As I type, I hear my daughter playing in the living room. I hear the infernal toy that says "Moo," "Woof" and "Quack." I hear Bess laugh and squeal. I wish she could be laughing and squealing with me. But Bess is with the other woman in my marriage. My daughter is with her nanny.

About five months ago, as my husband and I sat on our couch interviewing the woman we ultimately hired to be our daughter's caretaker, I felt like the Lily Tomlin character Edith Ann: a kid playing dress-up, spindly legs poking over the high-up edge of a grown-up chair. What do you like about being a nanny? How will you handle an emergency? I tried dutifully to follow the interview suggestions provided by my neighborhood parents organization. But who the hell did I think I was? I didn't know how to hire someone to take care of my kid -- I didn't know how to take care of my kid. And since when was I one of those nanny-having mommies? My grandparents were socialists, for chrissake.

Then something she said, something not that important in and of itself, gave me one of those rare, precious moments of maternal clarity. It was something about which playground she preferred and why, or how she'd take kids to look at the animals in the pet shop window. It was something about how she said it. At that moment, I actually got excited, excited for Bess to have a nanny, excited for Bess to have this nanny. At that moment, I didn't feel looming jealousy or guilt; I pictured the two of them off having adventures together, in a jaunty girl-and-governess fantasy from storybooks. And in that moment, I knew that putting my daughter in someone else's care while I worked, while not Plan A (Plan A being a disruption in the space-time continuum that would allow me to both work and hang with Bess full time, or a wageless society that still had HBO and sushi), was really, truly going to be OK.

And it is OK -- though it's certainly not always like that jaunty fantasy. (The real dream-come-true part is that my in-laws live around the corner and take wonderful care of Bess two days a week, which is how we can afford a nanny for two more days.) Even the most charmed arrangement is not without challenges and complications. Early on, I found myself blathering to Bess's nanny, who is from Barbados, about my ancestors' (not the socialist ones) complex relationship with black people (insofar as "master/slave" is "complex"), just, I guess, to demonstrate that I had thought about these issues. And there's this clichéd working-mom moment from the other day:

Me, all aflutter: Have you seen how well she stands up?!

Nanny: Yes, she's been doing that with me for weeks.

