If you've ever served on a jury, you know the drill. When the parties are done presenting their evidence, the judge instructs you on your job as a juror. "It is your duty to find the facts from all the evidence in the case," the judge will say. "To those facts, you will apply the law as I give it to you. You must follow the law as I give it to you whether you agree with it or not."

Marney Craig listened to words like those in a federal courtroom in San Francisco last week, then walked into the jury room to begin considering the fate of a defendant named Ed Rosenthal. A few hours later, Craig and her follow jurors voted to convict Rosenthal on three federal drug charges. And about five minutes after that, Craig discovered that she had made a horrible mistake: She hadn't been given all the facts about Rosenthal, and she didn't have to convict him.

Rosenthal, it turns out, wasn't the garden-variety marijuana grower that federal prosecutors had made him out to be. In 1996, California voters adopted Proposition 215, which allows seriously ill individuals in need of pain relief to possess and use marijuana with the approval of a medical doctor. Shortly after the passage of Proposition 215, several groups formed "medical cannabis dispensaries" to serve as a source of marijuana for those qualified to receive it. Rosenthal grew his marijuana for one of these dispensaries; in fact, the City of Oakland deputized Rosenthal as an official supplier for one of them.

None of this mattered to the Justice Department prosecutors who indicted Rosenthal. Although candidate George W. Bush proclaimed that states should be free to make their own decisions about the legality of medical marijuana, his Justice Department since the election has taken exactly the opposite approach, aggressively pursuing civil and criminal actions against individuals and groups associated with the medical marijuana movement. Californians and voters in seven other states have legalized medical marijuana, but Washington apparently knows better. "There is no such thing as medical marijuana," a spokesperson for the DEA told the Associated Press last week.

The fact that Rosenthal was growing marijuana for medical purposes would have mattered to Craig and several of the other jurors who convicted him, but they weren't allowed to hear a word of it. In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court held that federal drug laws trumped Proposition 215, and that claims of "medical necessity" provided no defense against federal drug charges. Bound by that ruling, U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer prevented Rosenthal's attorneys from presenting any evidence that Rosenthal had grown marijuana for medical purposes -- let alone that he had done so with the express approval of the City of Oakland.

Craig and her fellow jurors learned the truth about Rosenthal minutes after they returned with their verdict. "A woman came up to us and told us who Ed was and what he did," Craig told Salon in an interview Thursday. "We were sick, absolutely sick."

