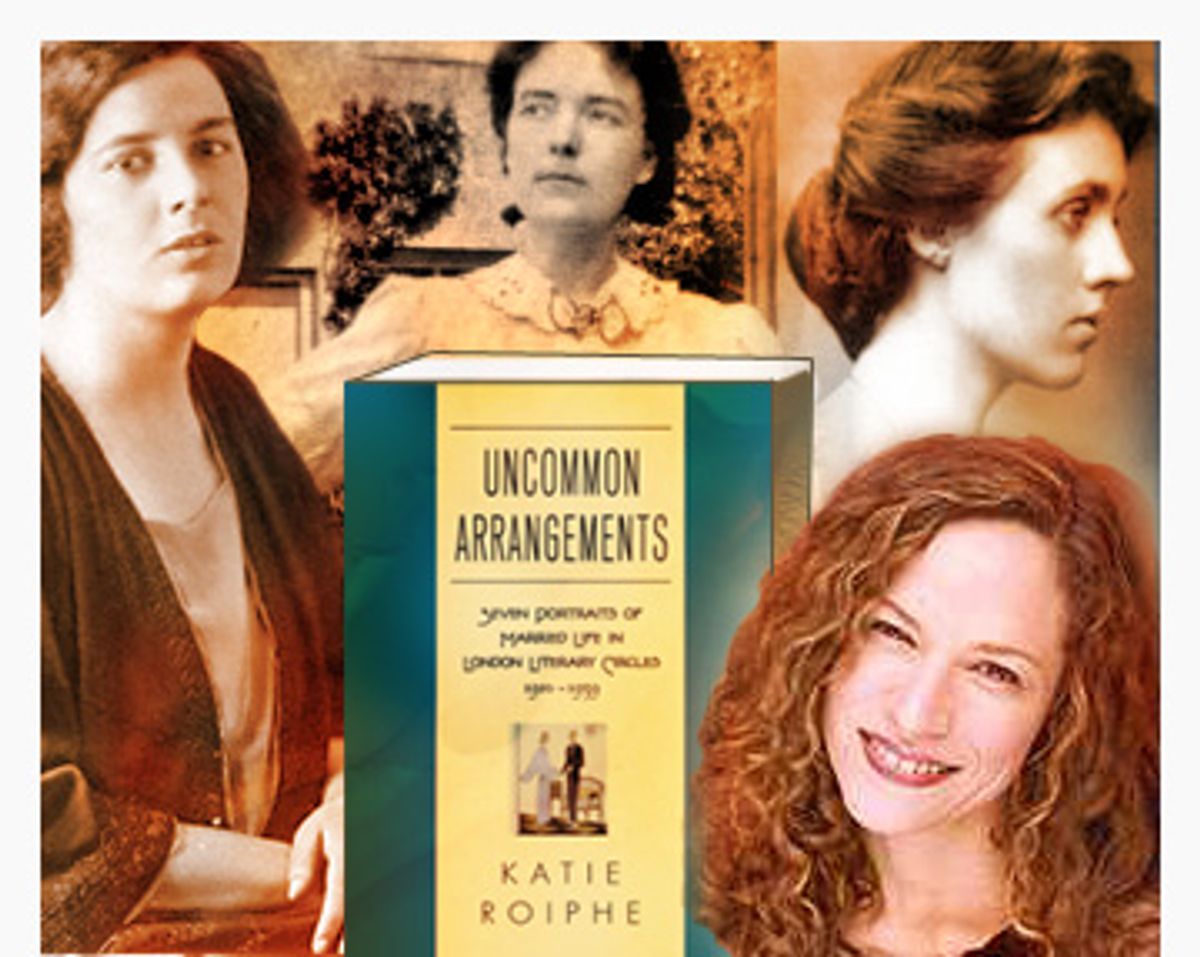

In her new book "Uncommon Arrangements," about the marriages of seven couples on the London literary circuit in the early 20th century, Katie Roiphe describes pacifist journalist Vera Brittain as a woman who "radiated an ambition that made itself felt as nervous charisma."

It was fitting, then, that as Roiphe sat at a Brooklyn cafe on an early summer afternoon, she picked unconsciously at her nails, chewed on a straw until it was ragged, and radiated a frank likability.

