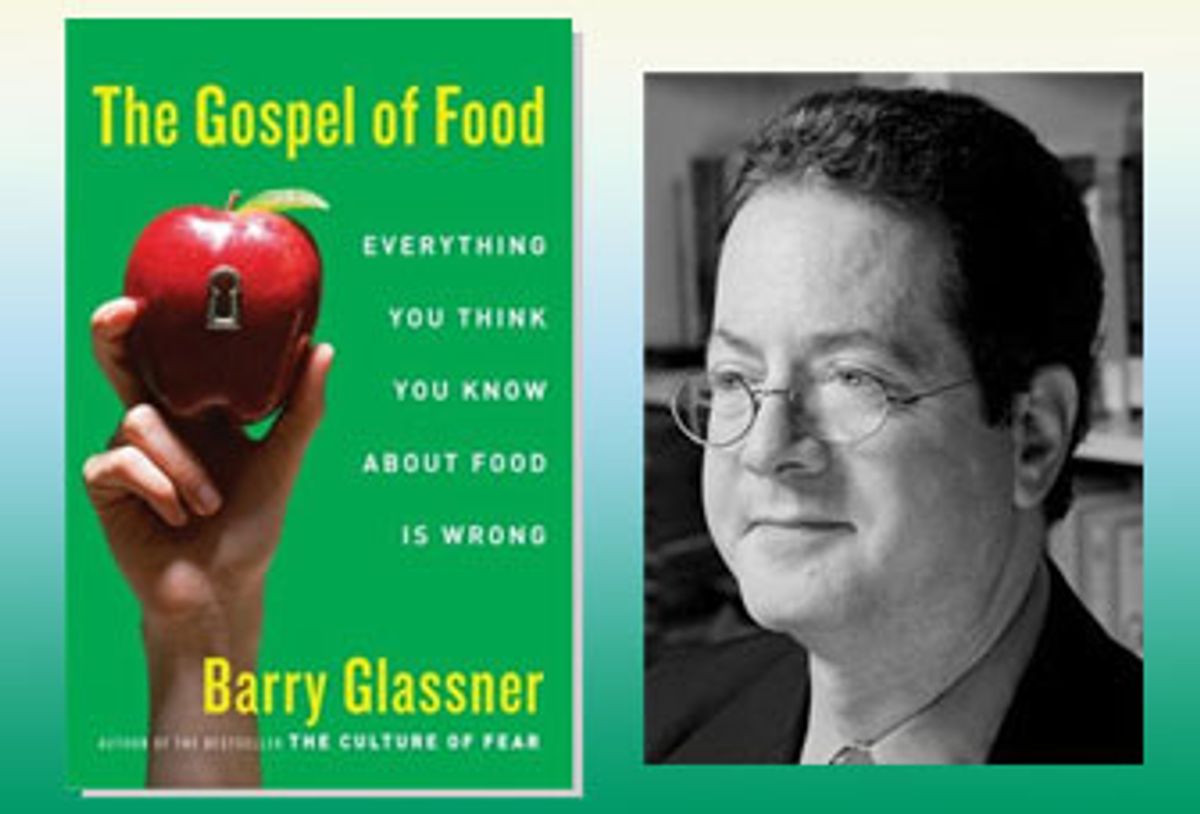

America's food enthusiasts may find it hard to place the name Barry Glassner. He's not a television chef, or a restaurant critic, or a diet guru. Indeed, the University of Southern California sociologist is known primarily for his best-selling 2000 book, "The Culture of Fear," a dissection of the anxious underpinnings of the American psyche. It's a subject that might seem to have little relevance to the dinner table, but Glassner begs to differ. If his latest book, "The Gospel of Food," makes one thing plain, it's that few topics generate more worry among Americans than our breakfasts, lunches and dinners.

Glassner relishes debate, and "Gospel" -- which sports the insistent subtitle Everything You Think You Know About Food Is Wrong -- takes on nearly every sacred cow of contemporary food culture. High-end restaurant reviewers, eaters seeking "authentic" ethnic eateries, organic converts, local agriculture proponents, and fast food's detractors all receive a methodical interrogation of the accuracy of their claims.

