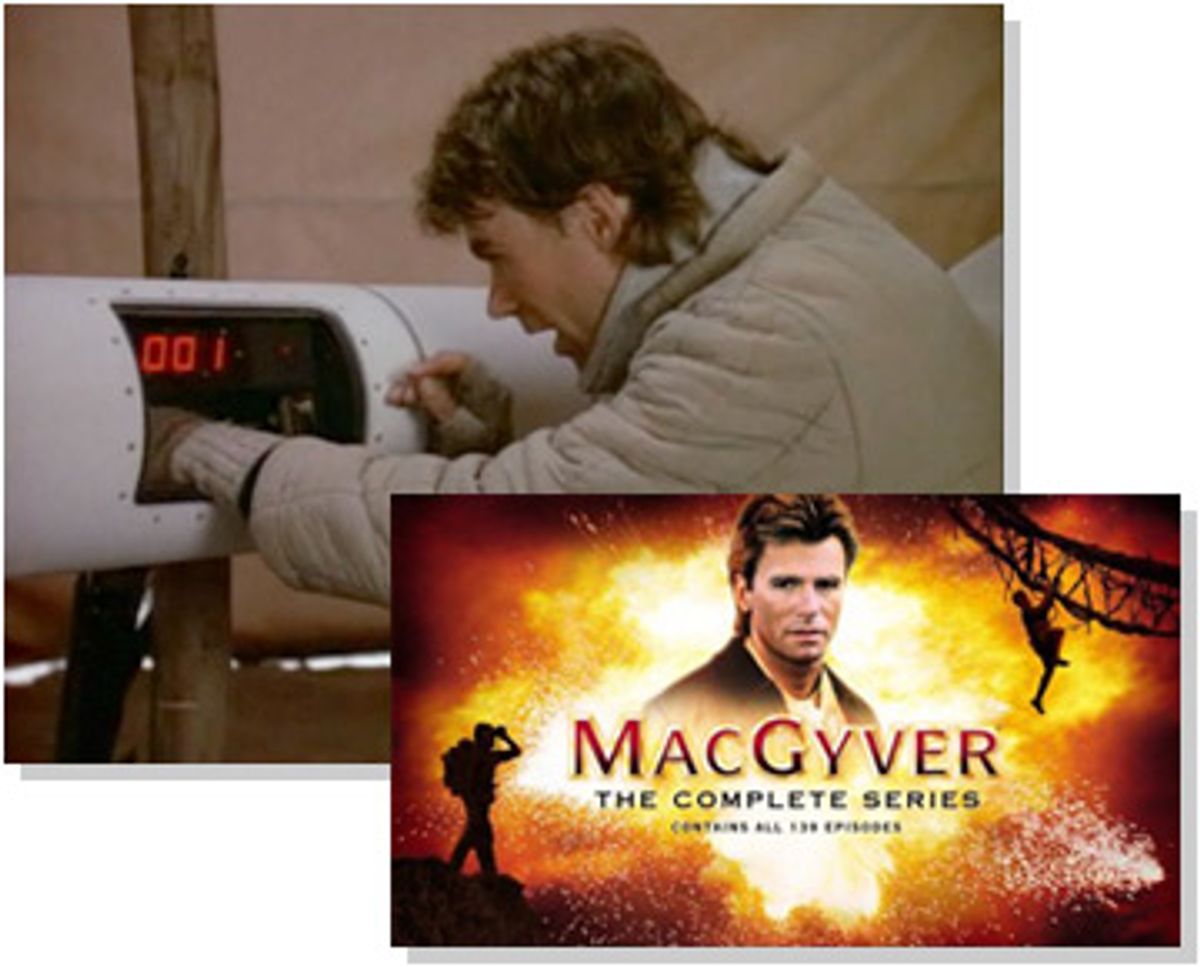

It isn't necessary to explain how, in the pilot episode of "MacGyver," our mulleted, Midwestern hero gets himself trapped inside a top-secret research bunker overflowing with sulfuric acid. Suffice it to say, he needs to find a way out, and probably soon (because government agents are fixing to fire a missile at the bunker to prevent the acid from spilling into a nearby aquifer). Plus, he has to save the people he has found inside (among them a gun-wielding climate scientist who wants destroy the bunker in an effort to set back research into an ozone-layer-ruining weapon of mass destruction). Fortunately, MacGyver has a few chocolate bars, a scrap of sodium metal, a cold capsule, a pair of binoculars and cigarettes.

