It's hard not to be impressed, at the end of the show's second season, at "Survivor's'" capacity for surprise. Tina Wesson wasn't a long shot. Under the rules of the game, it was well within the realm of possibility for her to have won the last immunity challenge, dumped her studly buddy Colby and faced off against the dour Keith for an easy million.

But like last year's edition, the way Tina eventually won was unpredictable -- and arresting in its implications.

The final immunity challenge was a fair one -- a mental memory game of trivia about the players' personal lives, not a physical test. It's also a game with humanistic implications: Who had taken the time to learn about his or her fellow survivors?

Tina had a fair chance at this game, and lost. Had Colby been playing for the sake of the money, he would have ejected her and taken his chances with the less likable Keith. He was obviously playing for different reasons, and that's what gave Tina the million.

Last year's moral was similarly cloudy. While everyone wheezed about how Richard Hatch's manipulations won the day (an impression the good corporate consultant himself has assiduously encouraged), Hatch actually wound up first via a series of flukes. His endgame rival, Kelly, won a grim and astonishing series of immunity challenges to keep herself in the game and force herself into the final two.

The argument can be made that against anyone else Hatch would have lost -- and in the event, he picked up his fourth and winning vote when a voter named Greg made his choice randomly.

That takes away nothing from Hatch's victory: It's just to point out that in the insular world of a "Survivor" set, small actions have ripple effects, some of them explosive and some of them beneficent.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Stacey, one of the cast members of the first "Survivor," has sued the show and its producers, saying that they manipulated the voting on the first series, persuading the contestants whom to vote off the island for better dramatic play.

Since the show makes such a big deal out of the contestants' fending for themselves, it'll be disappointing if it comes out that "Survivor" thugs were twisting the arms of the players off-camera to direct the voting.

So maybe some day we'll find that producer Mark Burnett somehow persuaded Colby that an endgame in which the Texas stud faced off against the dulcet Tennessean Tina -- rather than the abrasive Detroiter Keith -- would make for some darn fine television.

Is Burnett a cheater? A few years down the line, a tell-all book may come out, detailing a smorgasbord of indiscretions -- pressures on voters, manipulations of the environment, behind-the-scenes intrigue.

It's not as if Burnett is a stickler for reality. At last night's finale, we saw the show's sleek helicopter racing over Los Angeles on a clear Southern California night. It swooped over the brightly lit rides on the Santa Monica pier, raced over glittery Century City and glided down onto an impromptu "Survivor" helipad next to the CBS studios. Probst got off the helicopter and ran into the stage.

It was a nice dramatic intro for the last scene of the series -- except for the fact that it was 7 p.m. in L.A. at the time, and still light out.

What else did the "Survivor" producers finesse? Maybe the baby pig Michael so conveniently chased down and slaughtered on camera was simply let out of a little bag for his benefit.

Perhaps then producers manipulated the roulette wheel so that vegetarian Kimmi would get the cow's brain to gag on and not the Snickers bar.

Was the rice can really left out in the river wash, where it could be carried away by the flash flood?

We should remember that from a technical standpoint "Survivor" is a remarkable show. The production values are uniformly taken for granted. You only have to spend some time with some of the grimier entries in the genre -- "The Mole," most notably, but also "Chains of Love" -- to see how easy it is to make reality incoherent.

"Survivor" editors have an easy vocabulary that includes everything from brisk and funny cutaways -- here Jerri plotting her mischief, there a snapping turtle in action -- to complex and graceful story arcs that pay off three and four episodes later. The show's peccadilloes -- recycled shots of the same damn crocodile slipping off into the water or kangaroos loping through the forest, when the survivors themselves almost never saw either -- were minor.

But in a way the genius of "Survivor" is that it almost doesn't matter how manipulated the characters are. It's hard to shake the reality TV jones. There's something intriguing about watching the players -- ambitious and conflicted but nonetheless "real" people -- interact. It is perhaps one of "Survivor's" secrets that, in an age in which convenience-store clerks who've slept with their aunts jockey to tell their stories on daytime television, it has a built-in mechanism to factor out posturing.

The contestants are thrown into adversity and immediately weakened by exertion, stress, exposure and lack of food. (In the static and boring "Big Brother" household, by contrast, the contestants never forgot they were on camera.)

The show can be cruel. As we saw in the reunion show that aired after this year's finale, Deb, the contestant briskly dismissed on the first show, found the experience -- demonized, isolated, ejected and then made a pop-culture punchline -- wrenching. Inarticulate and shamed, she didn't even want to even appear on the reunion and could do little but cry.

And we never did find out what made Keith so dislikable. What did he do to people, anyway? Sure, he was a little arrogant at times, maybe proud, but "Survivor" cameras capture contestants doing all sorts of seriously unattractive things and not one ever produced a smoking gun for Keith.

Yet neither seems to have been treated unfairly. Deb's very inability to explain herself spoke volumes, and Keith, well, it seems to be Keith's curse that he comes across as a noodge. He might not like it that his kids see him treated as a pariah on national television, but then he didn't have to try to win a million dollars on a national TV show, did he?

In other words, the show seemed to be capturing something close to, well, reality.

