It's a sunny Monday afternoon at Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park south of Carmel on the California coast, and the kids from Western Wellspring Adventure Camp head down to the river for a swim. Back from a two-day, overnight backpacking trip in the Ventana Wilderness that included 11 miles of hiking and a close encounter with a rattlesnake, the campers are ready to get wet.

At least, the boys are.

The girls have just taken 25-cent, three-minute camp showers -- "I only shaved one leg!" -- and they're not about to get their still-drying locks soaked in dirty river water. Or maybe they just don't want to be seen in public wearing bathing suits. So they park on the bank, chatting, writing letters home or scribbling in their journals, while the boys horse around in the shallow water, splashing and laughing.

Millions of kids spend their summer at overnight camp, playing sports, building campfires and making friends. But the campers at Wellspring have a more urgent goal: to lose weight. Like other weight loss camps, Wellspring deploys a strict food and exercise regimen. But Wellspring's management bristles if you call their program a "fat camp," which they find derogatory, too negative. "We like the athletic metaphor," says Ryan Craig, a Yale-educated lawyer who is the president of Healthy Living Academies, which operates Wellspring. "We're transforming our bodies in the same way as athletes overcome biological barriers to transform their bodies." But unlike athletes, the kids aren't training for a big game or a race. They're in training for the real world after camp. Wellspring's motto is "Change for life."

The camp's method is to teach kids to deliberately fixate on food and exercise, to create a "healthy obsession," in the words of the camp's clinical director, Daniel Kirschenbaum, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago, who has also written a weight loss book by the same name. Campers keep journals in which they write down the calorie and fat content of everything they put in their mouths, and wear pedometers so they can count and record every step they take. Campers get rewards for being diligent reporters, garnering not only praise from counselors but treats, like a field trip to Starbucks or time on the Internet.