He uses the chocolate to plug up the leaking tank of acid -- sulfuric acid reacts with sugar to form a kind of glue. The sodium, scraped into the shell of the cold capsule and splashed into a sealed bottle of water, makes for a handy time-delay bomb, which proves useful for blowing through a wall that blocks the group's escape. The smoke from the cigarettes illuminates the bunker's laser-beam security system that he has to get through to move through the bunker (no secret underground research lab is complete without lasers); MacGyver uses the binocular lens to aim the laser at its own control unit, shutting down the security system.

But how does he get out of the bunker? Oh, that's the easy part: MacGyver finds a switch that controls the lights in an above-ground control tower. He flashes the lights on and off to send an SOS message in Morse code. The guys in the tower, realizing Mac's in the bunker, alive, call off the missile -- and for the first of 139 times during the show's seven-year run from 1985 to 1992, MacGyver saves the day.

This first episode is nearly perfect. It neatly telegraphs MacGyver's soul: A laid-back fellow oozing can-do heartland ingenuity, MacGyver is handsome but dorky, charming but self-effacing, a friend to orphans and children with disabilities, tolerant of people from foreign lands, and though he has every opportunity for indiscretion, he's always a gentleman around women. MacGyver, played by the affable Richard Dean Anderson, works as a secret agent for a vaguely defined defense contractor whose intentions are always of the best sort. His gigs are of the usual action-hero variety -- find stolen missiles, escape assassins, rescue civilians, humiliate dictators. But his near chastity, along with his staunch opposition to guns and capacity to solve every problem through the judicious application of chemistry and physics, sets him apart from other action stars. MacGyver is the thinking man's hero.

Though, actually, when you go back to watch his adventures two decades after they first aired, you discover Mac's target audience probably consisted mainly of boys, not men. I started watching the 139-episode DVD boxed set a few weeks ago, shortly after gadget blogs gleefully reported that Lee David Zlotoff, the series' creator, said he was thinking of making a "MacGyver" movie. This jogged in me memories of boyhood, especially of how, after watching each MacGyver trick, I'd feel a bit invincible: I was small, but I was clever. Like MacGyver, I could take them.

But to adult eyes "MacGyver" is often too goofy by half. It's not just that his tricks are improbable. At times -- like when he interprets a deaf friend's dreams to find clues to an impending missile theft -- they seem to violate the show's premise, that science beats brawn. In these instances, MacGyver doesn't use science; he uses magic.

Then there are the children he befriends and the liberal orthodoxies he defends -- tendencies that bump the show's preachiness dial. Mac's always popping up in foreign countries -- Afghanistan, Myanmar -- and running into kids and peasants who are oppressed by unsmiling overlords. In just about every second episode, he's teaching kids about the dangers of guns, a position that, we learn in one episode, he came to as a boy, when a friend of his was killed by a gun. The antigun thing is a little specious, though: MacGyver's got nothing but nothing but love for explosives, painful booby traps, fire extinguishers rigged up as projectiles, and enormous boulders that he sets up to fall on villains. The real reason he doesn't use guns is obvious -- he'd be able to shoot his way out of most traps, and that would be too easy.

I don't mean to get down on "MacGyver." There's something in its flaws worthy of re-viewing, a particular moment in America preserved on TV. MacGyver is meant to exemplify a certain noble strain of American power. He doesn't take the easy way out, and when in a jam, he uses what he finds around him to ingenious effect. If you strain you see a greater American story here too -- that his ingenuity is frequently too good to be true, and leads to pat, uncomplicated endings that call for no greater reflection.

There's also something striking about "MacGyver's" moment in TV. Watch this show as a yardstick to measure how far we've come. Even the simplest dramas today -- I'm looking at you, "CSI" -- are complex and multilayered next to "MacGyver," which underlines and explains everything, gums up all dialogue with exposition and introduces new, throwaway characters in each episode. There's much hand-holding here: Even in foreign countries, everyone speaks English, every villain is one-dimensionally evil, and every tender moment is helped along by a swelling score.

But that's why I hope someone makes a "MacGyver" movie. Mac needs a makeover. Lift him up to big-budget action standards -- give him a story line that can span a couple of hours; give him a girl to love, but who may also cross him; give him a more complex mission (maybe to find out who's putting all the salmonella in our salads?); and give the whole package fast, Paul Greengrass-style editing. Also, make sure one of his crazy solutions involves Mentos -- people online go crazy for tricks with Mentos. Do all that and we might yet have a lasting American hero.

* * * * *

Read more of Salon's Re-Viewed, offering a fresh look at great TV shows available on DVD.

Shares