The 5- and 6-year-old children in Jane Katch’s mixed kindergarten and first-grade class have invented a game they call “suicide”: One child sits in the suicide seat. Another child offers the first child an apple. He accepts the apple, saying, “Goo, goo. An apple.”

“It’s really a hand grenade,” says the second child. “Do you know you’re going to explode? It’s gonna kill you!”

“I’m going to commit suicide myself,” says the first child, who then pretends to explode and die, while all the other children playing the game laugh.

Katch finds the game disturbing, but she doesn’t prohibit the children from playing it. Instead, she encourages the children to set their own rules for violent play and carry on. In her classroom, Katch tells us in her book, “Under Deadman’s Skin: Discovering the Meaning of Children’s Violent Play,” these rules include: “No excessive blood, no cutting off of body parts, and no blood spilled.” Also, the game cannot include what the children call “mushy stuff.” Says Katch, “The people in their stories cannot take off their clothes. Animals can.”

A teacher for more than 20 years who studied with Bruno Bettelheim at the Orthographic School, Katch decided that it was more important to understand children’s violence than it was to censor it. And for over a year, that is what she did, keeping records and transcripts of her conversations with the children she taught at a small private school in central Massachusetts.

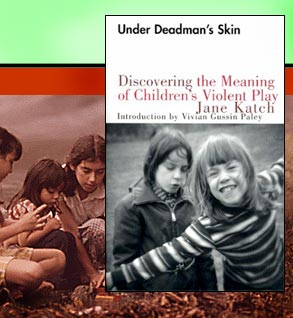

“Under Deadman’s Skin” offers a close examination of the daily interactions of the young children in Katch’s care, told through careful observation, most often in the children’s own words. As a book, it is compelling for its spare prose and sensitive dialogue with children. As a social document, it acts as a map for all those people — teachers, parents and politicians — who would like to understand why children do the things they do.

Katch spoke with Salon about the importance of allowing children to explore their fantasy lives.

In the first line of your book, you mention a game called “suicide,” and you say, “I have never seen a game that I hate so much in which all the children involved are so happy.” How did you first to decide to allow the kids in your class to participate in what seems to be violent play?

In the beginning, I didn’t decide to allow it. It just happened. When I tried to prohibit it, it didn’t work. They just became more sneaky about it, playing when they thought I wasn’t listening. Then I realized that it must be very important to them.

What did the children find so compelling about the game that they were unable to stop playing it?

I think that children generally are bombarded with violence in the media — not only in television and movies that they actually see but also in advertisements for violent movies during television shows and movies that are appropriate. They are also exposed to violence in the advertising that they see on the streets, and by listening to other kids, maybe older kids, talk about movies they’ve seen or heard about. So it’s all around them.

Many people, when confronted with children’s violent play, especially post-Columbine, believe that it is a dress rehearsal for the real thing. At one point in your book, you quote Bettelheim as saying that playing with guns won’t make a child a killer any more than playing with blocks will make him an architect. Do you feel that there is too much emphasis on the symbols of violence?

I think it’s very important for us to limit the violence our children are exposed to, especially for the younger ones. But since they will be exposed to some violence, it’s important to understand that their playing it is the equivalent of adults conversing about it.

For instance, the day after the Columbine shooting, all the teachers were talking about what it must have felt like to be there — to be a parent or a teacher or a student. If our principal had come in saying, “Anyone who is talking about Columbine is in danger of becoming a Columbine shooter,” it would have been detrimental to our well-being. We needed to talk about those things to process them.

Children process things through their play: One child stands up and another child points a finger and says “Bang, bang,” and the first child falls down and then laughs and gets up. That is the child asking: What would it feel like to have been there? What did those children feel like? What would those mothers (whom they saw on the television screen) feel like? We do that through conversation; they do that through play. Could this really happen here? Play is their way to ask that question.

So if we focus on the violence of the content [of their play], we might lose the opportunity to focus on what they are worried about. That’s not to say that we should ignore the violent content — we need to focus on it in a productive way, rather than make them feel bad for even thinking about it.

Many public schools have censored children for engaging in the type of play you allow in your classroom — anything from a 5-year-old who plays finger gun games to a 14-year-old who writes a Halloween essay with violent content can lead to suspension or even expulsion. How much of your freedom came from the fact that you were teaching in a private school?

There are fewer and fewer schools in which teachers are free to experiment in the way that I did, and I feel very fortunate that I was able to do that. I could learn more about the issues involved, and try to come up with new solutions to them. In schools today, there isn’t time, because of the pressure to cover a certain curriculum, and the rules are very strict and limiting about how you can deal with various problems as they come up.