The 38-year-old author first made her name as the baby bête noire of feminism with her 1993 screed against campus date-rape activism, "The Morning After." The book made Roiphe, then a 25-year-old Harvard grad and the daughter of feminist writer Anne Roiphe, a child star of sorts, a symbol of the generational rupture in the women's movement and of a post-Reagan conservative backlash among young people. Her I'm-too-sexy-for-this-movement provocation partially inspired Tad Friend to coin the term "Do-Me Feminism" in 1994.

Since then, Roiphe has earned her Ph.D. in English from Princeton, published "Last Night in Paradise" (a lament about how AIDS education was killing America's hard-ons), a novel about the infatuation of Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) with young Alice Liddell, and some contrarian gender journalism, including an Esquire story about how independent women want men to take care of them, none of which has endeared her to the community of left-leaning women in which she was raised. But recently, Roiphe and her targets have made steps toward a tentative rapprochement. The scholarship-heavy, polemic-light "Uncommon Arrangements," is earning raves, including one from Tina Brown in the New York Times. And this spring, Roiphe was named a professor in NYU's prestigious and historically left-leaning Cultural Reporting and Criticism program. It seems possible that after 14 years, this enfant terrible, or her critics, are growing up.

"Uncommon Arrangements," an examination of other people's marriages, steers clear of the kind of autobiographical detail that littered Roiphe's earlier work, but it is infused with what has long obsessed her: the power dynamics of sex and love.

Roiphe said she began her new book in the period after the 2005 death of her father, psychoanalyst Herman Roiphe, and as her five-year marriage to lawyer Harry Chernoff was disintegrating, a time she lightly called "the worst period of my life so far."

In this time of personal calamity, she turned to biographical material about figures who fascinated her, maintaining what she called "an ardent belief that studying other people's lives can help you with your own." The result of her investigations is a collection of satisfyingly detailed, occasionally lurid portraits of the serpentine sex lives of some of Roiphe's heroines, including writers Rebecca West, Katherine Mansfield, and Virginia Woolf's sister, Vanessa Bell.

What did Roiphe learn from snuffling so dilligently through the detritus of glam literary couplings? She was struck, she said, by "how many things happen in a relationship when you're not looking." She mentioned a letter from heartbroken political scientist George Gordon Catlin to his wife, Brittain. "It seems like the kind of letter you'd respond to," said Roiphe, "but according to her own mythology, she gets a stomach ailment, puts it in a drawer, and moves on. I see that happening again and again: You turn away for a moment and this distance occurs without you realizing it."

Despite her interest in the common connubial failure to mind the gaps, Roiphe is convinced that we can learn from these couples the perils of over-communication. "Many people believed you should tell your partner if you're attracted to someone or if you cheat," said Roiphe of the period in which Victorian repression was being frog-marched offstage by free-thinking modernism. "This to me is a really crazy idea." She was also taken by the early 20th-century vogue for mastering emotion with reason. "These people were pioneering relationships where they're going to be equal and control their feelings with ideas," she said, "And of course, that's doomed to failure ... Reason always fails and emotion always wins out in all its most banal forms."

In "Uncommon Arrangements," as in her previous work, Roiphe is an apologist for passion. The notion that enlightened thought could scrub clean the grime of our stygian urges is as much a hoot to her as it was when she scoffed at the idea that education about date rape might help students navigate what she called, in "The Morning After," the "libidinous jostle" of modern life.

The appeal of this stance is clear. Who doesn't want to write off ill-advised moments as the result of irresistible ardor? Of course, passion is also one of the world's great cop-outs, a shrugging off of responsibility, whether for not-quite-consensual sex, unprotected congress, extramarital affairs, sleeping with our friends' boyfriends (to which Roiphe has also admitted in print), or a failure to live up to any of the myriad romantic, moral or domestic responsibilities adults are expected to shoulder.

"I'm always writing about that 'wild unsensible emotion' over all the different ways we try to rationalize it," Roiphe said. "That may be why I find myself where I do today" -- here she gave a self-deprecating laugh.

Roiphe has been torn throughout her career between her wish for more old-fashioned social control and her desire for unmoderated social and sexual indulgence. This split is evident in "Uncommon Arrangements," in which Roiphe is clearly beguiled by the naughty dalliances of her subjects, yet expresses prim approval for marriages that fulfill more traditional expectations. She is also entranced by the attraction of strong women to abusive jerks.

"One thing that interested me was how many strong feminist women like Elizabeth von Arnim or Rebecca West were enchanted with this kind of old-fashioned brute," said Roiphe. "They really wanted a man who was domineering and more powerful. These [expectations] are very timeless."