But while Glassner examines nearly every issue populating the food landscape, "Gospel" shines brightest when he turns his gaze to two that are frequently absent from it: poverty and class. Though he places himself in the company of industrial food's most vocal critics, like Michael Pollan and Eric Schlosser, Glassner sets his sights on them, too, questioning the very journalists, writers and advocates who claim to speak truth to power. The problem, he argues, isn't that the Pollans and Schlossers of the world are wrong, but that they're not exactly right, either. To get to the bottom of something as complicated as America's obsession with fast food -- a category of dining, he points out, that offers low-income families a clean, affordable and convenient meal in ways that anti-industrialists seldom acknowledge -- he'd rather engage with the complexity of the matter than reduce it to sound bites.

Glassner manages nonetheless to come up with a few maxims of his own: Restaurant reviews rarely reflect the experience of average diners -- because most top-notch food critics, disguises or no, are rapidly recognized by chefs, who heap special treatment upon such visitors. The American family meal is not dead -- in fact, one of the most oft-cited studies in this vein, which attributed the success of a cohort of National Merit Scholars to eating regular family meals, never existed. And obesity is not a simple problem of eating less and exercising more; its prevalence among the poor is likely attributable to bingeing brought on by a periodic scarcity of food -- not mere ignorance.

Still, Glassner's laundry list of inaccurate spins should not be taken as a humorless diatribe. "Gospel" is also sprinkled with a passionate eater's enthusiasm for cuisines both street and haute. And the extensive journalistic and academic research around which the book revolves is bookended by discussions of the pleasures of food, ranging from Glassner's own horror at a birthday cake devoid of wheat, sugar, milk and eggs to his hearty enjoyment of a rib joint in south Los Angeles. The point, says Glassner, is that a mix of American puritanism and health obsession has stripped the pleasure out of many Americans' meals -- with little to show for it.

Salon recently caught up with Glassner by phone to discuss why trans fat bans aren't all they're cracked up to be and how your mom's advice about food may be the best you'll ever get.

How did the idea for this book come about?

When I finished my previous book, "The Culture of Fear," it became obvious to me that I had missed one of the biggest fears in American culture, which is that many Americans are afraid of just about every kind of food for one reason or another. So that's what got me started. And secondly, I myself am a big food enthusiast, I love eating diverse foods in very diverse sorts of places, so this gave me an opportunity to do that -- and make it tax deductible.

Was there a specific incident that made you recognize Americans' fear of food?

It's the one I start the book with: I was at this birthday party for a child, and I took a bite of the birthday cake and my tongue stuck to the roof of my mouth. The parents were so proud that they had provided this "healthy" birthday cake, because it didn't have anything in it that would make you want to eat a cake. It didn't have eggs, or milk, or wheat, or butter, of course, and it didn't have any sugar because, of course, that could kill you immediately. I started thinking, "It is bizarre that this is what we've come to," and that was kind of the turning point.

You work hard to debunk studies, pulling out ones that contradict commonly held assumptions, or ones that are based on one or two earlier studies or a misrepresentation of findings. What was the most surprising discrepancy you came across?

I guess I'd pick that National Merit study, which supposedly showed that the common denominator among a cohort of National Merit Scholars was that they all had regular family meals. It's mentioned all over the place, when in fact it never existed. The whole truth about family meals was a surprise; I had thought that the family meal was a thing of the past, when in fact families eat together at about the same level as the 1950s.

Food and obesity are such hot topics right now, but you take aim at some very well respected writers on the subject. For instance, Greg Critser's book "Fat Land" basically argues that we need to be hardcore about the idea that it's not OK to be fat and, really, lines must be drawn in the sand. But my sense is that you come at the problem from a different angle.

I think there's a lot of merit about Critser's book and I'm also critical of parts of it. So when he says that the rich are more insightful about what to eat, that concerns me. I think that if we want to understand why it is that people of lower income are more likely to be overweight or obese, to simplify it to a moral condemnation is not a wise way to go. The very notion that wealthy Americans are constrained in their consumption patterns is absurd. Witness their SUVs, their oversize homes. It's fashionable for the wealthy to be thin and eat particular sorts of foods that are on the approved list, but let's not give them undue credit for that, especially at a time when you can go to most any high-end restaurant and get very high-fat, high-calorie meals.

