Those of you who are not movie stars, magazine editors, fashion publicists or morning show hosts may never have heard of Tom Ford. Those of you who have may be surprised to learn that he has anything to do with Hollywood, short of deciding which frocks its inhabitants should don to walk down a red carpet.

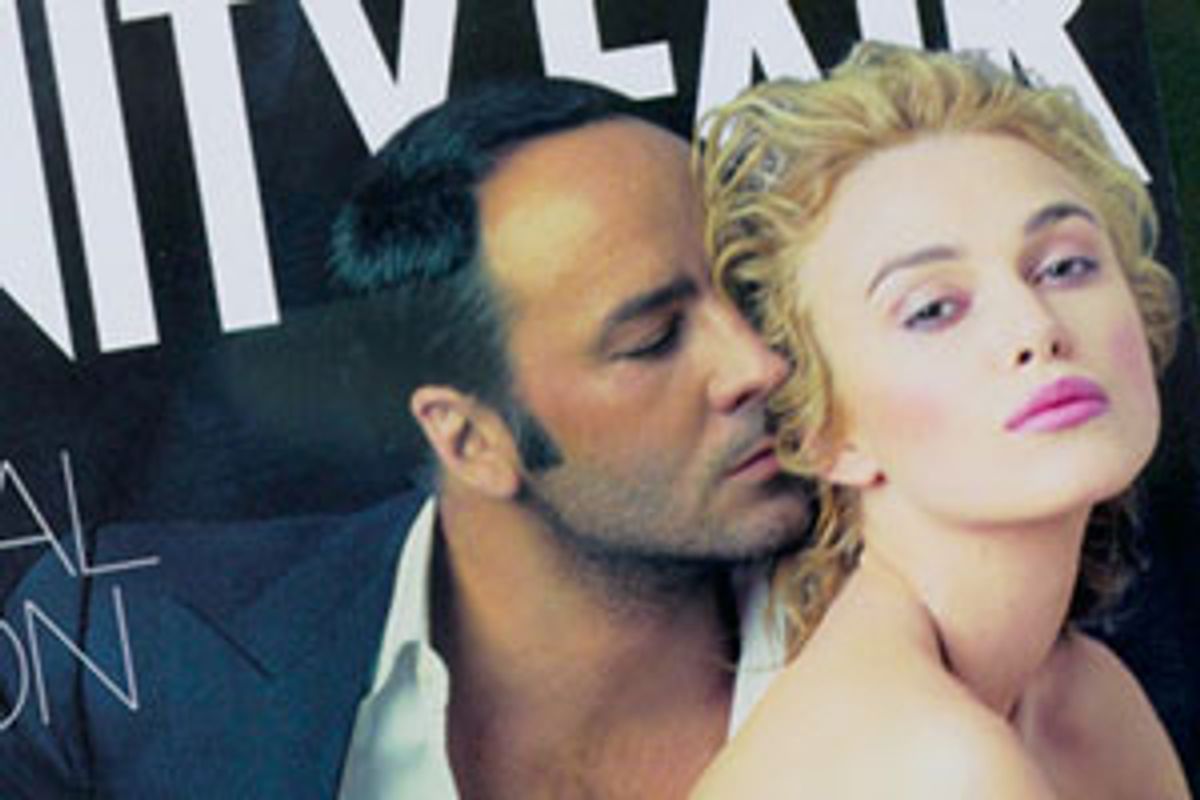

Yet Ford, who became known in certain circles for revivifying the moribund Gucci brand in the 1990s, has gotten himself so deeply confused with the movie stars he used to dress that this month finds him on the cover of Vanity Fair's annual Hollywood issue, on sale nationally today, sniffing the ear of naked "Pride & Prejudice" star Keira Knightley. And while much has already been made of Ford's manically narcissistic decision to appear clothed next to nude starlets Knightley and Scarlett Johansson on the magazine's cover, that over-the-top orgy of self-love, misogyny and outright idiocy on Page One is just a preview of what Ford, the issue's guest editor, has brought to its inner pages.

But let's get the cover out of the way: Rachel McAdams ("Wedding Crashers," "Red Eye," "The Family Stone"), one of the women scheduled to pose for this year's cover, arrived at the photo shoot only to learn that Ford wanted her naked. I had not thought a willingness to disrobe was a condition of appearing on the front of Vanity Fair, but reluctant ecdysiast McAdams not only lost her spot, she is mentioned in the magazine only as "a certain young actress" who "bowed out when the clothes started coming off," thus squelching "Ford's plan of having a gorgeous female threesome." There you have it, ladies, straight from Vanity Fair: We don't care if you star in three successful movies in one year; if you won't get naked for a "threesome," you can forget your spot in our pages!