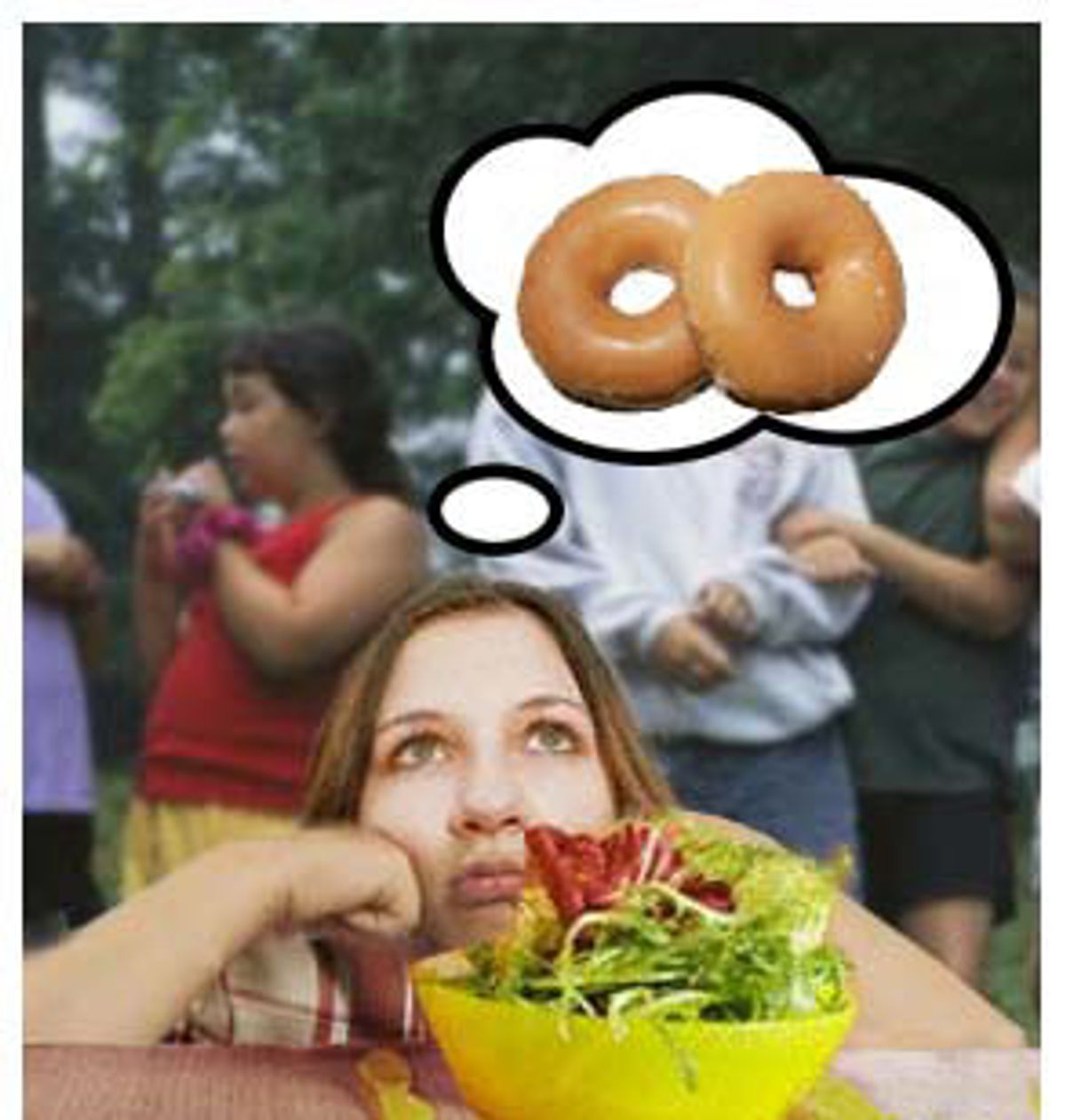

As I sit with them on the riverbank, it's clear the Wellspring girls are obsessed with food, all right -- the food they're not allowed to eat. Their talk is peppered with paeans to waffles, Pringles, beef and chicken. One girl, who has been at the camp only a week, pledges defiantly to drink a gallon of juice when she gets home. But the food chatter comes to a halt when the campers spy a girl nearby whose body is everything theirs are not.

The object of their attention is a prepubescent girl, no more than 10 years old, wearing a red-and-white polka-dot bikini. The girl's stomach is flat, her waist narrow, and she carries not an ounce of excess bulge. She ambles on some rocks, oblivious to the Wellspring campers nearby examining her with undisguised envy.

"I want to be tiny like that," whispers one Wellspring girl. "I want to kill her," sighs another.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

In August, I spent two days with a dozen Wellspring campers trying to understand what it feels like to be an obese teenager, to have one's body deemed nothing less than a public health crisis. I met 13-year-olds who authoritatively discussed their body-mass indexes as they might the latest Kanye West CD. Teens who know about the threat of Type II diabetes, once called "adult-onset diabetes," to overweight kids because some of them already have it; kids who can recite calories and fat grams from meals they'd eaten days ago. Two 14-year-old girls challenged me to try to name a diet that they hadn't already been on -- and failed at -- back home. Certainly, the kids I encountered were informed about health and nutrition. But is that knowledge -- and only four to eight weeks at Wellspring -- enough to help them end the cycle of weight loss failure? Is teaching them to be obsessive about food and exercise really the best way to help them shed pounds? And will weeks of deprivation at camp just lead to bingeing on Pringles and waffles when they are finally unleashed from their summertime stint in food prison?

To be accepted at Wellspring, a child must be at least 20 pounds overweight according to his or her body-mass index. But you don't have to put them on a scale to know that many of the kids here are much heavier than that, sometimes by 50, 60, 75 pounds or more. (In 2004, the average Wellspring camper was 75 pounds overweight.) What's striking about these teens, however, is that they don't really look that different from their middle- and upper-middle-class peers in suburban malls and fast-food joints. They represent the leading edge of the new normal. Yet these kids are spending a big chunk of their summer vacation to try to change that, with their parents shelling out $4,350 for four weeks of camp or $7,450 for eight weeks.

According to Wellspring's Web site, campers last year lost an average of 3.9 pounds per week. But there are no rigorous independent studies of American weight loss camps; the data about them is generated by the institutions themselves for marketing purposes. So, not surprisingly, all of the camps, including Wellspring, claim that their campers lose a lot. But no one knows if there are any long-term results from so-called fat camps. Some critics claim that all the camps give kids -- and their parents -- is ample servings of false hope.

