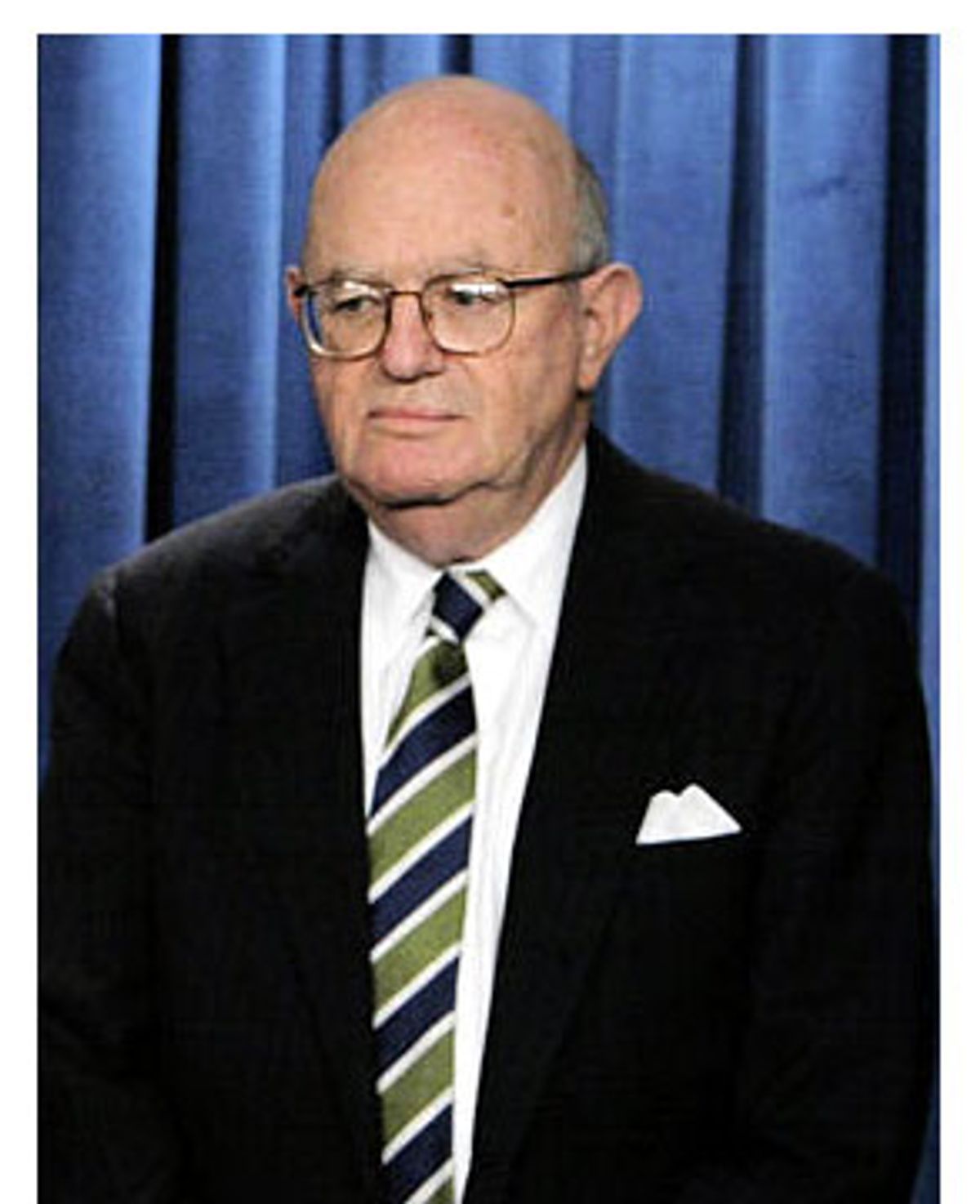

Judge Laurence Silberman, George Bush's nominee to co-chair the commission investigating U.S. intelligence on Iraq, knows quite a bit about the murky intersection between facts and ideology. The senior judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington has been near the febrile center of the largest political scandals of the past two decades, from the rumored "October surprise" of 1980 and the Iran-contra trials to the character assassination of Anita Hill and the impeachment of President Clinton. Whenever right-wing conspiracies swing into action, Silberman is there.

A veteran of the Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan administrations who is close to Vice President Dick Cheney, Silberman has a reputation as a fierce ideologue who doesn't let his judicial responsibilities get in the way of his Republican activism. David Brock, the repentant former right-wing journalist and Silberman protégé, describes his former mentor as "an extreme partisan" who seems to relish "the political wars." Kevin Phillips, the former Nixon staffer who authored the recent "The Bush Dynasty," said on NPR on Monday, "In the past, Silberman has been more involved with coverups in the Middle East than with any attempts to unravel them." Ralph Neas, president of the liberal advocacy group People for the American Way, calls him "the most partisan and most political federal judge in the country" and says his appointment is "stunning and disgraceful."

