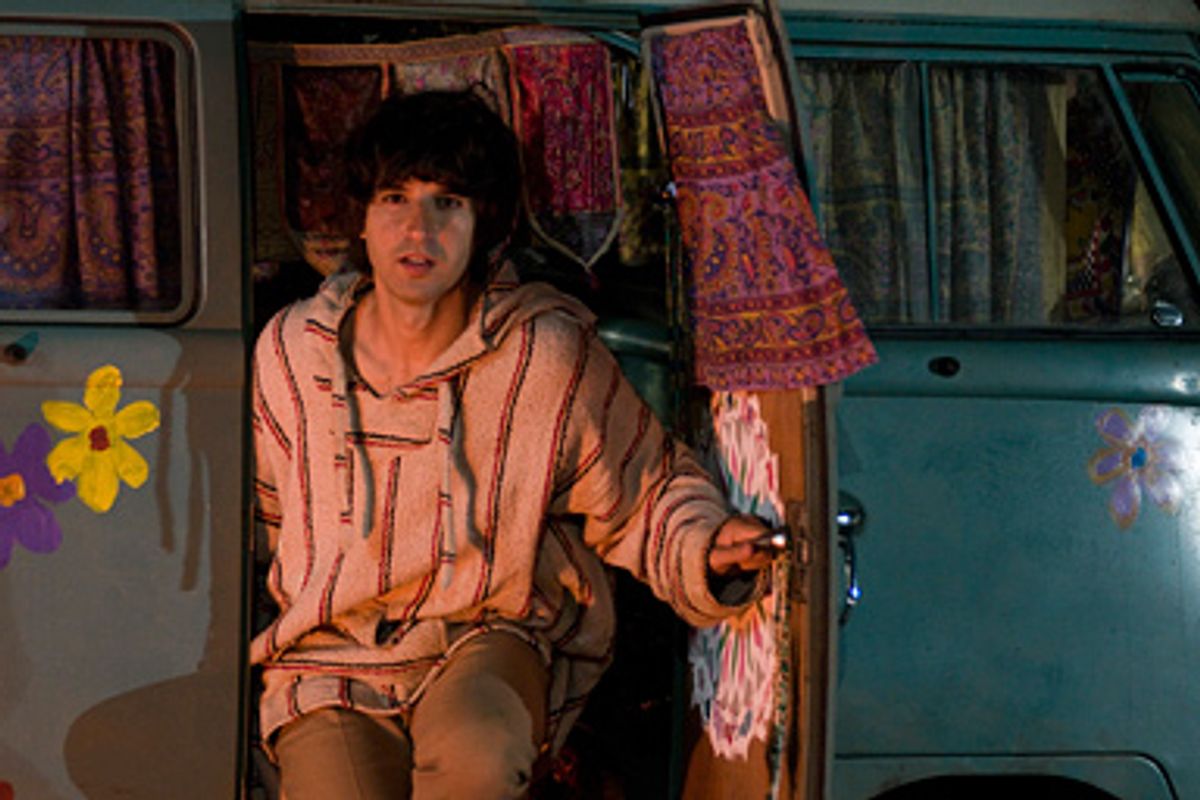

In "Taking Woodstock," the concert itself is pretty much an afterthought, which would be OK if it were easier to muster more sympathy for Elliot. But he's a bland, watery character: Supposedly, he gets hipper after an encounter with two acidheads in a painted VW bus (played by Paul Dano and Kelli Garner), but it's too little, too late. The screenplay is by Lee's frequent collaborator James Schamus, adapted from Tiber's memoir, "Taking Woodstock: A True Story of a Riot, a Concert, and a Life," and though Schamus has captured a little bit of the life and a tiny portion of the spirit of the concert, there really is no riot in evidence. Lee's filmmaking is both overly fussed-over and listless. When he splits the screen, you wonder why he's even bothering: Instead of using the effect to put all our senses on alert as we do the extra work of looking in two places at once, he fills each frame with stuff that's hardly worth looking at -- someone's bent elbow here, a half-obscured face there.

Martin doesn't have enough appeal to anchor the film, and Staunton, as his hard-bitten, long-suffering mother, is exhausting to watch. (At one point she glares out through her hard little eyes and offers a self-pitying speech that begins with "I walked here all the way from Minsk" and ends up at "with nothing but cold potatoes in my pockets." I began to laugh at what I believed was an intentionally comical exaggeration, but I wasn't sure I was supposed to -- Lee frames the moment blankly, as if not even he knows what to make of it.)

But Lee does capture a few good performances here: Groff is charming as the almost-bare-chested free spirit Lang, and Liev Schreiber shows up as a big-hearted, plain-talking, cross-dressing bodyguard. Goodman, as Elliot's father, has the best moment: An exhausted, beaten-down man (that Sonia sure is a handful), he blossoms, and even has actual fun, when his land is invaded by so many friendly, open young people. At one point, just as the concert is beginning a few acres away, he and Elliot hear strains of music drifting across the pond on their property (in which a bunch of carefree, long-haired kids are happily skinny-dipping). Jake looks at his dutiful son and urges him to go over to Max's field to hear the music, to be part of something. Goodman fills the moment with just the right amount of emotion, and no more. He's packed three days of peace and music into one glance, which is more than Lee manages to scrape together in more than two hours' worth of film.

Shares