The women of Iran have jolted me awake from my cable news coma. So many of the protesters are young and female like me but display a courage I have never known -- clasping rocks in their fists, kicking at baton-wielding policemen and, in the case of Neda Agha-Soltani, dying on the streets of Tehran. Judging from the flood of "I am Neda" T-shirts and tweets, I'm hardly the only one feeling not just powerful admiration but identification with Iranian women.

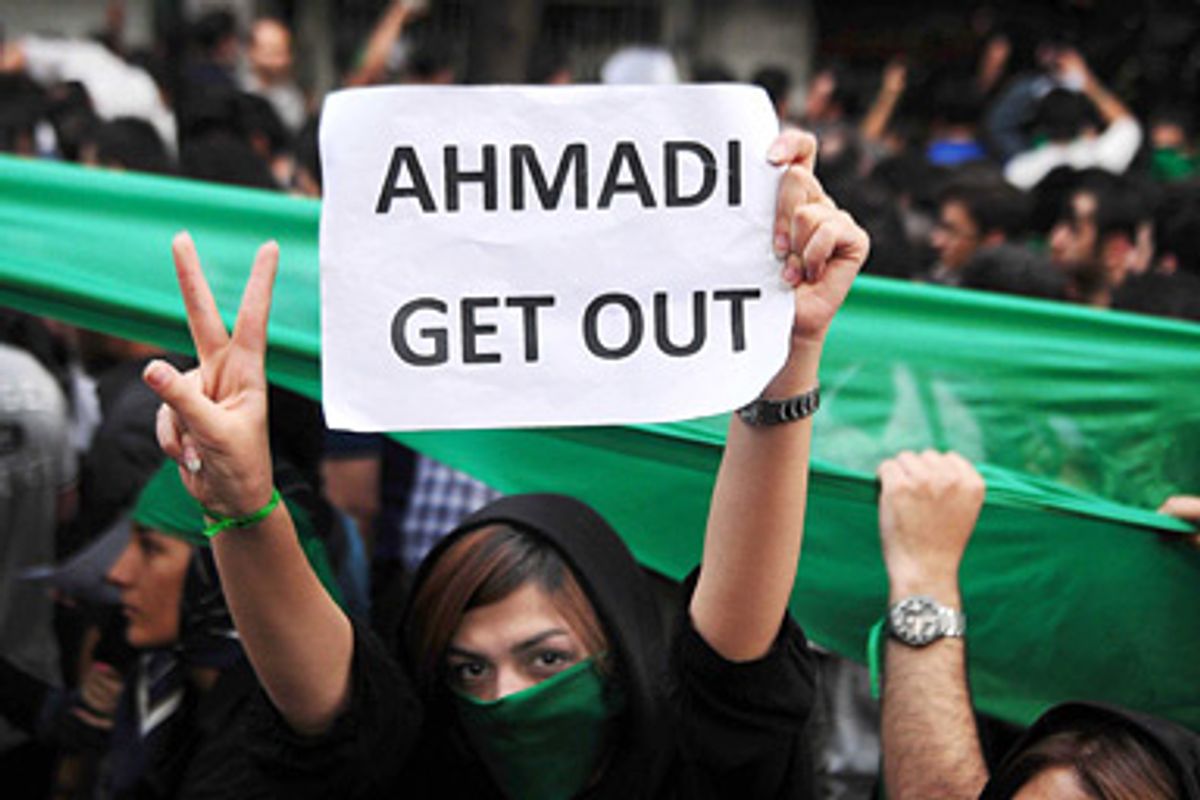

But every time I have a fleeting thought of turning my Twitter icon green or changing my Facebook location to Tehran, I think of the guy who sports a Che Guevara T-shirt but can't locate Cuba on a map, or the lady who has a "Free Tibet" bumper sticker and no sense of what the country needs to be freed from. It's easy to become a caricature of empty activism, especially when you're physically removed from the fight. The sneaking suspicion that many of us are in some ways emotionally co-opting the movement is only reinforced by the surprise so many have expressed at the images of these strong Iranian women fighting, and dying, on the front lines with men.

It's not the least bit surprising to anyone who knows anything of Iran and Iranian women. Perhaps you've heard the talking heads on TV refer to the female activists as "lionesses," but that nickname, "shir-zanan" in Farsi, has been used for Iranian women since long before the current revolt, and for good reason. Marsha Mehran, a novelist who was born in Iran, says that the view of women in Iranian society is similar to the stereotype of the strong Italian matriarch. "You would have to meet my mother and grandmother, then you would understand," she tells me from her home in Ireland.