"The parents ship the kids off, and when the kids come home, they've lost weight," says Abby Ellin, a former fat-camper and counselor, and author of the new book "Teenage Waistland: A Former Fat Kid Weighs In on Living Large, Losing Weight, and How Parents Can (and Can't) Help." "The parents think that's the end of the problem, and it's not. It's the beginning." A skeptic about weight loss camps, including the ones she attended, Ellin is cautiously optimistic about Wellspring: "Wellspring is actually trying to teach the kids. They're giving them therapy. They're giving them pedometers and making them write in journals. They're making them hyper-hyper-vigilant, which is good and bad. Their whole thing is a 'healthy obsession' with food, which is how you have to live in the world if you want to be a thin person."

In some respects, Wellspring feels like a military boot camp, training kids for a lifetime battle with their bodies. The brass is an advisory board of pediatric obesity experts and nutritionists with lofty pedigrees. But in the field, the charge is led by an Outward Bound veteran, Ryan Madamba, 33, along with a phalanx of uniformly trim, super-outdoorsy counselors, mostly in their early 20s, who take the kids backpacking, surfing, white-water rafting, hiking and biking.

When kids first arrive, they're stripped of contraband like cellphones, pagers, food and makeup, which is deemed an unnecessary distraction that just adds weight to backpacks on camping trips. Phone and Internet time isn't a right; it's a privilege that you have to earn by excelling in the program. Daily wake-up is at 6:15 a.m. Meals and snacks are served at set times to ensure that even though the campers are allotted just 1,200 calories and seven to 12 grams of fat a day, they won't crash and go into starvation mode.

And every meal is a lesson.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

After their swimming and riverside lounging, the kids gather around a picnic table and cut up the fixings for the night's dinner.

Lily, 13 from Santa Fe, N.M., has a diamond stud in her nose and a mane of long, dark brown hair framing her pale skin. She expertly chops garlic while musing aloud: "Baked garlic is so good." Then: "Oh-mi-gawd: Baked garlic with mashed potatoes and a hamburger!" Needless to say, none of that is on the menu that night.

The garlic will go into a spaghetti sauce with onions, basil, oregano and canned diced tomatoes. Before it's served, the evening's designated nutritionist -- another camper -- will write the meal's fat and calorie content on a mini-whiteboard so that the kids can copy down the information into their journals. Dinner has just 234 calories and 1.5 grams of fat, but if you opt for a sprinkling of Parmesan, that knocks it up to 254 with two grams of fat. Counselors use measuring cups and teaspoons to dole out servings into each kid's bowl, with the goal of teaching proper portion size. But the kids cook most things themselves.

All food and drink -- even condiments -- at Wellspring is divided into two broad categories: "controlled" and "uncontrolled." Campers can eat as much as they want of the uncontrolled foods as long as they "self-monitor" -- writing down the foods in their journal, including the calories and fat content, which they dutifully look up in their personal, pocket-size calorie-counter books. Uncontrolled foods include fruits and vegetables, like this night's side salad of green bell peppers, cucumbers and tomatoes, with no dressing. This is the definitely the only place I've heard a teenager say with no irony: "Oranges rock." Broccoli and green beans are also all-you-can-eat this evening. Coffee and tea, as well as condiments like ketchup, Tabasco, mustard and the sugar substitute Splenda, which has no calories and no fat, can be used with abandon, too.

The camp could ration all foods, and just serve them to the kids and be done with it. But choosing to stop eating when they've had enough is one of the biggest challenges the campers will face back in the real world. So Wellspring introduces an element of choice, allowing the kids to eat as many, say, oranges as they want, perhaps even bingeing on them. Having to record what they eat in their journals is supposed to make the campers at least conscious that they're doing it.

Campers are instructed to consume fewer than 20 grams of fat a day (about the amount in one kid's serving of fries at Denny's), a goal they're supposed to try to maintain when they get home. No one expects them to record every morsel of food that goes in their mouths forever -- that's unrealistic. But in the best-case scenario, a muted version of a fat and calorie tape will always be running in the back of their minds.

I am not surprised to discover that the campers binge on uncontrolled foods, especially those with little or no calories. Two 14-year-old girls, Samantha ("Samme") from Albuquerque, N.M., and Alexandra ("Alex") from Quincy, Calif., brag that they each average 35 cups of tea a day. It's a boast that draws an incredulous "How is that even possible?" from director Madamba. "We have a lot of these," says Samme, brandishing a large, green plastic tumbler. "And they count as two." Then she mutters to the other campers: "I think that they're going to start controlling coffee and tea."