In "Uncommon Arrangements," Roiphe also returns to another of her favorite themes, assuring readers, in a sentence that could have been the subtitle of "The Morning After," that "where a man has been monstrous, the woman has almost always had some hand in creating her particular monster."

"What you're picking up is my resistance to demonizing men," she said. "I have a definite ideological resistance to placing women in the role of victim, especially when you talk about something as intimate and complicated as their personal lives. I do believe that both people are always responsible, and I know from my own experience with marriage that it's very easy and seductive to see yourself as the victim. To me, there is a moral imperative to resist that story."

This is a tune Roiphe has been warbling for 14 years now, and it surely soothes those men who are sick of being told that sex is no longer theirs to take whenever they want it, that they have to share domestic duties, that they have to wear condoms to keep themselves and their partners safe. Don't worry, her books say. Not all of us want so much from you.

In "Uncommon Arrangements," Roiphe seemingly describes the young Rebecca West, who had an affair and a child with married H.G. Wells, as needy and fishwifey, noting that Wells wanted "someone to care for him ... [while] Rebecca wanted someone to fuss over her." She kvells over Wells' long-suffering doormat of a wife, Jane. Describing her decision to stay with Wells after he had abandoned her and their newborn son, Roiphe writes admiringly, "Instead of responding to her husband's sudden absence with anger, Jane wrote to H.G. a warm understanding letter in which she blamed herself for being too possessive when he left, and set the relationship on its stable new course."

When I told Roiphe that I read this as a celebration of Jane's stoicism and a chastisement of West's demands for respect, she wrinkled her nose and said, "Really? I don't know why it came off that way." Asked if perhaps she was critical of West because she identified with her, she said, "I can imagine myself in Rebecca West's role, and maybe that does make you harder on someone."

Perhaps it's Roiphe's internal contradictions -- that she empathizes with the Rebecca Wests of the world but has made it her life's work to mock their high expectations and point out their hypocrisies; that she cannot decide between her desire for control and her desire for unbridled emotion -- that allow such varied reactions to her work.

"Some people see this book as telling them they should have affairs. Some people see it as a rousing defense of traditional marriage," she said, glad people can find in it what they want. "To me that is an interesting way to write," she said, "as opposed to what I wrote when I was younger, which was more domineering: Here's my idea, you must agree with me. I still like that kind of writing; I teach polemic at NYU, but that wasn't what I was after in this book so much."

Roiphe does teach polemic at NYU, hired as a professor at the school's well-regarded graduate program in Cultural Reporting and Criticism, founded in 1995 by pioneering feminist journalist Ellen Willis, who died of cancer last November. Roiphe's hire in the wake of Willis' death has led to what Alexandra Jacobs described in the New York Observer as "eye rolls" from "a certain social circle" that still views Roiphe as an antifeminist icon and her hiring an insult to Willis' memory. In fact, Roiphe has not technically taken Willis' job. Professor Susie Linfield has been promoted to running the program, and Roiphe is its second full-time professor.

Linfield has some choice words for anyone who questions Roiphe's appointment. "Ellen was completely uninterested in political correctness," she said by phone, adding that it was Willis who had originally hired Roiphe as an adjunct professor. Linfield later elaborated: "Both Ellen and I came out of feminism and the left ... Obviously Ellen was, and I am, aware that Katie does not come out of that tradition -- at all. The fact that we take seriously -- on an intellectual level, and as a writer and teacher -- someone with whom we have real disagreements apparently bothers if not angers some people. Frankly, I find that incredibly dispiriting if not appalling. And frankly, putting on that kind of intellectual straitjacket is exactly what we want our students to never learn to do."

Cultural critics might reasonably consider what it means to have Roiphe teach students where Willis once taught. But not all of them are appalled.

"I think she is not a ridiculous replacement for Ellen Willis," said feminist writer Jennifer Baumgardner, who has been critical of Roiphe's work in the past. "Superficially, sure, it's a total affront. But on another level I feel that Ellen Willis' philosophy about feminism was about not keeping herself ghettoized, because she knew it was through culture that these messages were really going to become transformative."

It doesn't hurt that everyone I spoke to who has been in a classroom with Roiphe -- Salon hires many of its interns from NYU's cultural reporting program -- raved about her teaching. "Katie's students adore her," said Linfield.

When I asked Roiphe -- who has taught a class called A Short History of Women Critics -- where she would place herself in the history of feminist writing, she blanched briefly, assuring me that she doesn't teach her own work, before answering.

