If “Some Like It Hot” isn’t the funniest movie ever made, you can’t blame it for not trying. The first time you see Billy Wilder’s 1959 farce, you might not believe that anything can make you laugh so hard for so long. Where most comedies wear out their audience after an hour and a half, “Some Like It Hot” goes on for 122 minutes and leaves you ebullient.

Years later, the stray memory of a scene or a bit of dialogue can get you chuckling to yourself: Consider the wheezing, open-mouthed laugh of Joe E. Brown, or his delivery of the movie’s capper, the most perfect last line in the history of movies. Or what about the party in the upper berth of that railroad car — even more cramped than the stateroom sequence in “A Night at the Opera” — where an in-drag Jack Lemmon gets happily soused with an all-girl jazz orchestra?

Then there’s Tony Curtis’ affectionate takeoff on Cary Grant; hulking movie heavy Mike Mazurki asking Curtis and Lemmon, “Ain’t I had the pleasure of meeting you two broads before?”; Marilyn Monroe somehow staying in her diaphanous gown while she sings “I Wanna Be Loved By You”; and Curtis and Monroe’s love scene, on a moonlit yacht in the middle of the night, which got the film banned in Kansas City. (One of my best friends has broken me up for years by, without warning, quoting Lemmon’s line, “We wore grass skirts,” and then breaking into Lemmon’s impromptu hula.)

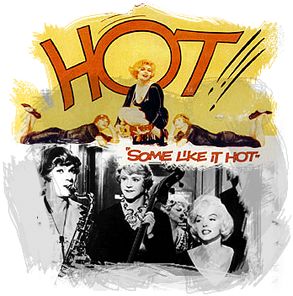

There’s still an amazing appetite for “Some Like It Hot.” It’s been reissued on DVD, in a transfer that preserves Charles Lang’s gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, with a few extra documentaries: reminiscences from Tony Curtis and the actresses who were part of the girl band. And it’s the subject of a lavish $150 coffee-table book from Taschen that includes the entire script (accompanied by numerous stills), interviews with Lemmon, Curtis and Wilder, reproductions of the original advertising art and reviews, and even a facsimile of Monroe’s prompt book (with handwritten notes: “Acting — being private in public to be Brave”). It’s a big, lush treat of a book, and its existence says something about the affection people feel for this movie.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about “Some Like It Hot” is how easily it could have all gone wrong. Billy Wilder was never an especially subtle filmmaker. His comedies both before and after this one tended toward the heavy-handed, even the vulgar. “Some Like It Hot,” from a script he wrote with his frequent collaborator I.A.L. Diamond, is played in broad farce style. The jokes don’t quite jab you in the ribs but neither are they witty little glissades. Pauline Kael, who loved it, wrote that the movie hovers “on the brink of really disastrous double-entendre.” You hear what she means in the dialogue: the oral-sex jokes implicit in Monroe and Curtis’ backchat about the sweet or the fuzzy end of the lollipop, or the mannish pair telling Sweet Sue the orchestra leader that she doesn’t have to worry about them getting involved with men. (“Rough hairy beasts,” an offended Lemmon chimes in, “and they all want just one thing from a girl.”)

You see it in the movie’s advertising slogan, which introduced the stars as “Marilyn Monroe — and her bosom companions.” There is also one visual double-entendre, a taunt to the censors that to this day I can’t believe Wilder got away with. The gown Monroe wears to perform with the band is a barely-there number of sheer nylon netting that clearly shows her breasts, the nipples just covered by small cascades of sequins. As she boop-boop-be-doops her way through “I Wanna Be Loved By You,” Wilder puts a tight spotlight on her face and shoulders. When she gets to the line “I couldn’t aspire/To any-thing higher” she wiggles slowly up so that the tips of her breasts stay teasingly just below the spot.

And then there are the winks at the audience. Lemmon is telling Curtis, aping the latter’s Cary Grant routine, “No-body talks like that!” when Pat O’Brien and George Raft turn up as, respectively, a Chicago cop and a bootlegger, parodying the roles they’d played in so many other movies. Observing a slick young mobster doing the coin-flipping routine Raft perfected, Raft asks, “Where’d you learn that cheap trick?”

But somehow these bits tickle you instead of making you groan. “Some Like It Hot” is naughty, all right, but it’s never coarse. Part of the fun is watching the movie parody a then not-so-distant past that had already become iconic lore. Set in Chicago and Florida during Prohibition, the movie is full of gun-toting bootleggers, cops giving chase in Black Marias that seem to turn corners on two wheels, girls in flapper get-ups, millionaires whose life is one extended toot. (Joe E. Brown’s yacht is called the New Caledonia. “The Old Caledonia,” he explains, “went down during a wild party off Cape Hatteras.”)

Curtis and Lemmon play Joe and Jerry, two perpetually down-on-their-luck musicians who accidentally witness the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, the spectacular Chicago Mob hit of 1929. Fleeing for their lives, they don drag and get a job with Sweet Sue and Her Society Syncopators, an all-girl jazz orchestra heading for two weeks in Miami. Lemmon’s Jerry is pop-eyed at the “talent” that surrounds him. It all reminds him of a recurring childhood dream of being locked overnight in a pastry shop with “jelly rolls and mocha éclairs and sponge cake and Boston cream pie and cherry tarts” (another of those double-entendres). Curtis warns him, “We’re on a diet!”

But when they get to Florida, the roles are reversed. It’s Lemmon who blooms in his new identity and Joe who risks it all by impersonating an oil millionaire to woo Sugar Kane (Monroe), the band’s singer. It’s also not too long before the gangsters chasing them turn up at the hotel, attending a convention for — you should pardon the expression — “Friends of Italian Opera” (or, as the hoods themselves like to say, “Eye-talian Opera”).