Is this kind of play new? After all, your book opens with a picture of you as a child in a cowgirl outfit, with your hand on a toy gun in a holster. Does this generation of children play differently — are they more influenced by violence than previous generations?

Children’s play often has violent content. Certainly it did when I was a kid and we played cowboys and Indians, or Peter Pan and the pirates. But although it’s normal for kids to be dealing with violent imagery in their play, it’s a lot more explicit today.

So you decided to make rules about the violent play. How did you come up with the first set of rules specifically dealing with violent play?

The children dictate stories to me in the morning, which we then act out later in the day. Sometimes they would dictate stories that, to me, seemed to be inappropriate. I wondered if enacting these stories would make some children feel uncomfortable. So I brought it up in class, and the children made these rules, which I was glad about, because they were close to the rules I had hoped they would make. They decided that the play could not be too bloody, parts of bodies could not be cut off in “pretend” and nothing inside the body could come out. Knowing that some children were made uncomfortable by these things made it easy to set the limits for the kids when they were telling stories.

The fact that these things were happening at all, and that the activities of one child might make another child uncomfortable, implies that there are very different levels of violent play from child to child. Do you have any theories about what causes one child to be more violent than another?

When I talked with the kids about it, one boy said, “The reason I’m not violent is that my parents just say ‘no, no, no, no.'” And yet for another child who isn’t particularly interested in violence, the parents may not have such strict rules at all. It didn’t seem consistent to me. It seems harder for children when their parents’ rules are inconsistent. They would be critical if their parents said, “You can see this movie, but you must cover your eyes at this part because it’s too scary or violent.” They really wanted their parents to be consistent with the rules.

But I didn’t see that kids who were allowed to see more violence played more violently. There were kids who weren’t allowed to see much violence who were so fascinated by it that they would catch every word that other kids were saying, and act as though they had seen the movies themselves, because violence was so attractive to them.

One boy in your classroom, Seth, seemed to embellish the explicitly violent fantasies, and claimed to have seen all of these violent movies. And yet, in talking with him, you eventually discovered that the plot lines he claimed to have seen in violent movies weren’t real. Do you think that for him, and children like him, violence will always be a crucial part of their play, whether or not they are exposed to it in the media?

He was looking for excitement and he would have found it in whatever form it existed in his culture. I’m sure that if there weren’t children seeing these movies in his presence, he would have looked for whatever the exciting thing was in the environment. Some children just seem to be searching for that excitement — but what they find when searching depends upon what they were exposed to.

Eventually, you came to feel strongly enough about this connection between the kids’ violence and the media that you sent a letter home to parents, along with a full bibliography of studies done on violence in the media, and suggested that the parents limit their children’s exposure to violent TV and R-rated movies. Why did you find it necessary to do this?

Parents can find it overwhelming to limit their children’s exposure to violence in the media. Knowing that everyone was limiting it together made it more manageable. They knew that other children in the class wouldn’t be watching those movies and putting pressure on one another to watch more. They knew that if their child went over to somebody else’s home, they probably wouldn’t be seeing something that they had banned in their home. They knew that if their child went to a birthday party, they wouldn’t go out to a violent movie.

What were some of the positive things that came out of allowing children to engage in violent fantasy play?

The most important thing was that they began to listen to each other when they encountered problems in the game. They had to hear the similarities between their feelings about the play, and the differences, and then they had to come to some compromise about their differences of opinion.

They played, for instance, a game they called the “shooting game,” where they pointed with their fingers and said “Bang,” and the person who was pretending to be shot was supposed to fall down. They were getting into a lot of arguments and calling each other cheaters. The game would end with everybody angry, and they would come into the classroom upset after recess.

It turned out that the biggest problem was that when a child pretended to shoot another child, the child who was supposedly shot would refuse to fall down, saying, “You didn’t really get me.” That’s when the arguments began. So they made a rule that if you pointed a finger at someone and said “Bang,” the other child had to fall down, but could count to 10 and get up again. The child who was “shot” at wasn’t out of the game for too long, so he felt satisfied, and the person who did the pretend shooting felt satisfied because it had the desired effect.

After that, they could play in a way that was actually peaceful in spite of the violent content, which to me is a really important distinction. There is play that has violence in the fantasy content — like cowboys and Indians did, or Peter Pan when he gets the pirates, or the pretend suicide. That’s all imaginary violence. And then there is real violence when children are actually angry at each other and hurtful, either physically or emotionally. As the children negotiated the rules, they became more peaceful with each other in reality.