"I often teach one of my favorite essays, which is Joan Didion's 'The Women's Movement,'" she said. "As I say to my students, there are some people who go to the barricades and there are some people like Joan Didion who stand at the cocktail party making fun of the people who go to the barricades. It's two different temperaments, and they're both admirable, and I would just be the person at the cocktail party making fun of the people at the barricades."

It's not lost on Roiphe or her critics that her mother was one of those protesting. "My mother was different," said Roiphe. "She was at marches with picket signs. I admire that feminist tradition as well, and feminist writing in a less ironic and satiric spirit. But there has to be room for both of those things. When my first book came out, there wasn't."

"The Morning After: Sex, Fear, and Feminism on Campus" (the "on Campus" part was dropped for the paperback edition to give it that extra backlash-fabulous oomph) was polemic, as Roiphe now admits, though she denied it at the time. In it, she attacked the anti-rape activists then advocating for blue-light safety systems, date-rape education, and holding Take Back the Night rallies, all of which Roiphe saw as fear-mongering that cast coeds as modern-day Clarissas, all weak and wobbly and awaiting their defilement in the hands of their Delta Tau Delta Lovelaces. Roiphe's feminist proclamation was that women loved sex too, and that "rape" was often simply subpar sex.

I was a college freshman the year that "The Morning After" was published, at a Midwestern Big Ten school. I lived in a dorm in the middle of the fraternity quad, on an all-female hallway on the ground floor. By the end of the year, I knew an awful lot of people who had had varying degrees of what Roiphe would call "bad sex" and what some of them called "rape" -- though never officially. Of all the women who felt that they had had sex against their will, I did not know of a case of date rape that was reported during my freshman year. I was furious at Roiphe, for sending a message to young women that all sex was OK sex, and that they were probably complicit in any violent sexual experiences they might have had. In my freshman year, Roiphe's book was jauntily kept in some fraternity houses, a talisman against the potential succubus of the date-rape accuser.

Roiphe based a good deal of her argument on anecdotal evidence that did not hold up under scrutiny, and on her dislike or skepticism of the women who got up at Take Back the Night rallies to tell their stories. The book was widely attacked by feminists like Gloria Steinem and Katha Pollitt; the latter carpet-bombed Roiphe's reporting in a review in the New Yorker.

In "The Morning After," as in her current book, Roiphe (less subtly) trafficked in some of the same appealingly retro complaints about women: that they are whiny and hypocritical. It's clear that the kind of female strength she admires is derived not from the courage to speak up about mistreatment but from stoicism: the willingness to suck it up, put your clothes back on, and chalk it up to the wildness of unsensible emotion. Weakness is the quality she most deplores, and "victimhood" is her favorite verbal spear.

Some may consider Roiphe an architect of the destructive schism between those in the women's movement who perceive themselves as "victims" and those who believe that the word creates an enfeebling paradigm. In fact, Roiphe merely, and possibly unknowingly, served as a megaphone, amplifying some of the battles that had raged for decades between the varied interests joined beneath the large umbrella of the feminist movement. Roiphe's NYU predecessor Willis had made her own name years earlier by opposing anti-pornography advocates like Catharine MacKinnon. Roiphe's success was in playing on the public's notion that feminism was threateningly monolithic and in casting herself as the lone dissenter storming its walls -- strong, sex-loving and unplagued by the fragility to which she is so allergic.

"She is definitely guilty of 'Well, I don't have this problem' thinking," said the writer Baumgardner. "She seemed to have no understanding that not everyone was her, and she may have been very unique in being so resilient or so lucky that she was never raped."

Baumgardner acknowledged her youthful abhorrence of Roiphe's work. "Initially I was like, 'She's the Antichrist," she said. "I had had a lot of personal experience around [rape] and I was offended by what she wrote. But I think I'm realizing that there was a gift in that book: the message that our generation could be feminists but could evolve and figure it out for ourselves. I came not to be threatened by what she had said, but to see it as an invitation to question things and think independently and call that feminism."

"I still believe everything I wrote in that book," Roiphe said, adding, "I wrote it when I was 23, and were I to write it now, I would write it differently. It's definitely the book of a very young person."

But the victimization-averse Roiphe is clearly still bristlingly pissed at her early critics. When I brought up Pollitt's New Yorker review, she said, "It was name-calling. She wrote, If Katie Roiphe was your friend, would you tell her if you were raped? ... It was a pretty personal attack."

