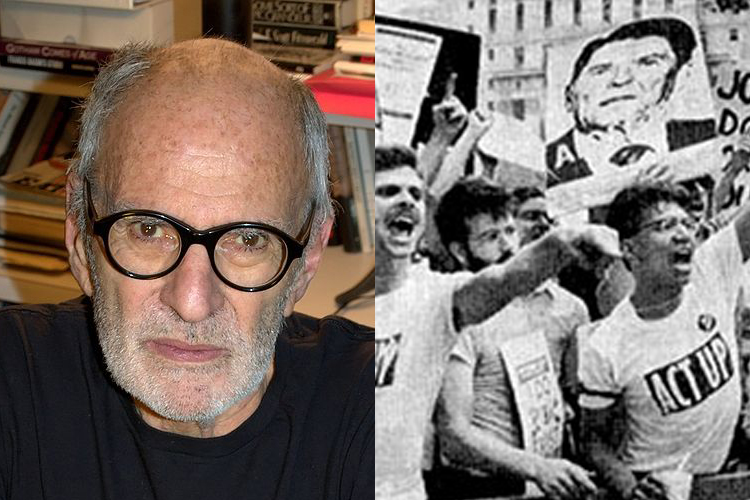

To say Larry Kramer is polarizing is like saying Rush Limbaugh is a little bit conservative. The Pulitzer-nominated playwright, screenwriter, author and activist has been one of the most controversial figures in American gay life over the past 30 years. He first incensed gay men in 1978 with “Faggots,” his eerily prescient novel that critiqued the gay community’s culture of promiscuity. And as a co-founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and the founder of ACT UP, the influential AIDS activist group, he became one of the most strident and passionate voices in the early years of the AIDS crisis. While making countless enemies, most notably New York Mayor Ed Koch, he was one of the people most responsible for drawing attention to the disease.

Over the last decade and a half, as AIDS has transitioned from a death sentence to largely treatable and gay culture has transitioned from the margins to somewhere closer to the mainstream, Kramer has remained (almost) as angry as ever. In 2005, he published “The Tragedy of Today’s Gays,” a transcript of a speech in which he attacked the younger generation of gay men for their apathy over gay causes and accused them of condemning their “predecessors to nonexistence.”

Next week, Kramer’s politics will get another turn in the spotlight when his 1985 play, “The Normal Heart,” opens on Broadway for the very first time. The largely autobiographical story centers on a group of gay men in the early days of the AIDS epidemic and stars Joe Mantello as Ned Weeks, a Kramer-esque activist desperately trying to draw attention to the plague, alongside a cast that includes Ellen Barkin, Lee Pace and “The Big Bang Theory’s” Jim Parsons. The play remains a highly effective, moving work that brutally conveys the desperation and terror that accompanied the emergence of AIDS. But nowadays, it also doubles as a history lesson for people who grew up long after the first wave — a role that Kramer sees as vital.

Salon spoke to Larry Kramer in his New York apartment about the importance of “The Normal Heart,” iPhone’s Grindr app and the problem with young gay men.

I saw a preview of the play last night with a friend. I think many of the ideas in the play will seem exotic and a little dated to a lot of young gay men.

Like what?

Like the idea of promiscuity as a political statement and that it would be treasonous or controversial for gay men to tell other gay men not to have sex, or to have sex with a condom. What do you think young people should take away from the play?

It’s our history. We’re gay. This was part of our history. This was the most horrible thing the gay population ever lived through. And yet it also represented — later on, with ACT UP, and the getting of AIDS drugs — the most spectacular achievement the gay population ever had. We gays did that.

I don’t know why so many gay men don’t want to know their history. I don’t know why they turned their back on the older generation as if they don’t want to have anything to do with them. I would like us to get beyond that.

But do you really think that lack of interest in history is particular to this generation?

You tell me.

Well, I’m 27, and I know that my formative images of gay life had nothing to do with AIDS. Ellen came out of the closet when I was in junior high and “Will & Grace” made gayness seem like a consumer identity more than anything else. Gayness wasn’t really linked with sickness is my mind, and so those early AIDS battles, I think, seem very alien to a lot of young people’s experiences.

I don’t know. I could understand what you’re saying. Sometimes when I go to schools, kids say that they’re taught to be non-confrontational or non-participatory now, almost like it’s not cool to have opinions and express them, which is sad. I hope we’re coming out of all that.

You seem to have some anger at the young gay population.

No more than the old gay population. I’m an across-the-board person. We have responsibilities toward each other, as family, as brothers and sisters. We’re all in this together. ACT UP was the most moving experience I ever had in my life. We were sick and dying and that gave everything a special glow of importance, but it showed us what we were capable of if we did do it.

You’ve had a famously acrimonious relationship with former New York Mayor Ed Koch, whose inaction about AIDS you blame for the death of many of its victims. Does he still live in this building?