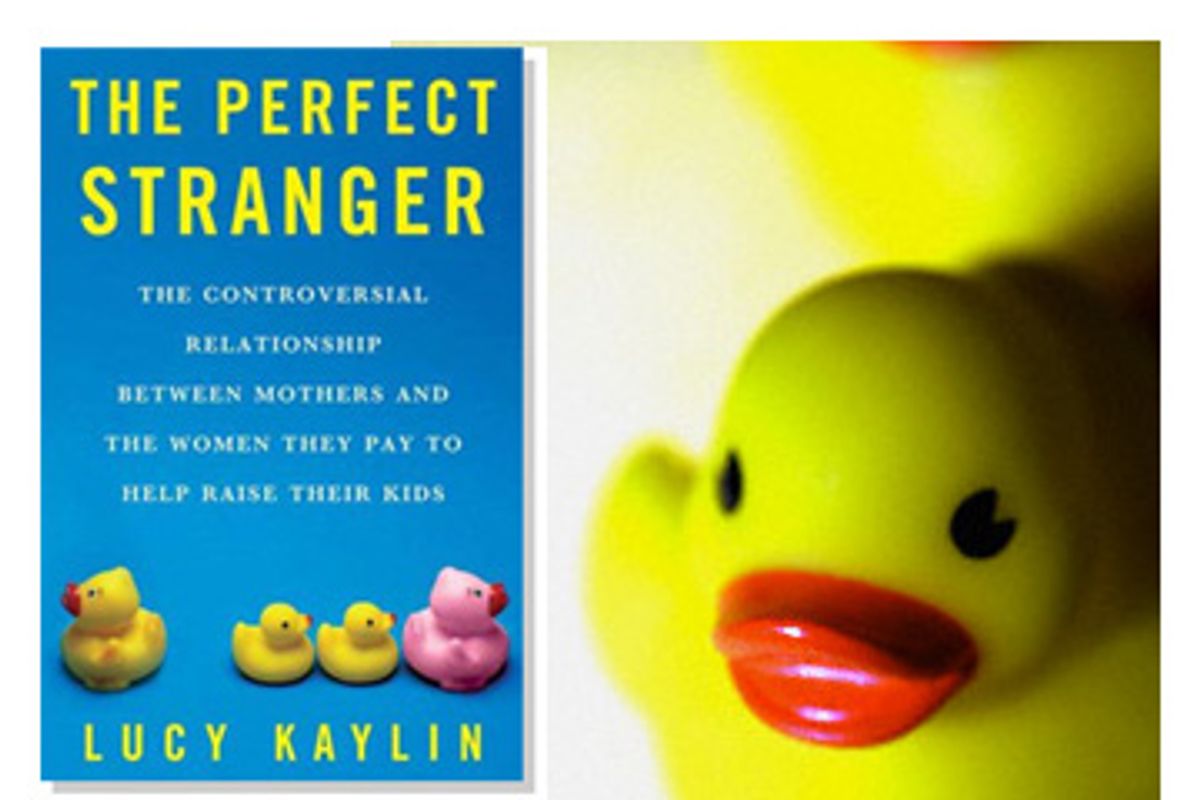

Separation anxiety, race and class, our very identities as women and parents: This is precisely the bumpy terrain that Lucy Kaylin explores in her new book, "The Perfect Stranger: The Truth About Mothers and Nannies." Said "truth" -- refreshingly -- is not, say, research twisted to assert that mothers who employ nannies have higher rates of self-hate, or that their children tend to grow up to be sociopaths. Kaylin's book -- her own nanny story, woven into interviews with other mothers and nannies, too -- shows that, actually, it's messier than that.

According to Kaylin, there may be as many as 1 million women now working as nannies in the United States. Their employers negotiate everything from pay scales to power dynamics in their own homes, all the while knowing that -- with so many choices available to them -- at some level, no matter what they do, the world outside will judge them. (Oh yes, and they will judge themselves.) "Hiring a stranger to help raise your kids -- funny how an act designed to simplify your life can wind up being the trickiest, most controversial thing you'll ever do," writes Kaylin, executive editor of Marie Claire and a mother of two children, whose nanny, Hy, has been with the family for 10 years.

Kaylin addresses that controversy without flinching. She cites, for example, the color-based pay scale, with an acquaintance's "Swedish" nanny at the top ("There is an element of status in being able to afford [a white nanny] ... it's something to be crowed about, like granite countertops"), and quotes Hy's spot-on remark about their separate spheres: "If it weren't for the kids, I wouldn't know you and you wouldn't know me." She criticizes "society's ambivalence" toward and lack of support for two-income families: "The message sent to moms is fend for yourself," she writes. But taken as a whole, her book is more well-crafted collage than polemic -- a portrait of the uneasy symbiosis between less-than-loaded two-income families and the "unprecedented influx of women from economically unstable places," of villageless mothers doing their best to raise a child.

In Kaylin's words, her book is also a "plea for absolution from the guilt, the fear, the gnawing ambivalence that comes with enlisting the help of a nanny." Absolution, she can't promise. But the book should at least serve as a big, huge greeting card to mothers who hire nannies -- one that says, essentially, though more poetically, "I get it." Kaylin spoke to Salon about the intricacies -- and, yes, the joys -- of the mother-nanny bond.

How did you decide to write this book?

It had become clear to me from talking to a lot of women that their relationship to their nannies -- and their choice to hire one in the first place -- is a huge, roiling issue. It didn't at all feel like my own private drama. It's the kind of thing that when anybody is given two seconds' permission to talk about it, they unload. So it seemed to me high time for a book that tried to wrap its arms around all of it.

Why is this so fraught now? We don't see Lady Capulet agonizing about Juliet's nurse.

It's especially fraught now because we have these "mommy wars" raging about whether we should go back to work, work part time or stay at home. They've been amplified by the media, but they do have some basis in reality. Get into it with moms and you'll discover in seconds how passionate and conflicted they tend to be -- and how aware they are that they may well be being judged.

And the whole nanny aspect of it becomes emblematic of the choice of a certain "camp." If your child is being pushed in a stroller by a woman from the Caribbean, it says everything about the choices your family has made. It makes it very plain to the world that this child is not being cared for during the day by her mother.