Pollitt responded, "If you put yourself out there and write a controversial book, not everybody is going to love you, and her book was attacked very much on its content." Since Roiphe used the fact that none of her friends had been raped as evidence in her argument about the overblown nature of campus rape claims, Pollitt said, then it was not inappropriate to wonder if perhaps her friends had not confessed their rapes to her.

Pollitt's criticism, said Roiphe, "was like playground stuff ... I really encountered that when I wrote that book -- the schoolyard stuff. I would go into a taping of a radio show or a TV show, and no one would talk to me. You'd feel that atmosphere of the mean girls. I definitely experienced that aspect of feminism."

Of course, there are mean girls who write negative reviews about you in the New Yorker and there are mean girls who sneer at the rape testimonials of young college women, which is what Roiphe did, and no doubt accounts for some of the treatment she received in kind.

As it happens, I was the kind of mean girl who once refused to shake her hand, 10 years ago, when I was working in an office where she came in for a meeting. When I told her this, she looked only mildly surprised.

"George Will calls that book a barnburner," said Roiphe. "I don't regret that I'm the person who would write a barnburner. It's not really where I am now in my life. It's hard to be that person: You're talking about not shaking my hand. There were a million people who were not shaking my hand. People write to be loved, so it's distressing to write and be shunned, but obviously there was something in me that was drawn to that."

Roiphe doesn't disagree with critics like Deborah Siegel, whose new book "Sisterhood Interrupted" charges that Roiphe was partially responsible for the rupture between her mother's generation and her own. "I have to say my mother fully supported all my views," Roiphe pointed out. "Possibly because, you know, what choice did she have? I see my work in continuity with people like Betty Friedan and with what I see as the deeper purpose and real mission of feminism. But it was certainly a rupture with the personal-is-political, a woman-needs-a-man-like-a-fish-needs-a-bicycle, Gloria Steinem type of feminism."

If she sees her work in line with Friedan's, she might consider a paragraph in the preface to "Uncommon Arrangements" in which she writes about the "dreary debates about marriage" that can "be entirely summed up in the question of who has cleaned up the smattering of Legos scattered across the floor of the baby's room." Roiphe wonders, "Why should there be so much fury attached to the most insignificant drudgeries of domestic life? ... Why when women have so many choices, are we still as angry as gloved suffragettes hurling bricks through windows? What unmitigated bliss, one does wonder, were we expecting?"

Here still is Roiphe's seductively low-pitched murmur, a signal tuned precisely for the ears of men who are sick of being hassled about the fucking Legos already. "This endless conversation about who is doing what in terms of house responsibilities and all that," said Roiphe wearily. "To me it goes back to that great Joan Didion essay: We are mired in the trivial."

But, I replied, citing Linda Hirshman's "Get to Work," which argued that the division of domestic labor is precisely where feminism has failed, we worry about the Legos because the person to whom it falls to pick them up (or to cook, clean, do the laundry and childcare) is the person who has less freedom to make money and live an independent life. And that person is often a she.

"How lucky we are that that should be our biggest issue," deadpanned Roiphe. "You'll find that it actually doesn't take that long to pick up the Legos. What really takes a long time is the three hours of rage and resentment about it."

As she talked about these issues -- even in the context of her new book, set a century and a continent away -- it's clear that Roiphe is, as she has always been, an embodiment of a particular kind of irritant: the kind that chafes at women unsure of how aggressive and polite, how sexy and militant, how earnest and ironic to be in this age when freedoms may be ours, but at a price that can still be painful. She has mellowed, certainly, in the 14 years since I first picked up her police siren of a book. Her writing has blossomed too; she shares a damnably silver tongue with fellow feminist bugaboo Caitlin Flanagan. Or perhaps it's her critics, some of whom developed our own sensibilities in reaction to her work, who have mellowed in our reaction to her.

As "Sisterhood Interrupted" author Siegel told me, "'The Morning After' provided the stimulus in some of her peers to commit themselves to feminism." Siegel, who was in graduate school in 1993, said, "She's the reason I do what I do. I was locked in the ivory tower and here was my peer talking about how women are no longer victims because she didn't know any. I found that insanely infuriating. I figured if Katie Roiphe was out there making these arguments, I wanted to write for a wider audience."

Katie Roiphe was probably the reason I do what I do, too. I asked her if she was aware, or felt any accomplishment, in having re-energized a feminist movement, or energized a new generation.

"I don't know if the people I was re-energizing should have been re-energized," she said with a dry laugh. "But to write something where somebody says you're the Antichrist ... I'm not above thinking that that's an achievement itself."

Shares