The kids also go to town with the spices, dumping Mrs. Dash, garlic powder and Tabasco sauce on their spaghetti, trying to bring some flavor to the rather bland fare. And they pour packet after packet of Splenda -- no calories and no fat! -- on their chunks of unsweetened canned fruit. The campers do sometimes get treats -- low-fat and low-sugar versions of pudding, angel food cake, s'mores or brownies. This is supposed to make them feel less restricted, according Chris D'Andrea, 27, the campers' "behavioral coach," who holds a master's degree in sport and exercise psychology, and leads the kids in group and individual therapy several times a week. More like normal dessert-eating teens.

The teens at Wellspring are normal in many ways. Back home in Palm Springs, Calif., Joann, 16, who goes by "Joey," is on the swim team. Towering over the other campers, swinging her long brown hair, she totes around a binder that has photographs of her friends and family decorating every inch of its cover. "I was at camp on my sweet 16," she tells me, savoring the exquisite irony. Get it: Sweet 16 at a weight loss camp? Joey frequently moans about missing her boyfriend and hopes for mail from him. She was also at Wellspring during the couple's most recent monthly "anniversary."

Being a fat kid, it seems, isn't what it used to be. The teens at Wellspring may be overweight, but they're not hiding from life, or opting out of romance or activities. One camper is a cheerleader back home; another likes to play volleyball and works two after-school jobs. Missing friends back home was a frequent lament. I did meet shy kids, who seemed as if they'd be a lot more comfortable alone in front of a computer screen than with their peers. But I also met major social alphas and super-extroverted comedians, who sang and rapped and joked. It may be time for the stereotype of the overweight social outcast to get a big fat makeover.

Over spaghetti, Joey notes happily that she and the other campers got to have angel food cake to celebrate her sweet 16, and that her birthday also coincided with a field trip to Applebee's, where the kids learned the fine art of finding a healthy meal amid such artery-busting temptations as queso dip and chips and all-you-can-eat riblets. At Applebee's, the campers were allowed to order whatever they wanted -- as long as they recorded the fat and calories in their journals. Most of them stuck to the restaurant's Weight Watchers menu. But one camper, who didn't want to be named because she felt so guilty, confessed that she ordered the fish and chips, which contained 83 grams of fat -- as much as a Wellspring camper eats in a typical week. It's a shame known only to her journal and the counselors.

After dinner, Joey hands out Viactiv, a chewy, chocolate vitamin supplement, which she explains is "our source of calcium," adding: "We get skim milk when we go to the Academy. That's big for us. Small pleasures become awesome." The Academy is the Academy of the Sierras, a year-round, weight loss boarding school in Reedley, Calif., that is based on the same principles as Wellspring and owned by the same parent company, Healthy Living Academies, a division of Aspen Education Group. The company opened the Academy of the Sierras last year, and charges $5,500 a month for tuition and room and board. The Wellspring campers will visit the school in a few days to stock up on more supplies, and maybe have a visit from their parents, before heading back to the woods.

After dinner, there's much gossip about the upcoming camp dance. One of the older boys, a sandy-brown-haired giant, pays one of the smaller girls the ultimate compliment: "You have no reason to be here."

"Yes, I do," she insists, sticking out her belly to prove it.

That evening's big event is a ceremony in which the kids find out if they will ascend to the next rung in the camp's elaborate hierarchy. Using surfer lingo, kids start out as "beachcomber" and move up through "grom" and "maverick," eventually hoping to earn the title of "big kahuna." This behavior-modification program uses positive reinforcement to try to encourage kids to stick with the program. They advance through the levels by increasing their average daily step count from 10,000 steps to 25,000, consistently writing down all food, calories and fat grams, recording what they've learned in their journals and being good role models to other campers. At the ceremony, campers will get beads representing their new status, which they wear at all times on necklaces. As they climb through the ranks they also earn privileges like a movie outing or extra phone time.

To get to the levels ceremony, the kids have to walk over a narrow wooden-plank bridge, which is only two boards across. It traverses the rushing Big Sur River, and as the kids line up, one boy hoots at another: "You'll break it!" But his taunt is immediately met by a chorus of "That's MEAN!" from his fellow campers.

Clearly, fat jokes aren't funny here.