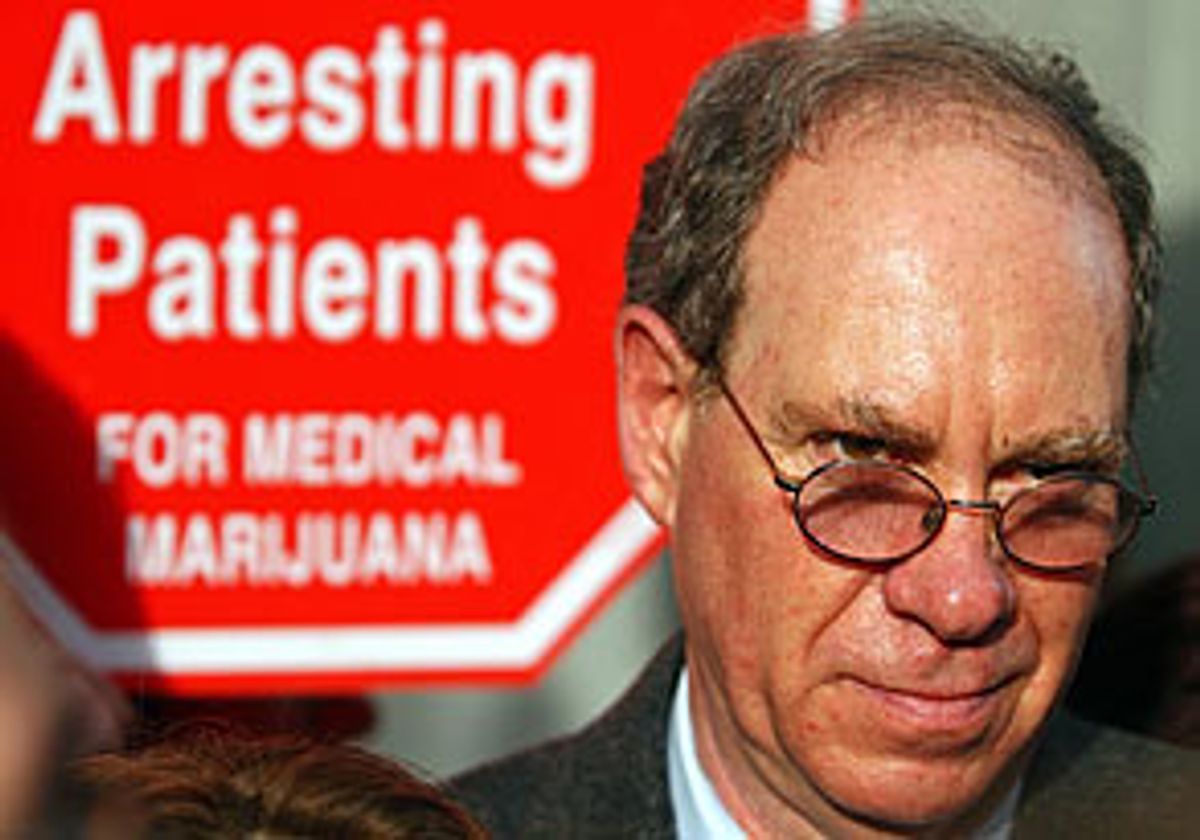

Although Craig, a 58-year-old property manager from Marin County, says she has never spoken in public nor taken a public position on any political issue, she and three of her fellow jurors felt compelled to do something about what had happened. Earlier this week, they held a press conference outside the U.S. District Court in San Francisco where they publicly apologized to Rosenthal and expressed their dismay with a legal system that deprived them of the truth they believe they needed before determining Rosenthal's fate. At their press conference, the jurors were flanked by a number of local government officials -- including San Francisco's district attorney -- all of whom expressed their support for Rosenthal and his work.

In making their case public, the Rosenthal jurors have drawn national attention to two issues: the Bush administration's offensive against state-level decisions on medical marijuana, and the right of a jury to know -- and to act on -- all the facts of a case.

Throughout the history of the United States, juries have sometimes ignored the law in favor of what they considered justice. But jury nullification is a double-edged sword. It's easy to trumpet the bravery of the American jurors who refused to let British authorities jail publisher John Peter Zenger in 1735 for criticizing the odious colonial government of New York, and it's hard to argue with the many Northern jurors who refused to convict runaway slaves. But what of the Southern juries who wouldn't convict a white man charged with a crime against a black man, or the Simi Valley jury that acquitted the cops who beat Rodney King, or the jury that has allowed O.J. Simpson to spend his days playing golf rather than doing time?

Judge Breyer, a Clinton appointee and the younger brother of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, didn't take that risk. He kept the jurors from hearing anything that might lead them to nullify, and he told them they had no right to do so. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, when Rosenthal's lawyer urged the jurors to use their "common-sense justice," Breyer cut him off and said: "You cannot substitute your sense of justice, whatever that is, for your duty to follow the law."

Now that she is outside of Breyer's courtroom, Craig feels another duty: to "right the wrong" that has been done to Ed Rosenthal. It's not at all clear that she will succeed. Rosenthal's conviction carries a mandatory five-year minimum prison sentence, and there may be no way for Judge Breyer to sentence him to anything less. And while Rosenthal plans to appeal, the Supreme Court's 2001 decision leaves little room for even a sympathetic court to rule in his favor. For now, all Craig can do is spread the word about what happened to her -- and what happened to Ed Rosenthal.

Craig talked with Salon by telephone from her home in Novato, Calif.

When you walked into the jury room to begin deliberations, what did you know about Ed Rosenthal and why he had been growing marijuana?

Actually, I don't think we knew anything. During the jury-selection process, we were asked if we had strong views on medical marijuana or on Proposition 215. We were told it was OK to have strong views so long as we thought we could be fair and impartial. That was kind of a tip-off. But the judge continually admonished and instructed us that this was a federal court, that we were bound by the federal law, that we could only consider evidence that was presented in the courtroom, and -- over and over again -- that the reason for growing the marijuana was irrelevant. So, you know, we just bought into the whole thing: "We can't consider that he was growing medical marijuana, and we can't consider that we live in California and voted for Prop. 215 and support medical marijuana." That was not relevant.

So the jurors had some sense that the case was about medical marijuana?

We didn't know that's what it was really about, but we knew that it was an issue.

If you, as jurors, had some sense the case was about medical marijuana, why didn't you just vote to acquit?

Unfortunately, none of us knew who Ed Rosenthal was or what he was doing. The key piece of information that we did not know and that was never mentioned anywhere was that he was employed by the City of Oakland and deputized by the City of Oakland to grow medical marijuana. He was operating under the auspices of the law as an associate of the city. That alone probably would have brought in a different verdict. But that, along with all the other information related to medical marijuana, was never entered into evidence. We were told we couldn't consider any of that.

Did you think that you were permitted to acquit under these circumstances?