Silberman's panel, which is supposed to investigate U.S. intelligence on Iraq, Iran, North Korea, Libya and Afghanistan, won't report its findings until March 2005, long after the presidential election. Silberman will be balanced on it by other more moderate or more independent figures, including co-chair Charles Robb, a former Democratic senator and Virginia governor; Republican Sen. John McCain; and Judge Patricia Wald, Silberman's colleague on D.C. Circuit Court, a woman he is said to hate.

Yet Silberman's place at the head of the commission has already raised doubts about its credibility, given that Silberman has often behaved as if his paramount role as a federal judge is to protect Republicans, persecute Democrats and slander anyone who disagrees.

"My guess is that he's on there for protection," says Neas. "To protect the president at all costs and to do what he's done in the past with respect to protecting Republican presidents from scrutiny. I think he envisions himself as a mastermind behind many right-wing initiatives, whether it's helping guide Clarence Thomas through the confirmation hearings or helping guide David Brock through all the anti-Clinton initiatives."

Besides his commitment to Republican power, Silberman is known for his temper. Several years ago, he told colleague Abner Mikva, "If you were 10 years younger, I'd be tempted to punch you in the nose."

"He's very volatile," says Brock, whose 2002 book, "Blinded by the Right," was a mea culpa for his career as a conservative operative. "He has certainly made derisive comments about many journalists and about his colleagues on the bench. Those comments were intemperate."

Of course, given his own admitted transgressions, Brock himself might not be considered a reliable source. Still, as a report on Silberman from the Alliance for Justice, a liberal group working "to promote a fair and independent judiciary," points out, Silberman has never sought to disprove or deny any of Brock's charges that he worked behind the scenes to bring down Republican foes like Hill and Clinton. Similarly, the report says, "None of Silberman's friends and allies -- those in a position to refute Brock's charges and with an interest in doing so -- have yet challenged a single claim he made."

Silberman's sojourn in the world of political scandal began during the run-up to the 1980 presidential election when, as a member of Ronald Reagan's campaign staff, he, along with Robert C. McFarlane, a former staff member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and Richard V. Allen, Reagan's chief foreign policy representative, met with a man claiming to be an Iranian government emissary. The Iranian offered to delay the release of the 52 American hostages being held in Tehran until after the election -- thus contributing to Carter's defeat -- in exchange for arms.

A controversy continues to rage over whether the Reagan team made a bargain with the Iranians, as alleged by Gary Sick, a former National Security Council aide in the Ford, Carter and Reagan administrations who now teaches at Columbia University. Yet no one denies that the meeting Silberman was at took place, and although Silberman has said the Iranian's offer was immediately rejected, none of the three Reagan operatives ever told the Carter administration what had happened. McFarlane, Allen and Silberman have all since insisted that they don't know the name of the Iranian man they met with.

After working for Reagan's election, Silberman was rewarded with an appointment to the D.C. Court of Appeals, the second most powerful court in the country. After the Iran-contra scandal, he was part of a three-judge panel that voted 2-to-1 to reverse Oliver North's felony conviction. Voting with him was David Sentelle, a protégé of Jesse Helms who according to Brock named his daughter "Reagan" after the president who put him on the bench.

In his book "Firewall: The Iran-Contra Conspiracy and Cover-Up," Iran-contra special prosecutor Lawrence Walsh, a Republican who served as deputy attorney general during the Dwight Eisenhower administration, described Silberman as "aggressively hostile" during oral arguments. Walsh wrote that he regretted not moving to disqualify him.

The year after he ruled North innocent, Silberman joined in the right-wing campaign to defame Anita Hill, who had accused Clarence Thomas, George H.W. Bush's nominee to the Supreme Court, of sexual harassment. It was during the attack on Hill that the Silbermans took Brock under their wing.

Brock met Silberman through his wife, Ricky Silberman, who had worked under Thomas at the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission and served as a source for a story Brock wrote about Thomas' confirmation hearings.

In 1992, after Thomas had been confirmed, Brock began researching "The Real Anita Hill," a savage assault on Hill's character that Brock later apologized for. Laurence Silberman was a source for the book, feeding Brock gossip. "Judge Silberman speculated that Hill was a lesbian, 'acting out,'" Brock wrote in "Blinded by the Right." "Besides, Silberman confided, Thomas would never have asked Hill for a date: Did I know she had bad breath?"