Fortunately, in the other elevator bank so we don’t have to see each other. We pass occasionally, both of us making a big point of ignoring one another. As you may know, I once ran into him where we get our mail. He bent to pet my dog and I yanked her away and said something like: “No, Molly, that’s the man who murdered all of Daddy’s friends.” When I first saw him in the lobby, I screamed at him: “We don’t want you here!” as loud as I could across the length of the lobby and I was told by my landlord that we would be evicted if I did it again. So I didn’t. I like my apartment too much.

Coming out of the play last night, my friend and I both felt a perverse nostalgia for those early AIDS years we never lived through. They were obviously utterly terrifying and filled with sadness, but there’s also something appealing about having this galvanizing issue to unite gay men. We don’t have that as much now.

There are these issues now. It’s just that you don’t think of them as galvanizing, mainly because they’re not so life and death. I cite marriage, although I’m sort of fed up with how long it’s taken and I think we’ve gone about it the wrong way. I’m 76, and my partner is 64. I’ll obviously die before he does, and the way the laws are written it’s very hard to leave him anything of substance compared to what I have to leave. It all goes to taxes because we’re not legally federally married and that’s not fair, that’s just not fair. You don’t care about it at your age, but I care about it at mine, and there are a lot of older gays who should care about it as well. That should be a galvanizing issue. Anything that keeps us from being unequal should be galvanizing. I want what they have. I do. And everybody should. But again, people don’t think that way.

What has frustrated you about the move toward gay marriage in the country?

Just that it’s taken forever. I don’t think we should have taken the state by state approach because it just makes it go on, and then you have to re-sue and defend. Things need to go to the Supreme Court as fast as possible. There were ways it could have gone to the Supreme Court a lot earlier. If we lose at the Supreme Court, which everyone was afraid of, you just come back again. These [state] marriage we have don’t amount to anything. They’re feel-good marriages. They make relationships stronger and all that, but they don’t amount to a hill of beans in terms of anything legal or financial. You still need to pay federal taxes and you don’t get any of these benefits the government pays you if you’re heterosexually married.

The play suggests that one of the reasons there was so much meaningless sex in the gay community in the 1980s was because there was no gay marriage. Now that state marriages exist, do you think there’s been a cultural shift away from that meaningless sexual culture?

I think there’s still an awful lot of meaningless sex going on and the infection figures are still much too high and going up, so obviously there’s still too much careless sex going on. I don’t want to come out of this sounding like this prude. I never said don’t have sex, but what’s so hard about using rubbers? It doesn’t seem to require much intelligence to figure that one out. I don’t have much sympathy for people who seroconvert now, who know about AIDS. I don’t care if you were on drugs or whether you were out of it in the heat of passion or whatever. Your cock is a lethal instrument. It can murder people.

Are you familiar with Grindr, the iPhone gay sex app?

What?

It’s an iPhone application that shows you how far away other gay men are, so you can have sex with them.

No. I’d be happy to use it now if I thought it would do anything. I get horny just like anybody else, and David [Webster, Kramer’s partner] and I have been together a long time, so our relationship is now something else. I joined Daddyhunt or Manhunt and all those things, and posted my pictures, and filled out my questionnaire. And I got absolutely no response from anyone and it led me to wonder: What do older men do? It’s very sad that suddenly there’s no way to partake in all of this.

The interesting thing about Grindr is that it creates this map of your surroundings that’s really catered to gay men. You can log into it in your apartment and suddenly there are 100 people around you looking to hook up.

It sounds wonderful. I’m not against sex, I’m against being irresponsible. We have bodies and we should enjoy them, but we shouldn’t treat each other as things. That’s what it came to be in the [1970s] height of Fire Island [the gay party mecca], and I guess you could say the same about this Grindr thing.

It seems like the intense over-the-top party culture that Fire Island embodies — the kitschy nightclubs and circuit parties — are in the process of disappearing. I honestly don’t think they appeal to young gay people in the way they used to.

They were very drug-induced escapes. You really had to power your body for an enormous number of hours with an enormous amount of help. Someone said something interesting recently to me about why people did so many drugs in the 1970s: “It’s because it made it less painful, less difficult, less arduous, the life we led outside of the gay world.” Fire Island itself was and still is enormously competitive. You’re bartering with your body. Maybe people are more content with the sex online. I don’t know. I don’t see the gay world anymore. I don’t see it visually on the streets like we used to see it. I don’t know where it is. Do you?

Well, I think it’s less visible, and a lot of that has to do with the Internet. Gay ghettos are emptying out. There are fewer gay bars than there were before. And I think young gay people are more comfortable inhabiting the straight world and straight environments. I also think people have more straight friends.

Well, I’m glad I’m not your age anymore. Being gay was so much fun. And there were so many of us to have fun with — just being part of a very, very visible world where you saw people all the time and you socialized. I don’t see it now. I know they’re here. I know they’re in this building, but I don’t even know them as gay, even though I know they’re gay.

I am a gay person before I’m anything else. I’m a gay person before I’m a white person, before I’m a Jew, before I’m a writer, before I’m American, anything. That is my most identifying characteristic and I don’t find many people who would say that. The polls say the same thing: People do not identify themselves as gay. And that’s too bad. In fact, it’s tragic. It will prevent us from ever having what we deserve, I believe.