If you want to understand why people of low income tend to be more overweight and obese, it's a complicated story. But we shouldn't leave out the effect that food insecurity itself has; in the book I go into this in some detail, but basically there's a parallel pattern to binge eating, where people who periodically run low on food resemble people who are on diets. When food stamps run out, or the kids' medical expenses take precedence, or the local food bank shuts down or runs out of food, you're not going to eat a lot. And when food becomes available again, you binge.

We know that this pattern, this binge pattern, contributes to overweight and obesity. Yet we've come to have this odd notion that it's what people eat, it's what low-income people eat, rather than what they don't eat, or when they don't eat, or which options are not available to them, that explains their weight. And moreover, to the extent that heavy people are stigmatized in this country -- as they very widely are these days, including by people who see themselves as liberals or progressives -- the more we're heaping on further dangers to their health because we know that discrimination itself is a predictor of ill health.

What do you hope to add to the debate?

What I'm hoping is that my book will really open up people's eyes to thinking about some of these topics in ways they haven't before, and in particular, it will make people more open to greater diversity in their diets. I think the good news about this food-obsessed age of ours is that there's a lot of variety out there that wasn't there before. Many Americans take pleasure in exploring new tastes. But at the same time, vast segments of the population greatly restrict what they eat, whether it's because they're on a low-fat diet, a low-carb diet, they shun places that are too popular, or only go places that are very popular. For a whole range of reasons that I write about, they're very restricted, so I think there's a lot more opening up to be done than has happened so far.

What's your sense of how many people are really on these diets? I certainly don't know them -- but then, I'm in Brooklyn.

Let me put it this way; I think that the dietary regimens people put themselves on vary and contrast with one another but in many cases are very restrictive, whether it's veganism or the Atkins diet. And part of what I find interesting is that in each of these cases, followers believe that their diet is miraculous, almost.

My own view is eat and let eat. I'm perfectly comfortable with people following an Atkins diet and eating meat with every meal, or a vegan diet and never eating any animal products. What I'm uncomfortable with are the exaggerated claims that they make, that a meatless regimen can prevent most every serious malady from heart disease to world hunger, or that following an Atkins diet is a magical potion for longevity and weight loss.

I think there are millions and millions of Americans who try to follow one version or another of the "gospel of naught," which is this notion that the worth of a meal lies primarily in what it lacks rather than what it has. So the less sugar, salt, fat, calories, preservatives, animal products, carbs, additives or whatever the person is concerned about, the better the food. And this seems to me a quite curious notion that's worth a lot more attention than we've given it.

While I was reading the book, I couldn't help feeling a little overwhelmed by all the ways in which commonly held beliefs about what's healthy -- whole grains, low fat, being lean -- were being called into question. And the big question I came away with was: What do I do now?

I think that there is a basic precept that serves very well, and that's to eat well and enjoyably and moderately over the long haul. I certainly do not advocate that eating a large quantity of any of the substances that are currently considered bad or unhealthy would be a good idea. The kind of diet that Morgan Spurlock went on in "Super Size Me" is obviously going to make you sick. But so would eating three meals a day of boiled broccoli. So, I think that it's certainly wise to be concerned with eating well and eating moderately and taking into account the sorts of advice that generations of mothers have given, and occasionally fathers. Eat your veggies, eat your fruit, and don't overdose on sweets. So, in no way am I advocating that we should replace the gospel of naught with some kind of absurd diet that would go in the opposite direction.

What about people who say, "Oh, I'm going to treat myself," and end up treating themselves almost daily. How good are Americans at eating moderately?

I think that one way that the food industry is brilliant is in picking up on the bipolar approach to food that we have in this country where we think that certain foods are good or bad, or sacred or profane. The food industry will sell us foods that make us feel like we've been good and righteous and then they'll say, often in so many words, "Now that you have been good you can be bad and buy this other product." And they win both ways.

When you listen to a lot of people talk about their meals, they use words like, "I've been bad," if they order a creamy dessert at a meal. Or, "I've been good," if they stay on their diet. The key motivator there is guilt and the avoidance of guilt. And it applies not only to ourselves, but to other people. So many Americans take as a literal truth the old maxim that you are what you eat. We believe that we can tell a lot about a person by what he or she eats when really what we're expressing are prejudices.