Where that really plays out is in the preschool and at the park -- places where there are children being tended to by a parent and children being tended to by a nanny. That can create all sorts of friction for you as a working mother who's going to drop in to these places when she can but not be as involved as others are going to be, and you can feel the stress and tension and judgment in that.

You mention a time when you happened to be at the playground, pushing your kid on the swing, and did not notice when he almost fell out.

It was really shocking for me. I love my kids more than anything and I've had all sorts of wonderful times with them, but the reality that day in the park was that I really didn't know that the saddle-style swing was too advanced for my 2-year-old, that he really needed to be in the bucket swing. And I really was watching the nannies more than I was watching him. I was craving that approval from them, being an actual mother in the park during the day doing my thing with my kids. And I blew it. I blew it big time.

How did your nanny, Hy, feel about the book and her strong presence in it?

A good thing about Hy and me is that we do talk a lot, and we'd talked a lot, even before I embarked on the book, about all of this stuff. She tells me stories about nannies, I tell her stories about mothers; we cluck a lot together, so we'd had occasion to raise some of these issues by way of gossip. So I don't think it surprised her that this was something I would want to be analytical about in the pages of a book.

Of course, I asked if it would be OK with her if I told our story, and I think she knew she could trust me when I told her that, really, ours was going to be the happy story. I was upfront with her that there was going to be stuff about race and class and unfairness and nannycams, but I think she felt comfortable with the way that I would portray it because she knows me awfully well.

What about the other nannies you included? How did you approach them?

I got a lot of referrals from mothers for nannies that I could talk to, and I also got a lot of help from an organization called Domestic Workers United, which is an advocacy group for domestic workers. I definitely felt that the nannies were more on their guard when they talked to me -- after all, I am a white, tape-recorder-wielding mother. I might not have been exactly who they wanted to unload with. But they were quite wonderful, very honest and astute. It really is part of their job to look the other way with so much of what goes on in a family, so I do think for some of them it was kind of fun to be able to speak their minds.

What were some of the things on their minds?

They're surprised by how infrequently some American parents eat with their children -- and pretty appalled by the way we feed our kids when we get around to it. (The chicken-nugget culture is surprising to a lot of them.) They're certainly shocked by American materialism, how it has become commonplace for 8- and 9-year-olds to have iPods and 10- and 11-year-olds to have cellphones and TVs in their rooms and whatnot.

And they are pretty shocked by how hard we work and the exhausting relay race we're running every day. They see the terrible compromises that American mothers make. They see us trying to assuage guilt with sacks full of trinkets from the airport; they're the ones we call at 5 p.m. to say we won't be home for dinner. One nanny told this heartbreaking story about a mother who had to refuse her child who was begging her to take him to the butterfly exhibit at the Natural History Museum. The nanny was just shaking her head, she was so saddened for this boy. And of course I'm shaking my head, too -- but I've been there, I've been that mother.

That probably made it hard to be an impartial interviewer.

Yes, little did nannies telling stories like that know that I was sitting there feeling guilty about exactly what they were describing. When somebody holds the mirror up to you like that, it's fascinating and difficult. I see what a cliché I've become, you know, when I come in the house with my hard shoes and dark clothes and I'm hugging my kid with one hand and working the BlackBerry with the other. You see yourself like that and it's awful; you're exactly the person you have long decried or felt superior to. A nanny can give you a really clear perspective on what it looks like to them.

Like the time Hy told you to kiss your husband.

Right. Hy is very frank, and if she thinks something's wrong she'll say it. And there was this one day when my husband and I were being so harried, doing that "two ships passing in the morning" thing, and she literally gave me a command: She said, "Kiss your husband." I was about to run out the door without doing so. And I thought it was great because she has a really macro sense of our operation. It's not just "I've got to make the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches this afternoon and make sure they have their bath by 6." She really cares about the health of the whole family. She cares about people getting kissed before they go out the door. She knows that it matters. And God bless her, it does matter.

The media often focuses on this guilt mothers feel about leaving their kids with someone else. What are some of the positive things that women -- and children -- get from having nannies?

Well, there are developmental experts who say it's really important for a child to be able to form a bond with an adult outside of the parental unit. I'm telling you, when I read that I was just clicking my heels in the air. It was just nice to know that there might be some quantifiable developmental plus in my kind of having forced this dynamic on my kids.