The counselors cajole the campers to organize themselves by their ranks in a circle. Surrounded by sycamores with an acorn woodpecker yakking in the background, Jessie Dean, 24, the program director, tells the campers that there is one thing that holds them all together, no matter what their level or rank: "All of you are here because you want to lose weight," says their lean director. "You want to have a healthy lifestyle."

As the new levels are announced, and beads handed out, the campers clap and hug the honorees. Samme, the cheerleader from New Mexico, who holds the camp record for most steps walked in one day -- 54,016 -- has reached "big kahuna." Her eyes well up with tears.

Now all the kids, even the ones who didn't move up, are rewarded with an evening treat: no-sugar-added, 50-calorie, nonfat hot chocolate. The kids break into small groups, chatting over their mugs as it starts to get dark. Not everyone is inspired by the big ceremony. Lily, who has been here eight days now, grumbles to her friend Nancy, 13, of Bakersfield, Calif.: "I don't want to be here," she confesses. "My parents forced me to come. I'm not even that overweight. I barely qualify."

Nancy bursts in with: "I don't look that fat, do I?" She pulls up her sweat shirt, sticking out her belly.

"You look, like, 150," says Lily, supportively.

Nancy, who is closer to 200, says: "That would be so awesome."

Lily insists that she could have lost the weight without having to suffer the indignities of camping. "I was only 21 pounds overweight," she says. "I could have done it at home."

Not that she wants to. On a hike the next day, Lily makes a startling announcement: "I don't want to lose weight," she declares. It's her parents who want her to.

"My mom is embarrassed about the way I look," says Lily, who weighed 170 pounds when she came to camp and at five feet, five inches is supposed to weigh between 119 and 149 pounds according to the BMI. "She's afraid I'll keep gaining weight. She doesn't want an obese kid, because no one will be my friend and no one will talk to me, and I'll be really unhappy."

Lily says that the nutritional information taught at the camp isn't new to her because her parents, whom she describes as "health and nature freaks," hammer it into her all the time. "They just got sick of telling me and wanted someone else to tell me," she says. At home, she swears she's allowed to eat something that's not 100 percent organic only on her birthday.

Lily's confession is met with shock, as if she had declared "God is dead" at a revival meeting.

It's one thing to complain about the camp's bland food or all the exercise or how gross it is going to the bathroom in the woods. But who doesn't want to be thinner?

"You don't want to lose weight?" another girl asks incredulously.

"No," Lily says firmly.

"You're the weirdest person I've ever met in my life!" the other girl replies. "Even tiny girls want to lose weight." The campers chime in about how incredibly annoying those tiny girls are, the ones who whine about how fat they are but who are really a size 4 or 6 or 8. But a big girl who doesn't wish she were slimmer? The campers can't even comprehend it.

Maybe Lily really is the only 13-year-old girl in America without a bad body image. Or maybe she's just rebelling against her parents, who have shipped her off to camp when she'd rather be back home hanging out with her friends. But it also bears pointing out that she's not that heavy -- just 21 pounds overweight at the beginning of camp -- making her one of the slimmest teens at Wellspring. Maybe her parents are right and she would have continued gaining weight if she were at home. But maybe not.

At breakfast the following day -- cream of wheat or cornflakes with powdered milk -- the kids, who are only weighed every couple of weeks, speculate about who is losing how much. Samme, the new big kahuna, says that she lost 14 pounds in her first month at camp, and was 164 pounds at her last weigh-in. She's staying only six weeks because she has to get back to school. She wished she'd dropped more, but, ever positive, she says: "That's 14 less I gotta lose." Her personal goal is to lose 30 pounds at camp. Her dream is to someday weigh 130 pounds.

After morning stretch circle, campers move on to their next site, an hour up the road in Monterey. Morning snack is a brown-rice cake with a low-fat peanut butter substitute, which tastes vaguely like the real thing, with 85 percent less fat. Lily declares the food at Wellspring unequivocally "gross." "None of it is real," she says. "Not real peanut butter, not real sugar, not real hash browns. It's the low-fat, dehydrated version. I need a burger really bad right now!"

Lily raises a good point: How healthy is it for growing kids to eat so many chemically laden food substitutes? Isn't it possible to eat a really low-fat diet, even fewer than 20 grams of fat per day, that doesn't feature Splenda as a major food group? Wellsprings' president, Craig, says that, ideally, they'd serve campers fresh, whole foods with most of their protein coming from vegetables, but that would be so far from the diet they eat at home, they would reject it. So instead, the camp serves them foods that bear a resemblance to what they're used to, just lower-fat versions.