Brock's Anita Hill book portrayed Judge Patricia Wald, Silberman's colleague on the D.C. Circuit Court, as a "conspirator in the campaign against Thomas," as he wrote in "Blinded by the Right." "Of course it was none other than Judge Silberman who gave me the false information on his colleague Pat Wald, whom he hated with a passion," Brock wrote.

Silberman was more than just a source to Brock: He was also Brock's guide and advisor. Brock says Silberman would read drafts of the Anita Hill book and comment on them, and writes that he thought of the Silbermans as "surrogate parents."

And it was the Silbermans who encouraged him as he became one of the chief propagandists of the right's anti-Clinton jihad. In 1993, Brock wrote "Troopergate" for the American Spectator. A lascivious would-be exposé about Clinton's sex life, its mention of a woman named "Paula" spurred Paula Jones to introduce herself to the world at the Conservative Political Action Conference, where she held a press conference to claim that Clinton had sexually harassed her. It was that story that ultimately led to the impeachment of Clinton.

Brock had been ambivalent about publishing the article at all. He didn't doubt the truth of the troopers' stories -- that came later -- but he says, "My doubts had to do with taking what seemed to be an unprecedented step in violating the personal privacy of the president." He asked several people for advice and got mixed responses, but Silberman was extremely encouraging.

"He wrapped his advice in an appeal to my ego," Brock writes. "The trooper story would be much bigger than the Anita Hill book, he predicted. Clinton would be 'devastated,' and therefore the story could only greatly enhance my reputation. Sitting in his favorite tan chair, Scotch in hand, the judge told me he felt sure that if the same story had been written about Ronald Reagan, it would have toppled him from office. Clinton, he surmised, might be toppled as well. Of course, the liberal media might ignore the story to protect Clinton, but in conservative circles, I would be king. When I heard that, I was over the fence. I left the Silbermans' house with a racing pulse."

"When I look back on it, I think it's possible that maybe if he had thought otherwise, the article never would have been published," Brock says.

Both Silberman and his wife continued to play important behind-the-scenes roles in the Clinton investigations, something that didn't stop the judge from ruling on important aspects of the case. As Brock reports, Ricky Silberman founded an anti-feminist group, the Independent Women's Forum, which received backing from Clinton-hating sugar daddy Richard Mellon Scaife (Lynne Cheney, wife of Dick, was a member of its board) and which filed a friend of the court brief in the Paula Jones sexual harassment lawsuit against Clinton. Ricky Silberman approached Ken Starr to handle the brief. It was his introduction to the case. He turned it down, but he later consulted with Jones' lawyers in telephone conferences.

Later, a panel of judges headed by David Sentelle appointed Starr to investigate Whitewater -- which morphed into the Lewinsky investigation.

During that investigation, the Clinton administration claimed executive privilege to prevent the Secret Service from testifying about Clinton's relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Silberman sat on the Federal Appellate Panel that heard the case.

As Jonathan Broder reported in Salon at the time, "U.S. Judge Laurence H. Silberman wrote a scathing opinion that accused [Attorney General Janet] Reno of acting not on behalf of the U.S. government, but in the personal interests of President Clinton. Then, using language seldom seen in the federal judiciary, Silberman questioned whether Clinton himself, by allowing his aides to attack Starr, was 'declaring war on the United States.'"

Of course, if Brock's allegations against Silberman are true -- and, as the Alliance for Justice points out, neither Silberman nor his allies have ever refuted or even challenged them -- then Silberman shouldn't have been ruling on the case at all.

Indeed, that's why the Alliance for Justice was planning its report on Silberman even before Bush chose him to head the intelligence panel. The investigation was intended as a case study in the danger of elevating the kind of far-right judicial nominees Bush has put forward.

"The Judicial Selection Project of the Alliance for Justice has prepared this report on the record of Judge Silberman before and after taking the bench," it begins. "Why? Because federal judges should not do what Brock claims Silberman did. They are supposed to be impartial arbiters, not partisan advocates. Because a judge like Silberman enjoys an enormous amount of influence in this country, and not just by virtue of his seat on the second most prestigious and powerful court in this country; he is known as a 'feeder judge,' having sent some twenty of his clerks to the Supreme Court and, according to former clerk Paul Clement, a 'tremendous number' of Silberman's former clerks are currently working in the Bush administration. Because even those cynics who believe that federal judges are guided on the bench by partisan ideology should be dismayed by Silberman's alleged conduct off the bench."

For Silberman's critics, naming him to get to the bottom of one of the most divisive political controversies of our time is even more egregious than Bush's attempt to put Henry Kissinger in charge of the 9/11 investigation.

"Even the word 'chutzpah' does not describe this appointment of Silberman," Phillips said. "This is not bravado, but arrogance."

Shares