So you believe that the rules are more important than the content?

Violent content can make children anxious; it can make them uncomfortable. So we tried to limit it. And that involves listening to each other and understanding that people have different tolerance levels.

For example, it often comes up in a classroom that some children like to be touched and other children like a lot of privacy around physical issues. A child will reach out and spontaneously touch a friend, and the other child will like it or not, depending upon how they feel about their own body. A child who doesn’t like it might feel that the touch was aggressive, even if it was meant in a friendly way.

Understanding those differences helps children connect with each other more positively. The same thing is true of how they feel about violence. A child can enjoy a pretend shooting game or can feel attacked by it. If they feel attacked by it, you can’t play it with them.

Let’s talk a bit about the way democratic principles work in your classroom. In one case, you raised issues in a classroom meeting about the way violent play was being handled on the playground, and the children more or less vetoed some of your ideas in favor of their own. How, as a teacher, do you negotiate democratic rules without letting go of your authority?

I make all the rules that have to do with physical or emotional safety. The children know that I am responsible for that, and they accept that. The rules that we negotiate are those in which they really can’t make a bad choice. I might not agree with them, I might think that another decision would have been better or I might not have thought of their ideas. Most of the time, the latter was true. I never would have imagined their solutions. But we’d try them, and if they worked we would keep those rules, and if they didn’t we’d come back and negotiate them again.

My rules included things like: “You can’t touch when you pretend to fight” — they could do things like pretend to shoot each other with a finger, but they couldn’t come close enough to do physical harm. And you can’t say, “You can’t play,” which is a rule that protects children from being excluded.

Why do you think it’s important to allow children to have some say in creating rules for themselves?

First of all, I think the rules are very effective when the children make them. Second of all, it gives children the message that listening to each other is important — that’s good both for the children who are speaking and for those who are listening.

We didn’t usually vote about our rules; we usually used the consensus model, which is much harder. It means that you really have to listen to everyone and figure out how best to accommodate their needs.

In the beginning, it takes a lot of time. We would come back to some issues two or three times before we would resolve them. But as time went on, they were doing it themselves: They’d come in from recess and report to me about issues that they’d solved at recess. And then it got to the point where they didn’t even bother telling me, because they were just so used to doing it. Parents told me that they would hear the children negotiating at home with their siblings or their friends.

We adults are not always there to help children negotiate these things. It’s more valuable to give them the tools — so that they know how to negotiate issues themselves — than the rules, which they won’t necessarily be using when they are not with us.

When you began your research on children’s play, you tried to focus exclusively on issues of violence. But when you reviewed the tapes of the children speaking, you found that they were continually talking about issues of exclusion. At first, you cut out those parts of the tape. What made you decide that violence and exclusion were closely linked?

It seemed as though the exclusion led to violence — in two different ways. First, the excluded child felt entitled to get revenge. Second, the children doing the excluding felt entitled to be violent toward the excluded child because that child had been labeled as being different. One boy remembered being called a girl and then hit. Another boy said he was called a baby and then pushed down. So it seemed that just the fact of being excluded, of being considered different from the others, was enough to make them feel entitled to be hurtful.

What were some of the gender differences you saw in children’s play?

The boys were much more attracted to the violence than the girls. There was only one girl who really enjoyed the games that had violent fantasies in them. And when she played, she always wanted to make sure that everyone in the game was OK. She was quick to make compromises and to look out for other people. It also seemed to me as though the girls were more curious about everybody’s feelings. A girl watching boys play a battleship game would say, “Why do they like violence so much?” I didn’t hear boys asking those kinds of questions.

But girls could be very mean to each other — and very exclusionary. Their meanness was more quiet. I had to look very carefully to even see it. A girl would say to everyone in the group how much she liked a thing that they were wearing, but leave one girl out. And everyone knew that she would always leave the same girl out.

So compliments as warfare?

Exactly. Girls’ cruelty is much more subtle, even at 5 and 6. It’s hard to criticize someone for not complimenting someone. But she knew exactly what she was doing, because as soon as she saw I was watching, she complimented the last girl.

I wonder how much of that has to do with the fear of getting in trouble. Boys have a positive model of the “bad” boy, whereas there doesn’t seem to be an equivalent “bad” girl role for girls.

That’s true. They can be bad babies. There is always a girl who loves to be a bad baby, and a girl who likes to be the bad baby’s mother and spank her as much as possible. Real spanking isn’t allowed, of course.