Later in the day campers who have advanced to "maverick" will take a field trip to Starbucks, but not without some serious advance planning. Jackie Windfeldt, 23, the camp's nutrition instructor, hands out copies of "You, Starbucks and Nutrition," a brochure detailing the calories and fat in all the drinks served at the coffee chain. As the kids start scrutinizing their options, Windfeldt recommends the tall, light, mocha Frappuccino, which is 140 calories and 1.5 grams of fat. "Remember to ask for nonfat milk," she pleads.

Alex, Joey and Samme pile into one of the camp's white vans and start checking their looks in the rearview mirror. Grunged out in clothes that they've been camping in, with no makeup and not more than a three-minute shower in days, they're embarrassed to be seen in public. But as counselor Krissy Elsemore, 23, gets them on the road, the girls' spirits lift. They crank up Bobby Valentino's "Slow Down," singing along and dancing in their seats.

"Slow down never seen anything so lovely/Now turn around and bless me with your beauty, cutie/A butterfly tattoo/Right above your navel/Your belly button's pierced too just like I like it girl ..."

"When I get really skinny and toned, I'm going to get a butterfly tattoo on my bellybutton," says Joey, adding, apropos of nothing, "I hate skinny people." No one replies.

As Elsemore circles the parking lot, the campers get even more pumped up. "We're big fat people! Let us get our big fat coffees," shouts Joey, drawing high-fives from the other campers. As they walk down the street to the Starbucks, they pass restaurant after restaurant exuding temptation: "Sushi! All-you-can-eat buffet! Smell the sushi," says Alex. "Sushi's a healthy option, when you get home, guys," says Elsemore, trying to turn even the walk into a teaching moment.

Windfeldt, the nutrition guru, stops the group on the street before they go into the cafe: "Do you guys remember what you have to say?" "Nonfat!" comes the chorus of replies.

Alex, Samme and Joey settle on a venti, nonfat, sugar-free, vanilla, caramel macchiato with 240 calories and one gram of fat. It's relatively healthy compared with some of the milkshake-like options here. But it's also clear that the kids can't help seizing their chance for more of a good thing. They're entitled to just a "tall," the Starbuckian euphemism for a small. But they can upgrade their snack to a bigger size by spending shaka beads that they've earned at camp. Those are tokens that counselors hand out to say "Right on!" to a camper who has done extra chores or just shown a good attitude on a particular grueling hike. Alex, Joey and Samme all decide to take the supersize upgrade.

The kids relish their carefully selected coffee treats in civilization. Joey scribbles the calorie and fat information of her drink, on the back of her hand, so she won't forget to write it down in her journal back at camp. But I can't help noticing that their very fit counselor, the blond, outdoorsy Elsemore, who says her diet at home isn't that different from what the campers eat at camp, has ordered the most sensible thing of all: a 120-calorie, nonfat latte. She's not trying to lose weight; this is just how she eats. And it's healthier behavior than that of the teens who are devoting their summer break to slimming down but can't resist supersizing, given the chance.

It's impossible to predict whether the campers will be able to bring even a semblance of discipline into their normal lives when they leave Wellspring. To get parents on board, Wellspring invites them to try two days of the program at the end of the summer so they can see how their kids are used to eating and exercising. Campers are also required to self-monitor when they get home through a Web-based, three-month aftercare program. D'Andrea, the behavioral coach, will also check in with the campers online during those months, and they can chat with other campers on the site. But last summer, only 33 percent of Wellspring campers used the aftercare program. The site has been upgraded to try to make it easier and more appealing, but who knows if that will translate into more users.

Will Samme, Joey and Alex take home anything from Wellspring besides temporary weight loss? I think so. If not a belly toned enough for a tattoo, they'll have some new tools to help them as they struggle with their weight, probably for the rest of their lives. Maybe they'll dig that dusty pedometer out of a drawer when the pounds start to creep back, or unearth that calorie-count booklet and start a new food journal.

For now, Samme is planning the dream lunch she'll have when she gets home. And, no, Pringles, waffles and a gallon of juice are not on the menu. Instead, she says, she'll opt for refried beans, lettuce, low-fat sour cream and baked chips.

That's 305 calories and four grams of fat.

Shares