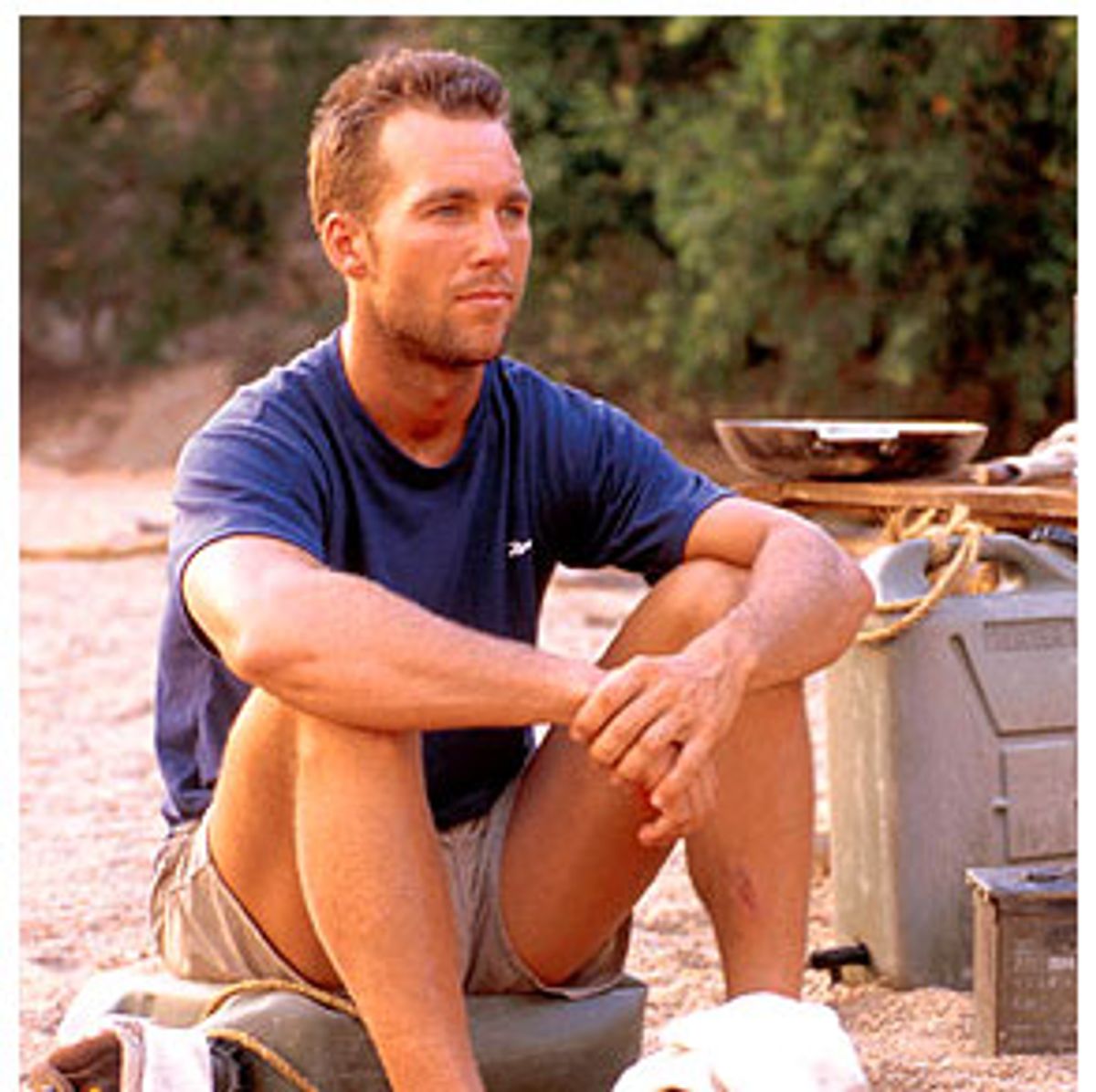

Consider Colby. He made it plain he was there to play to win, as he told us again and again. All of Colby's determination to "play the game" set us up to believe he'd calmly jettison Tina when he had to.

Yet it turned out there were reservoirs of commitment in Colby to a melange of very abstract ideas -- personal worth, karma, cosmic chance -- that, while they caught us off guard, were not inconsistent, in the end, with the man the show had presented us.

While I'm sure that the vaguely differentiated mass of American television sitcoms and dramas I can't bear to watch occasionally touch, sometimes professionally, on themes like these, I doubt they are presented in quite so slicing and, yet, ambiguous, a fashion.

Why, in the end, did Colby jettison Keith? Because he liked Tina better? (A million dollars better?) Because he didn't want to be seen as a person who would jettison a nice person like Tina? (Despite his repeated assertions that he was exactly that kind of a person?)

Because his animosity for Keith ran that deep? Because he'd seen too many Clint Eastwood movies?

Did you watch "Survivor" closely and ridicule his Texas stolidity? Did you hoot at his flirtations with Jerri, until, George W. Bush-like, he got himself back on track and focused on accepting his destiny? And would you have bet cash money he'd apologetically but determinedly leverage Keith as his best chance to win?

Me, too. Colby's no Sydney Carton, and yet in the end he did a far, far better thing than we expected him to do. It says something, in the end, about Colby, and maybe something about the people watching, that we expected the worst from him and yet he couldn't bring himself to give it to us.

Shares