It isn't just cultural lore, though: Women have been extremely politically active in the country for quite some time now, and many Iranians are amused, quite frankly, at the West's sudden revelation that neither chadors nor head scarves snuff out the fire in women's bellies. "This isn't new. This is only the first time that you've been aware of it," Hamid Dabashi, a professor of Iranian studies at Columbia University, tells me with a good-natured laugh. Women were essential political organizers as far back as the 1905 Constitutional Revolution; they also fought and died alongside men in the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which might not have happened without their help.

Since then, women have rebelled in deceptively superficial ways. Post-revolution, many began pushing the bounds of the new Islamic state's moral fabric, both literally and figuratively. The small silk scarves, bright nail polish and dramatic makeup that have become emblematic of the protests are a direct challenge to the official dress code. "It was the way for women to protest since the '80s," says Marina Nemat, author of "Prisoner of Tehran," a personal memoir about being imprisoned, tortured and nearly executed in Iran. "You might be arrested, you might get a few lashes, but you would be back on the streets a few days later doing the same thing." Just a few lashes. Is it really any wonder Iranian women have displayed such daring in recent days? Azadeh Moaveni, author of "Lipstick Jihad," recently wrote in an article for the Daily Beast: "One reason why young women seem so bold when taking on the police and Basiji at protests is that they've had years of practice." In Iran, women soon learn "that meekness [leads] only to victim-hood," she explains. In other words: Don't just stand there. Collect rocks. Throw them.

Women's sartorial protest, along with grass-roots feminist activism against stoning, honor killing and polygamy, has belied the regime's "air of invincibility," says Abbas Milani, director of Iranian studies at Stanford University. "When the history of this period is written, women will emerge as the vanguard of this struggle." It's a struggle, and frustration, that has been building for decades. Women turned out en masse to support the Islamic Revolution because they believed it offered hope of greater freedom and equality. The great irony was that the actual result of the revolution they helped realize was a draconian rollback of their rights. Now, 30 years later, after the disputed loss of a presidential candidate who is against violently coercing women into veiling and is married to an educated and opinionated woman, whom he dares hold hands with in public, they believe that they have been cheated, yet again. Hell hath no fury like three decades of women scorned.

Today's protests are different, of course -- namely because the world is watching. "Now, all of the blood that went unnoticed is coming to the surface," says Nemat. "At least finally there is Neda, someone we can point to and say, 'Look at what happened to her,' and then, 'This happened to thousands before her.' She is not the first and she won't be the last." It isn't just Neda, either. In general, the images of Iranian women -- young and old, clad in chadors and scant designer scarves -- have been a valuable emotional bridge for men and women alike. They're more sympathetic figures not only because, of course, many consider them to be the fairer sex, but also because of the way the Islamic regime has tirelessly targeted women.

There's always the danger of taking that sympathy too far, though. "There is a bit of neoliberal rhetoric. You know, 'We need to save these women, they're repressed and don't know it,' which is not the case," says Pardis Mahdavi, author of "Passionate Uprisings: Iran's Sexual Revolution." "These women are finding agency in all sorts of pockets, in all sorts of ways." (She really does mean all sorts of ways: Her book unveils Iranian youth's sex parties and anonymous hookups.) It's also easy to paint our own political ideals over the more nuanced and complex ones of Iranian protesters. This goes far beyond gender and simply removing the veil. What we're witnessing right now is a broader social movement that was made possible by decades of feminist activism, from women and men. "We can identify, but because the situation is so much more complicated than we realize, we really can't understand," she says.

I've read enough Iranian feminist texts, memoirs and poetry to know just how little I understand, how it's impossible for me to see the protests through anything but my own myopic American lens and how these women are fighting their own fight, and have been for some time. As Kate Harding recently wrote in Broadsheet, "I am not Neda" and I'm tremendously lucky for that. But it's impossible to deny the stirring in my belly when I see these "shir-zanan." Abbas Milani of Stanford kindly assures me that this is only natural, especially for young feminists like myself: "They have compassion for these women who are trying to break, not the glass ceiling, but the hardcore steel ceiling," he says. "They see their sisters there."

Shares