In the book I talk about one of my favorite studies, which was a study where students were shown photographs of people their age and researchers told one set of students that the people in the photographs ate foods like whole wheat breads and chicken, and they told another set of students that these same people ate hamburgers and French fries and hot fudge sundaes. And in fact, the students had been shown the same people, but they ranked them very differently based on what foods they'd been told they ate; ranked them as more or less likable, more or less attractive. I think that really goes to a deeply ingrained prejudice in society.

Where does that prejudice come from?

I think it comes from our religious backgrounds, which we've taken in this secular direction. In both Judeo and Christian traditions, diet is emphasized and special foods are emphasized. In traditional religious teachings it's very specific; Judaism and Islam prohibited pork, Catholicism decreed fish on Friday. Today we have more secular versions of it, and the response that comes out in an experiment like that is an example of it. People engaging in elaborate rituals to prepare meals; that's another part of it, as is the kind of godlike status of celebrity chefs. I take the titles of my books very seriously, and it was after a lot of thought that I decided to call it "The Gospel of Food."

I was interested in how you classified different groups of advocates and writers as "food adventurers," those who seek out authentic foods, or "adherents to the gospel of naught," who seek health. How would you classify yourself, and what are you seeking?

I'm very much a food adventurer and a little bit of a foodie. I love expanding my horizons and exploring different cuisines. I'm truly delighted when I'm enjoying ribs from Phillips Bar-B-Que here in south L.A. -- and at the same time, I've had some of the most wonderful moments of my life at meals at some of the top restaurants in the country, at places like French Laundry and Daniel. So, I'm kind of odd in that regard.

Food adventurers can be annoyingly focused on finding undiscovered places, but aren't most just saying, "Go out, and eat foods that aren't necessarily in the mainstream"? What's wrong with that?

I'm very enthusiastic about the food adventurers but, as with every other group I discuss in the book, you get a substantial subpopulation of them who just go to extremes or limit what they consider acceptable. In their case, the limits often revolve around the notion of authenticity, and that's a very difficult notion and in the end not terribly helpful. I am critical of food adventurers who dismiss out of hand mainstream reviewers of the sorts of places that they go, who think that if the reviewer for the Village Voice or the L.A. Weekly discovered a place and liked it, why would you go there? Their point is to go only to places people either wouldn't know about or wouldn't like. When, in fact, there are some great food critics out there, who specialize in the sorts of places food adventurers like to say they discovered.

You take to task one of the more popular ideas among socially conscious foodies like Michael Pollan, which is that America's food is artificially cheap and we should be paying more to help make it possible for workers to earn better wages.

In my mind, you're raising a couple of different issues. It became evident to me in doing this research that the official dietary guidelines are just that. They're guidelines for most of the population. But they're not for the poor who have to rely on programs that are required to comply with them. Programs like school meal programs and government-run hospitals, and Women, Infants and Children are required to comply with the Department of Agriculture's dietary guidelines -- and that's one example of many I uncovered in the present and the past, where the poorer you are, the more likely it is you will have food regulations imposed upon you. That's not to say these regulations are bad overall, but we should look at who's affected and in which ways. We should do that as well when we criticize eateries that provide low-cost meals to people on limited income. The fast-food industry deserves a lot of criticism and I level it in the book, but at the same time, to be able to get a complete or nearly complete meal for a few bucks, with distractions for the children thrown in at no extra cost, is not in itself a bad thing. And until those of us on the progressive side of the political spectrum have real alternatives in place, we'd be well advised to look at the good as well as the bad.

I'm certainly critical of the political right for its opposition to minimum wage and various labor laws, but when I see the left focusing so heavily on symbols, rather than on actual conditions, it concerns me. I see relatively little organized attention to hunger, for example, relative to, for instance, the kind of effective and organized campaigns against particular types of foods, like trans fats. When somewhere around 35 million to 40 million Americans are facing hunger every year it seems to me that that would be the top priority of any reasonable food activist. The ban on trans fats may be a good thing, but should it be the first thing? Should it take precedence over much more pressing food issues like hunger in the city, or the availability of fresh foods to the poor in the city? No, not for one minute.

Shares