We didn't know what we could do under the law because the judge's instructions were very narrow. He said we had to judge this case by federal law only, that federal law takes precedence over California law, that this is a federal courtroom, and that we could only consider evidence that was presented in the trial. We felt we were strictly bound by those guidelines. The judge could have given us other instructions and informed us of our right of juror nullification, but he didn't. We didn't know that we had a right to do anything else other than follow his instructions and follow the letter of the law and convict this man who was presented to us as a major grower. For example, we didn't know that all of his marijuana was for medical purposes. There was no way for us to know that. And even if we might have suspected that, we were so intimidated by the process and by the hostility -- the outright hostility -- of the judge toward the defense. We watched him be so hostile to them, and the prosecutor being so hostile, and here we are 12 people sitting there thinking -- I don't know how many of them thought it, but I did -- "Wow, what's the judge going to do to me if I do something I'm not supposed to do?"

Did any of that hostility suggest to you, "Boy, this defendant must be a really bad guy?"

I knew that they were trying to portray him as a really bad guy. But if you look at him, you can see that he is not. He's the same age I am, and he seems like a really nice guy, and I thought, "What's going on here?" You know, it's so amazing to me that we could have done this. We're all sitting in the deliberation room, and not a single one of us ever felt free to even broach the subject of, "Guys, what are we doing here? Why are we doing this? Does everybody feel OK with this?" And we were all having our doubts, and we were just like sheep. It still amazes me that we did that.

Who is to blame here? You've obviously got a lot of hostility toward the judge, but Congress adopted this law, and the Justice Department chose to prosecute this case.

I'm angry at the system. I'm angry at all of them. The judge was obviously operating within his legal parameters, but he chose the strictest interpretation, and he chose to be fairly dictatorial, and he chose to make it as difficult as possible for the defense to present their evidence and their witnesses. That was obviously his choice, so he has taken an obvious stand. The prosecuting attorney was equally responsible. The feds obviously went after Rosenthal. They were out to get him because of who he was. And that occurred to me in deliberations. I thought, "Why Ed Rosenthal? Why this guy? There's got to be something else going on here."

But didn't that cut both ways in your mind? The Justice Department's interest in Rosenthal might make you think that it had some ulterior motive in going after him, or it might just make you think that the Justice Department considered Rosenthal a serious criminal.

Yeah, but the one thing the defense managed to get out is that he had written two books. [Both were how-to books on marijuana.] Alarms went off in my head when I heard that. I thought, "Wait a minute, this guy has written books? OK, who is he?" I'm sitting there in the trial thinking, "Who is this guy?" And there was no way for us to find out. We weren't reading newspapers or watching TV or listening to the radio because the judge told us not to.

When did you first figure out the truth about Rosenthal?

About five minutes after we walked out of the courtroom. I was devastated. I just could not believe it. Three of us carpooled back up north together, and we could hardly talk. And then I got home and told my husband and my brother and another friend who was around, and their reaction just astounded me. My husband was so upset he left the house and didn't come back for hours. He couldn't even talk to me. He now understands what happened. But I was so upset. I was sitting here thinking, "How did I ever get involved in something like this? How could I, me, who I am, have done what I did to Ed Rosenthal and to his family and to all of the medical marijuana patients?" I was sick.

So you feel some personal responsibility for this?

I do.

But at the same time, you feel that you were constrained from doing anything about it.

We were. We were constrained. And honestly, I was fearful about taking a stand and trying to stick with it unless I could get some support from some of the other jurors, and those of us who made attempts didn't get a lot of support because it was obvious we were committed to following the law. I didn't know what would happen to me if I didn't.

What did you think might happen to you?

You know, I had no idea. I didn't know if I would be prosecuted myself somehow. We're so ignorant of the law, and so ignorant of normal courtroom procedure, and so ignorant of jurors' rights in particular, that we had no idea. I didn't know I could sit there and say, "I can't do this. I'm not going to convict this man."

Have you spoken with Rosenthal since you handed down your verdict?

We actually ran into him in the elevator on the way up to the [bail] hearing. The door opened, and we stepped in and there he was with his family. I hugged him and I told him I was sorry. I was crying. He was with his wife and daughter, and the three of them couldn't have been nicer to us. I was standing there in tears, and they said, "Don't apologize. It wasn't your fault. We know what happened."

And did you speak directly with Rosenthal?

I did have an opportunity to speak with him, yeah. He's taking such a positive attitude toward this. He said, "Whether or not I go to prison, this has become a much larger issue because of what you're doing, and we will be able to accomplish much more because of the outcome of the trial and the fact that all of you have come forward." And that's how he is looking at it. He's not looking at his years in prison. He's looking at what we can do now with the platform that we have.

And what did you tell him?

I told him that he's an amazing man, that I'm sorry I didn't know who he was before, and that I'm committed to trying to help him get a new trial. I don't know if I have any clout in that at all. Obviously, I have no legal standing at all. But he knows that I'm willing to do any public speaking or talk to as many people as I can to try to get the word out and to make people understand. There are major issues here. We're dealing with medical marijuana here, we're dealing with states' rights, we're dealing with jurors' rights, and we're dealing with Ed Rosenthal needing a fair trial. The whole system is so flawed.

Shares