As for Ford's claim, to editor Jim Windolf, that it was an "accident" that he plopped himself in the middle of the cover shot (fully dressed, because only the chicks have to take it off), a quick glance at the magazine's cover line ("Tom Ford's Hollywood"), its cover-photo caption ("Ford's Foundation"), its full-page contributor's bio of Ford, the letter from editor in chief Graydon Carter titled "Vanity Fair's Tom Ford Moment," a story about the making of the magazine called "Welcome to Tommywood!" and multiple pictures of Ford (walking sexed-up 12-year-old Dakota Fanning to her photo shoot, taking a bite out of Mamie Van Doren's inflated breast, strutting around in Wellingtons) provide subtle clues that there is nothing "accidental" about Ford's megalomania.

Aside from himself, what has Ford chosen to feature in his vision of Hollywood? By the numbers: Seventeen women (average age 31) and 19 men (average age 34). There are 16 visible female nipples (erect or exposed) to 17 recognizable female faces. Only five of the women are over 30, and two of them -- 75-year-old Van Doren and 38-year-old Pamela Anderson -- are honored not for their talents, exactly, but for their identities as "The Breast Friends." There are three female ass-cracks, one naked headless woman (in a photo of "Shopgirl" star Jason Schwartzman), two manicured female feet (for Viggo Mortensen to tickle), one pair of shapely female legs (upside down, for Topher Grace to maneuver as if he might at any moment spread them and dive) and one giant Dada-ist breast on a golf course in front of a featured plastic surgeon.

There's much to be said about the appeal of a well-placed arm, leg, breast. But extremities tend to be more compelling when attached to, say, a body. Ford is not celebrating the female form: He's hacking it apart and selling off the parts to male stars in need of girl-flesh to gussy up their own boring images. (For more on the use of disembodied lady parts as sales devices, see Women's Studies 101 chestnut "Killing Us Softly.")

For those women lucky enough to remain intact for the portfolio, total nudity seems to have been encouraged. (Ford had joked that this would be the "all-nude" edition of the magazine, but that edict seems only to apply to the babes.) Five of the women appear to have been photographed naked. They include Sienna Miller, topless but sterile, and Natalie Portman, gilded but folded in on herself. Angelina Jolie lies on her belly in a bathtub, while Jennifer Aniston curls into a protective ball of skin and boots. Both Jolie's and Aniston's photos appear to have been castoffs from V.F. shoots they did earlier this year. Apparently, it was more important to include these old -- but nude! -- shots than it was to photograph less-exposed, and more persuasively "New!" stars like Amy Adams, Michelle Williams or Rachel Weisz, none of whom are in the issue.

But it's Joy Bryant's picture that is most disturbing. The African-American Bryant, her blurb tells us, earned straight A's in Bronx public schools, went to Yale, scored roles in "Antwone Fisher" and "Get Rich or Die Tryin'"... and now appears in Vanity Fair, where she is called "The Wild Honey," and photographed wearing expensive jewelry and nothing else. Congratulations, Joy Bryant, on breaking class and racial barriers so that you can be reduced to your breasts and bling on the pages of a national magazine!

I don't mean to be a scold; I have nothing against nudity in magazines. One of my favorite images from Hollywood issues past is of Sigourney Weaver, dressed in a fishnet body stocking and boots, lying on her back, one breast very visible. The photo was aptly dubbed "The Force." In it, Weaver looked fierce, turned on by her own long body. That picture might fairly have been described as a "Do Me" shot, but it projected an unspoken warning: "Do me wrong, and I'll kick you hard with my big boots." Sienna Miller looks like if you did her wrong she might pop another Klonopin and doze off.

Ford shows us a girl on a car -- the relatively unknown Michelle Monaghan, splayed upside down so that she's further unrecognizable -- and 10 pages later, a girl in a car. (Zooey Deschanel, dubbed "The Living Doll" and dressed in lacy tights with legs in the air for a particularly twisted piece of cheesecake; it looks as if she's been kidnapped and stuffed in the back of the car, awaiting assault.) In contrast to the maturely decked-out child-star Fanning, Ford pictures Reese Witherspoon, Oscar nominee and mother of two, in a baby-doll dress, clutching a dolly. Witherspoon's photo caption reads "The American Beauty," but it looks like she should be called "Betsy-Wetsy." The only great image of a woman is of Michelle Yeoh, pulling herself up on a trapeze in an evening gown.

With that notable exception, Ford presents femininity as passive, plastic. These are mannequins, their energy extinguished, or at least temporarily bronzed, like Portman. They recall the creepy female figures whom Ford groped and squeezed in a ludicrous photo spread in W this summer, which he passed off as commentary on plastic culture, but in which only the women were dummies. In V.F., he bites Van Doren's false breast, sniffs Knightley's neck; all this chomping and snuffling may seem less predatory because Ford is openly gay, but that only makes clear that his attention isn't about passion, but about consumption and commodification. The women's bodies in Vanity Fair are -- as they were in W -- props, toys, jokes.