You mentioned that other teachers seemed to believe that boys’ pretend gunplay was more serious than girls who would spank their dolls.

I suspect that, as women, we are more comfortable with girls’ subtle aggression than we are with boys’ active aggression. I’ve noticed that some male teachers don’t have quite the same reactions to violent play — not that they like the kids being outwardly aggressive toward one another, but I think they are more at home with it. It’s not as disturbing to them.

At one point, one mother tells you that she is concerned about the language her daughter is using, and that she sent her daughter to a private school so that she would be around “nice” kids, not bad kids. Did you encounter resistance from parents? Did some of them believe that violent play and explicit language had no place in a “nice” child’s life?

Almost every class has a child that children and parents label the “bad boy” or “bad girl.” I believe the children find it fascinating to watch and talk about a child who tries to do all the things they would like to do but don’t dare try. One child told me, “At dinner my brother told my dad, who’s a doctor, that he fell off the top of the climber, so I told them the bad things Susie did in school, and my dad said I can’t go to her birthday party, but she’s my friend and I want to go to her party.”

Often the parents complain to me during conferences about this exciting child, and I believe my job is to show them that it is in their child’s best interests to learn how to deal with the wide range of personalities found within the normal range of schoolchildren, rather than to be so protected that they will not know what to do when they meet someone who is different than they are.

I do think that explaining clearly to the parents what I am doing and how their children will benefit is important, especially since what I am doing is unusual.

Jason, the 10-year-old, tells you that he has now reached a point where he knows the line between make-believe and reality, and he says of his father, “He knows I know he knows.” At this point, Jason makes an argument for self-regulation of his own TV and video-game watching. Is there such an age? And if so, when is it? How does a parent know that their child knows?

Actually, he was very respectful of his parents’ discussions with him about violence and of the rules they had made about his violent video games, which he loved. He respected their requirement that the game be mostly about interaction or skill or something other than violence, though it could have violence in it. They didn’t want him playing games where all you did was kill. He understood that.

Jason also said, after Columbine, that he was much more concerned about the violent video games he played than he had been before. And he thought maybe his parents should prohibit him from playing them, although he knew he would be very angry for several months if they made that rule. The important thing about Jason and his violent games was the way that he talked about them with his father. That relationship was important to him, and his father understood his interest, but Jason understood his father’s concern.

Jason is a good example of how a child can have an interest in violence but not be a violent human being. He was a very caring boy who thought a lot about the feelings of other children. It’s hard to say what’s right for everybody. It really does depend on the child. If he was a child who did nothing but play violent video games, and didn’t have any friends and didn’t talk to his parents, he would have a very different overall picture, and I would be a lot more worried about that child than I was about Jason.

Jason makes the distinction between “purposeful” violence — such as that in “Amistad,” which comes with social content — and “senseless” or “gratuitous” violence, such as the kind seen in, say, “Anaconda.” Is there such a distinction?

Certainly, at his age, he was able to distinguish between movies that were violent just for excitement and stimulation and movies that had a deeper meaning, which he felt “Amistad” had. I don’t know that the 5- and 6-year-olds would be able to make that distinction, because they wouldn’t be able to tell what was real and what was not real. They wouldn’t be able to tell if, say, “Amistad” was a violent fantasy or a historical fiction.

What do you believe is the ultimate effect on children who are punished for their violent fantasies?

First of all, I think they believe they are bad to have them at all. And that’s a terrible position for them to be in, because they can’t stop their fantasies. If anything, they are likely to have them more intensely after they have been punished. They’re not likely to have fewer violent fantasies after being punished. So it can trigger a vicious cycle of negative feelings.

It’s also a lost opportunity — they are not going to be very willing, even if someone asks them, to talk about their fears and their worries, because they’ve found that it’s dangerous to do so. So getting them help may become even harder.

But it depends upon what the rest of the picture looks like. If the 14-year-old writing the story also is surly with teachers, doesn’t have a good relationship with his parents, doesn’t have friends and seems to be obsessed with violent fantasies, that is a very different picture of a child than one who seems to be getting along well with people and writes one violent story.

If a parent is concerned about a child’s violent play, then it would be good to talk to somebody about that. As parents, we know our children, and if they are playing in a way that’s new and disturbing, we should trust ourselves and act on that. We should talk to someone — it could be a teacher we know very well, or a pediatrician or health professional. But I think we should trust that worry and that knowing that something is wrong and get the help we need.