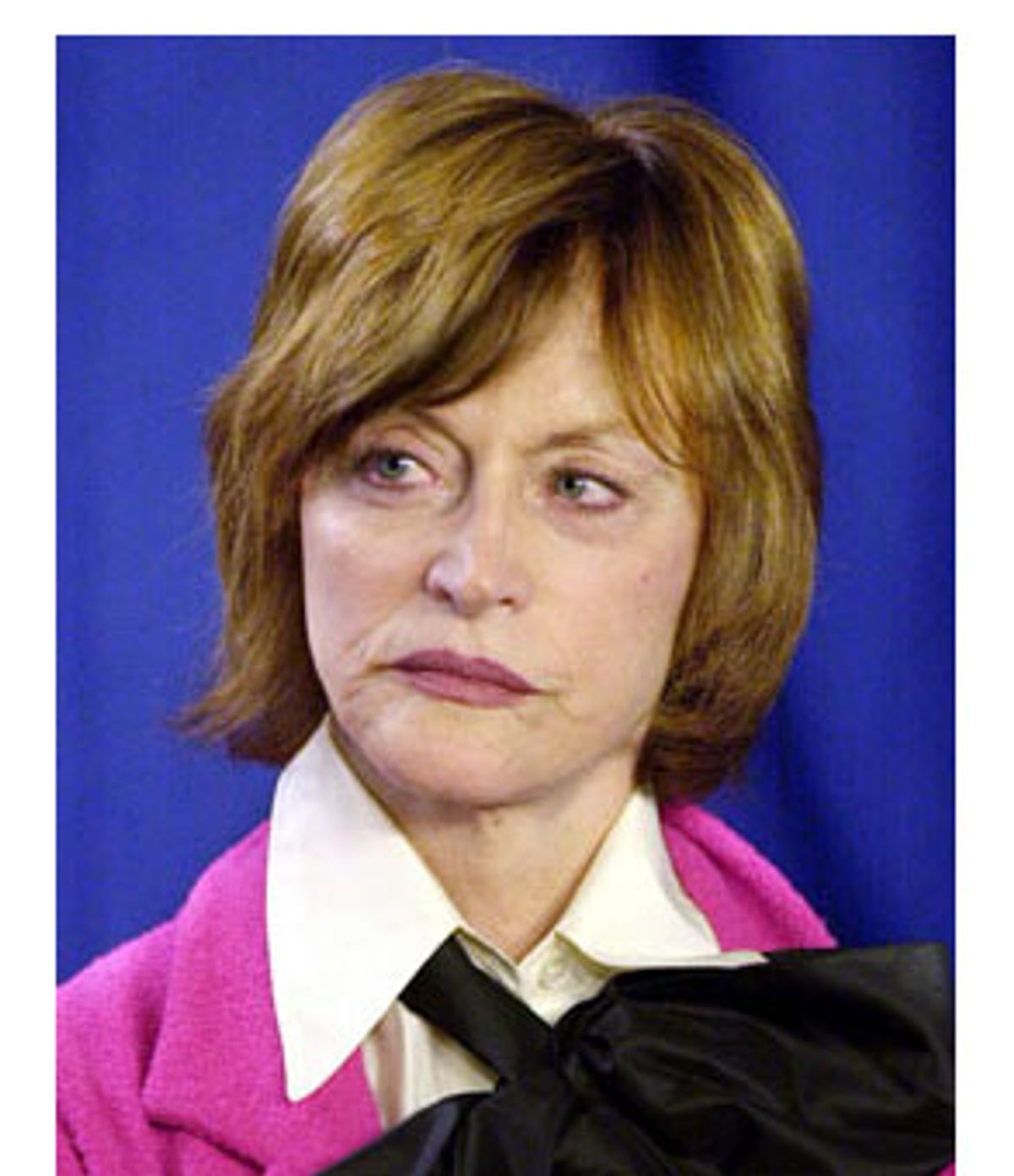

On Wednesday, advertising goddess-turned-State Department undersecretary for public diplomacy Charlotte Beers appeared at Washington's National Press Club to explain how she was selling America to the Muslim world.

The former head of Ogilvy & Mather and J. Walter Thompson, Beers was sworn in at the State Department on October 2, 2001, just three weeks after the Sept. 11 attacks, and charged with polishing the U.S. image abroad. Her message more than a year later: Things are going just fine. Of course, her appearance came the same week as new reports that the Defense Department was planning a so-called "psy-ops" campaign -- a psychological operation relying on propaganda and manipulation -- to sell America's story in allied and neutral countries. That seemed to suggest some lingering worries about the American image, even among friends. But on Tuesday, President Bush disavowed such plans, so officially at least, Beers' mission is the only game in town.

According to Beers, America's information offensive is off to a grand start, putting out messages that are "believable and always true and accurate," she says. One of her first salvos was a series of mini-documentaries about happy American Muslims, designed to show Muslims abroad that the war on terror isn't a clash of civilizations. The films were part of a broader U.S. propaganda campaign that includes Radio Sawa, a station broadcasting Arab and American pop interspersed with pro-U.S. news bulletins, junkets to show America to Arab journalists, and government-published books like, "Iraq: From Fear to Freedom."

Much of the material is aimed at showing Muslims that Americans are just like them -- hence the commercials in which American Muslims rhapsodize about the support and opportunity they've been given in the United States. The ads show Muslim paramedics, scientists, teachers and bakers talking about the freedom and tolerance they enjoy in America. One woman tells the audience that in her neighborhood, all the non-Muslims share her strong family values.