To be fair, the V.F. men don't win out, either, though they did get to keep more of their clothes. A couple (Joaquin Phoenix, looking like a Tiger Beat centerfold, and Eric Bana) are semi-shirtless; Jonathan Rhys-Meyers might be naked, but since he's only photographed from the neck up, it's tough to tell. Only poor Taye Diggs comes close to true bare-assed nudity -- a black man on a bear rug, an image reliant on some of the most repugnant stereotypes of black male sexuality. Mostly, though, the guys are in suits and tuxes.

Then there's George Clooney in an unbuttoned shirt and Wellies directing a bunch of half-submerged anonymous women in flesh-colored bras and panties in a sendup of Géricault's "The Raft of the Medusa." Clooney is dubbed "The Boss" in honor of his growing role as gentleman auteur, but this image makes no sense. His movies, "Good Night, and Good Luck" and "Syriana," are not filled with anonymous broads. Ford told ABC that he conceived of the shot as "every woman's dream" (Oh, to stand in cold water and wet underwear while getting bossed around by George Clooney!), but that's a lame line. These women are there purely for, well, tits and giggles.

At the front of the magazine, editor Jim Windolf optimistically opines, "Taken as a whole, the pictures remind us that, beneath the trappings of wealth and carefully tended public images, the film industry remains a community of artists." But Tom Ford's Hollywood actually does the opposite of what his editors may have hoped.

Previous Hollywood issues have included reunited casts from beloved movies ("Carnal Knowledge," "The Big Chill," "Fast Times at Ridgemont High") and family portraits (the Hustons, the Goldwyns, Angelina Jolie with father Jon Voight). Often, the photos have spoken to each other; last year, Hilary Swank charged down a beach in a bathing suit, her body hardened for her role as a boxer in "Million Dollar Baby." On the next page was the reunited team behind "Raging Bull," a film for which Robert De Niro famously transformed his body to play boxer Jake LaMotta. Less artistically ambitious groupings have included a photo of survivors of Hollywood's Blacklist. It wasn't sexy, but it was a reminder that Hollywood is a place with a history, with politics, with families, with consequences.

Maybe Tom Ford doesn't want to look at a bunch of octogenarians. And that's fine. But then he should present a lucid vision in their place, and he does not. His "new" Hollywood includes 13 subjects who have been featured in previous Hollywood issues. He has claimed that his criteria for inclusion in the portfolio involved asking himself: "Am I tired of seeing them?" I don't know where Ford has been hanging out, but if I see one more picture of Angelina Jolie or Jennifer Aniston sipping a latte, browsing at Barneys, picking up dry-cleaning or pulling out of a parking lot, I'm going to kill myself. I don't care if they're naked.

But the terms of inclusion seem shaky in other ways as well. Vanity Fair editors write that Miramax pugilists Bob and Harvey Weinstein balked at Ford's idea of photographing them mud wrestling, and Ford tells Windolf that "Munich" star Eric Bana "wasn't comfortable" appearing in just a Speedo. Why is it OK that the Weinstein boys appear next to each other in suits, Bana got to wear a robe, but Rachel McAdams is not in the magazine? Why is it OK to run a photograph of a plastic surgeon in the Hollywood issue, but not a single director or screenwriter who's not also an actor? Maybe all this isn't even worth pointing out. As the L.A. Times' Robin Abcarian wrote about V.F.'s cover, in Hollywood "the combination of the dressed male and the naked heterosexual woman is merely a metaphor for how things are, have always been, and will probably always be."

Not that Hollywood isn't built -- it has always been built -- in part on skin. But what has made it America's most successful product has been the seesaw tension between the vapidity and the complexity, the aesthetic and artistic, performance and embodiment. As soon as we give ourselves over entirely to the fake, the plastic and the insincere, we destroy the balance, relinquish any hold on film as art, and descend into idiot adolescence.

I know, I know. I'm just rising to Ford's glistening bait. As Liz Smith wrote in her syndicated column on Sunday, Graydon Carter is smart to have put out an issue that everyone is so angry about that they can't stop buying it. According to Abcarian, V.F.'s Web site got 3.1 million page views on Tuesday and Wednesday, which spokeswoman Beth Kseniak called "a whole lot more than normal."

But before Graydon Carter -- a vocal critic of the Bush administration -- pulls a muscle patting himself on the back, maybe we should consider that dumbing down the discourse and appealing to the lowest common denominator are tricks that help not only to sell magazines, but to win elections. Shouldn't we aim higher?

Shares