"The main character is a man with no self, no discernible personality. I find myself thinking about this man a great deal, about how marvelous his life must be! He has no future, no past, no responsibilities. He's simple, boring, an absolute plank. People expect nothing from him, and then love it when they get just that." -- Geoffrey Rush as Peter Sellers, discussing Chance from "Being There," in "The Life and Death of Peter Sellers"

The riddle of narcissism is this: While narcissists live for admiration and adoration, while they depend on companionship and hate to be alone, while they can pull others into the grandiose worlds they create with their imaginations, they tend to want to escape all expectations and responsibilities in life, seeking out an external numbness to match the numbness they feel for others.

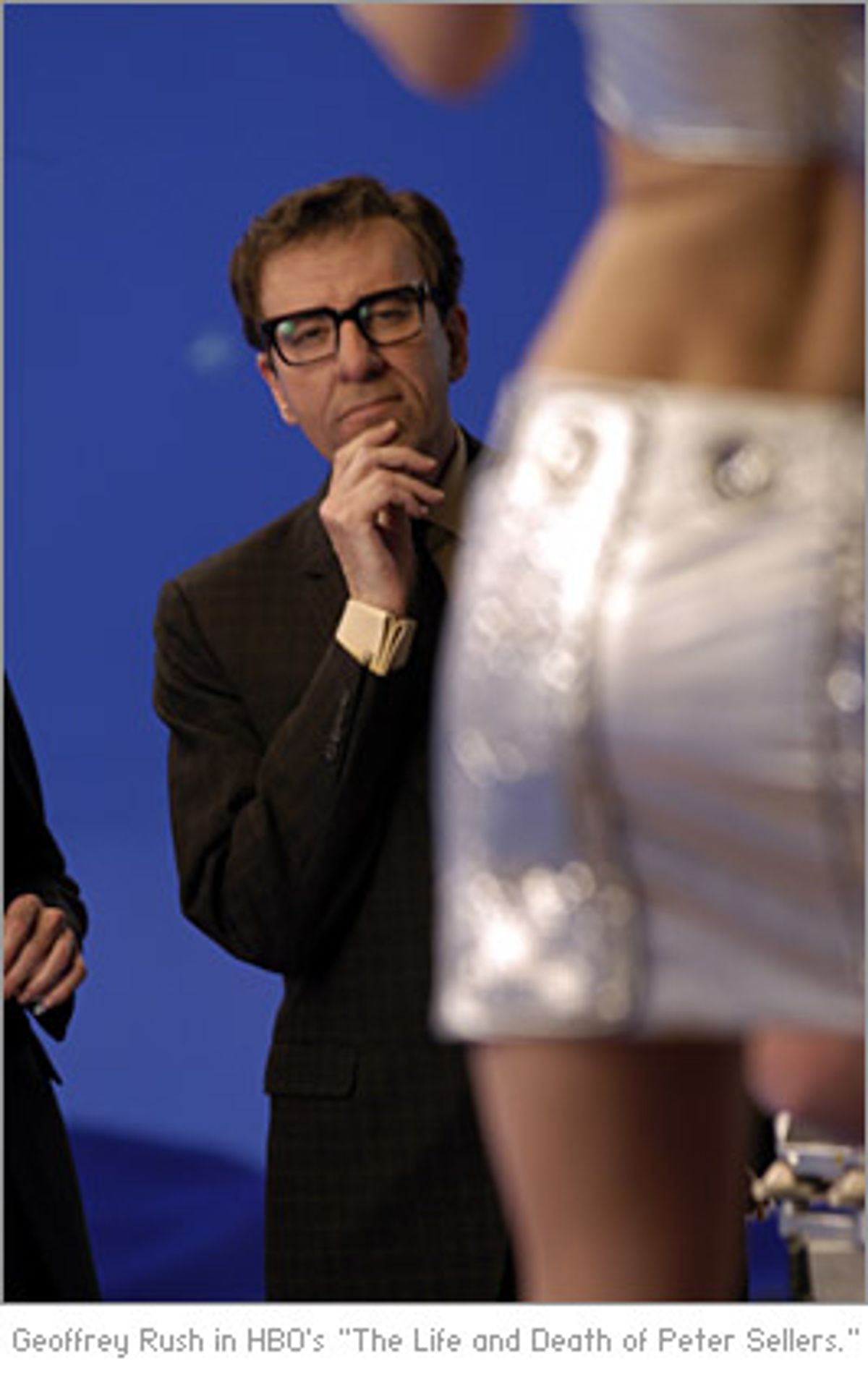

This is the essential conflict director Stephen Hopkins brings to life so brilliantly in "The Life and Death of Peter Sellers" (Sunday at 9 p.m.; HBO). Like many narcissists, Sellers was an intensely charming man, brimming over with mercurial wit and affectionate embellishments and flights of grandiosity, and it's all embodied with agility and grace by Geoffrey Rush. But when his mood sank or the pressure of entertaining endlessly was too much to bear, Sellers' essential emptiness and lack of empathy for others became painfully evident.

The resulting roller-coaster ride is as thrilling as it is horrifying. Without any guiding beliefs or concerns for others, the narcissist is a wildly unpredictable presence, shifting from rapture to despair without warning. Somehow, Hopkins manages to capture this bewildering state without turning Sellers into either a monster or a genius worthy of our unconditional love in spite of every misstep. Hopkins fearlessly takes on the strange lightness and absurdity of even the most disastrously callous moments, an odd mood that's familiar to anyone who's been close to a narcissist. When Sellers discovers that his son has painted a racing stripe on his luxury car, he marches upstairs and smashes his son's train set to bits. Later, when Sellers decides, in a deluded state, that he'll be leaving his wife and children for Sophia Loren, he announces his plans to all three of them. When his daughter asks doesn't he love them anymore, he answers, calmly, that he simply loves Sophia Loren more (his affections, naturally, are not returned). These are the words of a man who has less of a grasp of (or concern for) the feelings of others than a small child.