Years ago, I ran across a comment by a feminist film critic who said that “Some Like It Hot” depicted a male world so predatory that the heroes were literally forced to abandon their sexual identities in order to survive. There’s something to it. This comedy of sexual role confusion is, deep down, a joke on the male desire for security, the fantasy of abandoning yourself to the protected and pampered place of women.

That’s all visible in Jack Lemmon’s performance, perhaps the finest work he ever did. Lemmon doesn’t so much play the role as it plays him. He transcends the obvious joke (one that would have soon worn thin) of how ungainly he and Curtis look in drag and completely surrenders to the woman within. You see something of that in Dustin Hoffman’s performance in “Tootsie” (the movie’s most obvious offspring) and in Michel Serrault’s performance in “La Cage aux Folles.” But I think Lemmon goes even further. He enters that state of comic logic where madness and delusion seem like the most reasonable thing in the world. Wilder brought in a German drag artist to work with Curtis and Lemmon. The guy left after one day in disgust. Curtis was OK, he said, but Lemmon was hopeless. In an interview in the “Some Like It Hot” book, Lemmon says he didn’t want to turn the role into gay shtick. And he doesn’t. He goes for something much farther out and riskier — utter immersion in the feminine.

When he first enters in drag, all he can do is complain about how drafty his dress is and how tough it is to walk in heels. By the end of the movie he’s so comfortable in heels that he wears them without thinking, giving himself away. But his transition starts long before then. Jerry introduces himself as “Daphne,” instead of the agreed-upon “Geraldine.” And there’s a crestfallen look on his face when Sugar tells him that she envies him being “so flat-chested.”

But Jerry’s transformation really comes out in his scenes with the incomparable Joe E. Brown (who, like Harpo Marx, can seem like one of God’s crazed angels) as Osgood Fielding III. Osgood is a lecherous old millionaire who’s been married to so many showgirls he can’t keep track (luckily, his ma-maw does). To help Joe in his seduction of Sugar, Jerry agrees, under much protest, to a date with Osgood. The two of them tango till dawn and Jerry returns, still shaking his maracas, and announces without a trace of irony, “I’m engaged.” When an incredulous Joe asks him, “Why would a guy want to marry a guy?” Jerry answers, as if it’s the most obvious thing in the world, “Security.”

It makes sense. Jerry’s the practical one of the duo. When the movie opens, he’s planning to use his paycheck to pay a little something to everyone he owes, to get to the dentist to get a bad tooth taken care of. But he lets Joe talk him into hocking their overcoats (in a Chicago February!) to put the money on a “sure thing” at the dog track. He’s sick of not eating, of not knowing where the next job will come from, of running for his life. He looks at the way women are taken care of, protected, fawned over — even the girls in the band, watched like hawks by Sweet Sue and her manager, Beinstock — and feels envious.

At last! An end to all his troubles. Plenty of money, plenty of clothes, and three squares! And if all it takes is the occasional night of tangoing or a pinched ass in the elevator, well, he can live with that. To be a man in “Some Like It Hot” means to be either a killer or on the run from one. So a touch of cuckoo nirvana hovers around Lemmon’s fantasies of married bliss. He’s so far gone into his dream of fussed-over ease that all he can see in Joe’s objections is his best friend ruining what may be his last chance to marry a millionaire.

Envisioning the honeymoon, he says, “He wants to go to the Riviera — but I sort of lean toward Niagara Falls.” And when Joe asks him if his engagement present, a diamond bracelet, is the real thing, he answers huffily, “Naturally. You think my fiancé is a bum?” Not that he expects it all to work out. “I’ll tell him the truth when the time comes,” Joe promises. “Then we’ll get a quick annulment — he’ll make a nice settlement on me — and I’ll have those alimony checks coming in ehhvv-ery month!”

Not everyone in the movie is lucky enough to be so deluded. Neither Joe, who’s after Sugar the first chance he gets, nor Sugar, who keeps falling for tenor sax players, the type who leave her with no more than “a pair of old socks and a tube of toothpaste, all squeezed out,” can be anything other than what they are. (In fact, Joe is the exact sort of heel Sugar is running away from. And the means he uses to get her — fulfilling her fantasy of the sensitive, bespectacled millionaire — are trickery.) Like romantic comedy, which it is not, “Some Like It Hot” envisions sexual attraction as chaos, an adventure, perhaps a compulsion, but not as a promise of happiness. Joe and Sugar, who each know which end of the lollipop they like, are stuck in their sexual roles, and ready to take their respective lumps all over again.

There’s a shot that rather elegantly sums up the movie’s sexual topsy-turviness. Sugar, on the bandstand, believing her millionaire has shipped out to South America to marry the daughter of a Venezuelan oil tycoon, is pouring her heart out in “I’m Through With Love.” Joe, dressed up as Josephine and about to make his final getaway, watches from the sidelines. He walks on stage right up to her, brushes away her tears, and — using his real voice, the first time she has heard it — tells her, “None of that, Sugar. No guy is worth it.” It’s Joe’s admission that he’s been a heel, and his wish that he could do better. But the great moment follows, as he takes her in his arms and kisses her. Sugar responds not with her head but with her heart, melting into the kiss and then realizing who this man is that almost got away.

It’s the vision of Monroe and Curtis in drag, locked in that kiss, maybe the only sexual exchange in the picture where both partners are being honest with each other, that stands for the movie’s world of crazy possibility. “Some Like It Hot” does exactly what a farce is supposed to do — it gives you the sense of the world careening pleasurably but unstoppably out of control. Neither Wilder nor Monroe nor Curtis nor Lemmon ever equaled the work they did here. But nobody’s perfect.