Beers pointed to a survey showing how people in various countries ranked things like faith, family and learning. In the United States, faith was ranked 5, while in Saudi Arabia and Indonesia it was No. 1. A note off to the side of the chart indicated that the godless French ranked faith 42. "We're much closer to our Arab friends than to some European countries," she said. "But there's a gap between perception [and reality] -- that's a communication bridge we need to build."

That was the thrust of her talk -- that anti-Americanism would dissipate once people realized what America is really like. To that end, she said, one of her department's next projects is an "America room" that will use "virtual reality technology" to recreate American streets and other quaint scenes. The room could be put in shopping malls or "on a bus and rolled around," to show those who can't manage a visit what life in the U.S. is all about.

Midway through her talk, four protestors took to the stage chanting, "You're selling war, but we're not buying!" They were quickly escorted from the room. As they left Beers said, "I should point out to those young women that in Iraq they wouldn't have stood a chance of walking out freely."

But the protesters aren't the only ones who aren't buying Beers' message. Experts who follow the Arab press say Beers' ad campaigns are regularly mocked and derided in the Arabic media. "The premise of U.S. propaganda in the Middle East is that Muslims and Arabs are idiots -- simple-minded, feeble-minded idiots," says As'ad AbuKhalil, a research fellow at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of California at Berkeley and the author of "Bin Laden, Islam and America's New 'War on Terrorism.'" "Arabic newspapers crack jokes about these ads all the time."

And the State Department's exchange program is subject to profound suspicion among its target population, he says. "I get 10 Middle Eastern channels. If journalists sound even a little moderate, they are often pressed, 'Have you been to the American program?' There's so much pressure for people to prove their distance from the United States government because of the low regard with which it is held throughout the Middle East."

Mohamad Wahbi, a prominent Egyptian journalist, agrees with AbuKhalil's assessment. He was recently lecturing at universities in Cairo, he says, and students were hostile simply because he works in America. These same students listen to Radio Sawa for the music -- but switch it off as soon as the news segments come on. "Everyone in the Arab world knows Americans are very good at propaganda and they will not be taken in by it," he says.

Wahbi attended Beers' briefing, which he saw as simplistic and one-sided. "They're not going to sell America to the Arab world the way you sell any commodity," he says.

In fact, says Sheldon Rampton, editor of the quarterly magazine PR Watch and coauthor of "Toxic Sludge Is Good For You: Lies, Damn Lies and the Public Relations Industry," when people realize they're being manipulated, their resentment compounds any initial negative feelings they might have had. In "Toxic Sludge," Rampton and coauthor John Stauber wrote about a P.R. campaign designed to garner Nevadans' support for the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository. The company hired local newscasters to make positive statements. "Once this plan was leaked to the press, it just become a laughing stock," Rampton says. "Local radio disk jockeys were doing humorous skits." After the P.R. initiative, Rampton says, "public opinion was more opposed to the waste repository than before the campaign began. That's where Charlotte Beers' plan is already headed in the Middle East."

It wouldn't be the first time a U.S. propaganda campaign backfired in the region. "Iran prior to the fall of the Shah was barraged with more Western images and promotion than any other country in the region," says Christopher Simpson, a communications professor at American University and author of "Science of Coercion: Communication Research and Psychological Warfare 1945-1960." As a result, he says, "the claims to freedom and democracy made by this propaganda became associated with the corruption and authoritarian methods of the Shah of Iran, so when the Shah went down, the response was very, very reactionary and repressive. Most propaganda of this sort ends up discrediting democracy rather than promoting it."

That's because selling a product simply isn't the same as arguing a belief, whatever branding gurus may say. "Advertising and propaganda is well known to have an impact on short-term decisions -- are they going to buy Tide detergent or Cheer, vote Gore or Bush," says Simpson. "It's also well known to have very little impact on more fundamental beliefs."

Yet if all this is well known, why are Beers and her colleagues -- all savvy, educated people -- pursuing such a course? The reason seems to lie in a fundamental misconception on the government's part -- that people around the world resent America because they don't properly understand it. Like the president, Beers seems convinced that to know America is to love it.

"The central illusion here is that the U.S. is somehow not getting its message across," says Simpson. "The reality is that the U.S. is getting its message across, it's just that the U.S. government doesn't like what people are hearing. The large majority of people in the Middle East understand pretty well what the United States is actually saying and doing, and no amount of propaganda is really going to change that."

After all, as Wahbi points out, people throughout the Arab world already listen to American music and watch American films. "Arabs know a lot about American culture, and anyone in the Arab world would love to come to the United States," he says.

Beers hinted at the real source of Arab anger during her presentation, but she quickly glossed it over. "It's the policy, stupid, they say. Well, it is and it isn't." She went on to explain that when 32,000 adults in eight Arab countries were asked to rank the things most important to them, foreign policy wasn't at the top, "despite what some journalists say."

The problem, of course, is that Muslims don't dispute the fact that America is a fine place to live -- their problem lies in what America is doing to their countries. And while foreign policy may not be among the top concerns of ordinary people, it's clearly among their top problems with the United States.

"Substantive polling shows beyond a doubt that people in the Middle East have no qualms with American culture or democracy," says AbuKhalil. "Their big contention is with U.S. foreign policy, particularly on the Arab-Israeli question."

He continues, "Even if they send dancing monkeys, even if they send Britney Spears to live for five years in the Middle East, it's not going to change how people feel. As long as people are bothered by bombs over the heads of Iraqis and Palestinians, nothing that Charlotte Beers does will change the public mood of the region."

Shares