We also know that mothers bring a lot of baggage to their kids, especially if they're high-achieving, ambitious moms who expect a lot. We all bring a measure of concern and anxiety and desire to every interaction with our kids. Are they coming along OK? Are they doing OK socially? Are they learning their alphabet fast enough? Are they giving us loving-enough hugs when we leave in the morning? We all have our concerns that I'm sure we wear on our faces when we deal with our children. The nannies aren't counting on [the kids] getting a high-powered education that's going to make them successes in the corporate world. I don't think that's really on their list of hopes and dreams for the day. And I think it can be quite fabulous for [children] to be cared for for long periods by someone who doesn't bring that kind of baggage to the relationship.

What are some of the ugly truths you discovered about the nanny-parent relationship?

The ease with which some mothers would talk about their preference for one ethnicity of nanny over another made me pretty uncomfortable. They like Caribbean women or they don't; they like Filipinas or they don't. They think Latinas are "cheerful" or they don't. And there are mothers who maintain a sort of delusional notion that their nanny is with them for the fun of it. And sometimes that can lead to exploitive behavior, with the mother rolling in late without telling the nanny or offering up the overtime because "she's there anyway" and "they're having such a cute time together" -- and losing sight of the fact that this woman has rent to pay.

What's your feeling about the effort in New York to pass a minimum-wage law for domestic workers, including nannies?

I think it's a great idea. It's just shocking to learn how systemically unfair the situation is. All sorts of workplace abuse can be rampant in private homes, because who's checking?

How do fathers feel about nannies?

You'd think in this day and age that fathers would be as affected by the presence of a nanny as we are, that they would be as involved as we are in child rearing -- since we do have these great, well-adjusted feminist dads these days, wearing Snuglis and going to play dates -- but the reality is, the brunt of the childcare still falls to the mother. If something goes wrong with the kid, [people] are going to look to the choices the mother made to see what went wrong. And there's just no sense in which a father is hiring someone to be his proxy when he brings a nanny into the home. The nanny is a mother figure. So as a result, it's the mother who's overseeing the relationship and managing it.

Nannycams: pro or con?

I support any mother doing what she feels she needs to do to provide care for her kids. And if her anxiety is so great about hiring a nanny that she has to get another set of eyes on the situation, fine. But it does not appeal to me at all. I never considered getting one. My feeling was that if I felt I needed to spy on [my nanny] maybe I wasn't there yet psychologically, maybe I wasn't adjusted sufficiently to the idea of a nanny to actually have one.

I also could never have a moment's peace if I knew the filming was going on at home and that I was going to be perpetually on the lookout for offenses. I interviewed a [mother] who told me, horrified, that her nannycam revealed that the nanny would take a lunch break and not interact with her toddler while she ate her sandwich. I don't feel like she should have to, frankly. This is an exhausting job -- if anyone turned a momcam on me, I'd probably be carted away. The nanny's got to go to the bathroom, she's got to have lunch, she might have to talk to a friend on the phone at some point during the day -- we all do in our offices in midtown. Why should she not be able to do that, as long as the child is safe and OK? There's a fair amount of trust you have to have in the woman whom you've hired, and at a certain point you have to let her do her job.

How would you respond to critics who might say, "Boohoo, you can afford a nanny in the first place, why all the bellyaching?"

Well, because the word "nanny" has such a fusty, Mary Poppins vibe about it, it's easy to imagine that hiring one is an incredibly fancy choice made by people with tons of options. And that's just not the reality anymore. The vast majority of women I interviewed, they struggle. No one's going to miss a meal, but these are middle-class women who work crazy hours, for whom day care is not sufficient coverage, and women who don't live around the corner and up the street from their sister or mother as they might have in another era. We're really on our own out here, a lot of us, in the cities of America, working these demanding jobs in careers that we may or may not like, because we have to have two salaries.

And women should not have to apologize for the fact that they want to work in the first place. It's all about striking compromises and minimizing the times and the ways that you disappoint the various people in your life. I believe that life should be a rich business. I believe that my kids, anyway, get a kick out of the fact that I work and have kind of a neat job, and that I'm an energized, busy mom with places to go and stuff to do in which they frequently participate. I think that way of life, one that includes a wonderful nanny, can set a nice example for our kids.

Shares