What this film captures so beautifully is that there's something delightful in this essential disconnect -- even as his wife (a pitch-perfect Emily Watson) leaves him for the interior decorator (after Sellers practically begs her to do so), even as Britt Eklund (a brilliant Charlize Theron) smashes his mother's framed portrait over his head, there's something lovely and giddy about the sadness there. Even as it stings, Sellers' stubborn refusal or inability to get in step with the straight world was achingly apparent, and somehow inspiring. Because his selfishness and utter lack of feeling for others were always front and center, because he had a sociopathic streak a mile wide -- as when he openly insults director Blake Edwards at the premiere of the latest Pink Panther film -- those close to him were forced to accept these weaknesses and work around them as best they could. It seems that everyone dealt with Sellers as if he actually was a small child, and as a reward, they were treated to a richly imaginative world that only could have been created by a child's wild spirit.

Whether or not this appeals to any given person depends largely on how tolerant they are of self-involvement, or how fixated they are on transcending the mundane. For their part, Rush and Hopkins do a masterly job of bringing Sellers' unique universe to life through a series of bizarre flights of fancy in which Rush (as Sellers) plays the character of his mother, or his wife, or his director, echoing the rationalizations for his heartless behavior, or giving voice to the hopelessly high expectations he has of them.

Rarely do such creative indulgences bring so much to a character and a story, but these little digressions are absolutely at home in this story -- in fact, it's impossible to imagine doing justice to Sellers' dizzying, spontaneous inner world without them. While some might complain that the story does little to shed light on the sources of Sellers' pathologies, narcissism is incredibly difficult to trace back to root causes, and really, haven't we seen enough of demonic parental caricatures, stuck in place to account for behaviors that are far too inconsistent and unusual to be summed up neatly? Instead, our experience of Sellers is just as bewitching and as melancholy and as inexplicable as it must've been for those who knew him well. From the lively soundtrack to the eye-catching, beautiful sets to the amazing cast, "The Life and Death of Peter Sellers" expertly and imaginatively captures the joyful, horrible, fantastical world of a unique comic genius who was anything but simple and boring.

Shares