I guess it’s only fitting that a larger debate over the advertising-content balance has been inadvertently initiated by contract negotiations over AMC’s “Mad Men” — a show about the early struggles to create and maximize that very balance. At the center of the spat between AMC suits and “Mad Men” creator Matthew Weiner was the execs’ demand that the series be cut by at least two minutes per show so that more ads could air. Ultimately, Weiner largely agreed to AMC’s demands to shave off time from most episodes.

During the brouhaha, AdAge insisted that the program “needs to embrace more advertising, not shun it” because “Mad Men” (supposedly) doesn’t generate enough revenue. Time’s James Poniewozik countered that “it will do no one any good to compromise the show that made the channel’s brand for quality overnight.”

I lean toward Poniewozik’s camp, both for the reason he cites and for the deeper issue at hand — namely, the need to reimagine the advertising-versus-content paradigm in the 21st century.

The Web, email, podcasts and streamable/rippable online video combines a new search-and-aggregation culture with sheer infiniteness. Couple that with the now-ubiquitous use of DVR, and content has not only been disaggregated from its branded source, but also has had its old bonds to advertising severely weakened. Keep throwing circumventable ads at the audience, and they’ll just keep fast forwarding or clicking past them. Make ads technologically unavoidable, and the audience will likely go somewhere else because content consumers surfing the infinite Internet are no longer physically captive to a confined set of old-media conduits — they can and will find compelling content that has fewer ads.

Considering all that, unless media outlets are fusing unavoidable ads to truly unique products, those outlets will likely suffer if they stick to the old advertising-content formulas.

You can certainly argue that “Mad Men” is unique — but it’s also (for now) DVR-able and Netflix-able, meaning many of its viewers are already speeding past the ads. The two minutes of commercials AMC extracted from Weiner just means those viewers will see a slightly abbreviated show rather than more ad spots. Two minutes may not make much of a difference today, but two minutes may become more in the next contract go-around, which could negatively affect viewer experience and, ultimately decrease overall viewership.

This is the same potential slippery slope for all content these days. Newspapers are nearly all online, making display ads avoidable by the reader. Meanwhile, radio’s inherent advantage — the fact that it’s built into every automobile — also makes it susceptible to channel flipping during ad breaks (which explains at least some of the reason why the less-ad-laden NPR has generated big ratings in competition with commercial stations).

Seeing that we’ve clearly arrived at a similar moment of revolutionary media transition as portrayed in “Mad Men,” the question is: What ideas are today’s Don Drapers pursuing to face down the new ads-versus-content challenge that the “Mad Men” spat centers on?

One is to maximize underutilized spaces that can’t be avoided by the audience, but in a way that doesn’t compel consumers to pick up and leave. Two early video-based examples of this are the 15-second ads at the beginning of some embedded YouTube content and the 30-second ads you have to watch in order to access free Wi-Fi in airports. Newspapers are also experimenting with this model by displaying short ads when you click a link to a story. And this week, books jumped into the fray when Amazon announced a discount Kindle whose comparatively low price is financed, in part, by selling ads that appear on the device’s screen saver.

Another model is subscription, which substitutes user fees for ad revenue. That’s the Wall Street Journal/New York Times pay wall, XM/Sirius, independent podcasts, Netflix and iTunes. The former three are having trouble, in part, because much of their content remains similar to what other free outlets are offering. The latter three, on the other hand, are proving viable because much of their programming is, indeed, unique and not replicable.

Still another model is paid product placement and licensing. This poses obvious objectivity problems for news content, but for explicitly entertainment content, these issues are somewhat less problematic, and this model is likely to become more prevalent. That may mean clumsy “Truman Show”-like mugs to camera or nakedly commercial sales pitches like the one parodied in “Wayne’s World.” But it also may mean reverse engineering the process — instead of selling embedded products in the content itself, the content’s brand may be used to sell products in other media. We’re talking about even more of what we saw when “Mad Men” teamed up with Banana Republic on a clothing line (an idea first pioneered by a “thirtysomething’s” fashion catalog).

The ethical concerns here are the same ones raised by the 1980s deregulation of children’s programming by the Reagan FCC, which created a genre of cartoons known as “Program Length Commercials” — television shows directly created by makers of products rather than by studios (think: Toymaker Hasbro directly producing the G.I. Joe cartoons). In this advertising model, content is designed exclusively by and for sales of products, making content one big subliminal commercial.

Of course, lots of viewers would argue that so much content already feels like that, raising the question Reagan’s FCC posed: Is there any difference between a studio-made show later having its characters licensed as toys, as opposed to a toymaker creating a show deliberately to publicize its toys? Well, yes — it’s called transparency. When watching a program-length commercial, the viewer doesn’t necessarily know the creators of the content have only specific product sales (rather than general ratings) in mind.

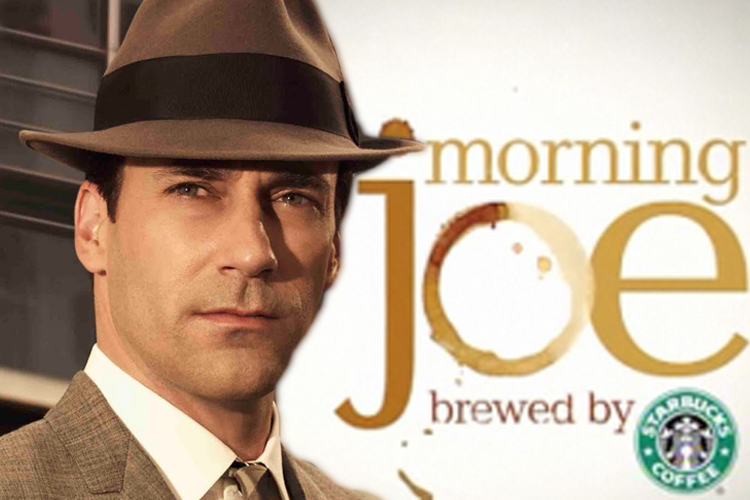

This is why the “Morning Joe’s” model may be the smartest possible solution.

The MSNBC program has a title sponsorship from Starbucks. That’s right, the coffee company pays to have its brand directly embedded in the show’s logo, imaging and graphics. Though this has been controversial, it really shouldn’t be. It’s totally transparent, and journalism-ethics-wise, it’s certainly no more compromising than news programs’ traditional method of stopping every eight minutes for an ad block. Indeed, it may be more honest.

“Morning Joe,” after all, is openly admitting that its programming is being underwritten by a particular sponsor. By contrast, the explicit break from a “Meet the Press” show to an Archer Daniels Midland ad, or the explicit break from NPR programming to a spot about one of NPR’s corporate sponsors suggests some sort of wall between NBC News and ADM and/or NPR and their corporate sponsors — when no such wall really exists, or at least no more of a wall than the one that exists between “Morning Joe” and Starbucks.

The question is whether there are enough advertisers who can or will pay for title sponsorships. Can other television shows find other deep-pocketed companies like Starbucks to replicate the “Morning Joe” model? Can, say, newspapers and magazines find title sponsors to pay for a day’s worth of content? Can commercial radio stations find sole sponsors for whole hours of a program? It’s hard to say — but if a genius like Don Draper were around today, these are precisely the questions he would be asking as more and more 21st century content competitors find ways to reduce commercials and maximize content to build an audience.