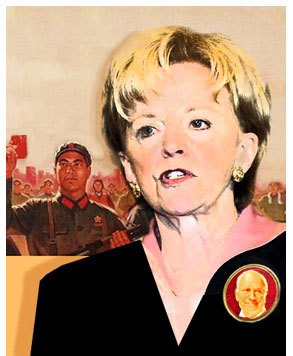

Stumping for the Bush-Cheney reelection campaign, vice presidential spouse Lynne Cheney, ferocious culture warrior of the conservative movement, has been trying to soften her image. The controversial former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities in the Reagan and first Bush administrations no longer mentions her signature issues: the evils of feminism, or how liberal academics are teaching students to hate America. Mostly she talks about her grandchildren, beaming with pride that one of them calls her “Grandma of the United States.”

Such a sweet old lady would never presume to meddle where she has no authority, would she? After all, Cheney has long shuddered at the horror of Hillary Clinton. “Mrs. Clinton got herself in a certain amount of trouble by operating from a platform where she really didn’t have a mandate from the voters to establish policy,” Cheney sniped to the Daily Telegraph of London in 2001. And in a Hillary-bashing forum at the conservative American Enterprise Institute in 2000, Cheney remarked about the then-first lady: “The hypocrisy is the thing that is most distressing.”

But now, unelected and unappointed, Lynne Cheney is back in charge at the National Endowment for the Humanities, operating without that pesky “mandate from the voters” through handpicked surrogates in key positions. “It’s pretty obvious that she’s running the agency,” William Ferris, a history professor who headed the NEH from 1997 to 2001, said of Cheney.

The endowment’s chairman, Bruce Cole, a Renaissance art scholar from Indiana University, is a conservative ally of Cheney whom George H.W. Bush had appointed to the National Council on the Humanities, the advisory body that oversees grant-making for scholarly research, preservation, media and teaching projects at the $137 million agency. At Cole’s swearing-in as chairman in December 2001, Cheney and her husband, Vice President Dick Cheney, showed up to clink glasses. The unusual high-level attention sent a message that was not lost on the endowment’s staffers.

Moreover, two close Cheney friends have been installed in key positions at the agency. In charge of day-to-day operations is deputy director Lynne Munson, who was Cheney’s special assistant at the NEH from 1990 through 1992 and later followed Cheney to her fellowship at the American Enterprise Institute. And Celeste Colgan, a member of the National Council on the Humanities, is a former Halliburton official and longtime Cheney family crony who was Cheney’s deputy at the NEH from 1986 through 1992. Both women, according to many sources close to the endowment, are widely perceived to be responsible for an Orwellian atmosphere of secrecy and paranoia that has descended over the agency, a Cheney family hallmark.

Though she has no formal standing in day-to-day management, Cheney’s photograph is featured prominently on the agency’s Web site, and she always seems to pop up at chairman Cole’s side for important announcements. In 2002, when President Bush unveiled a special $10 million White House-backed education program on American history, “We the People,” the first audience member he thanked in the Rose Garden ceremony was Lynne Cheney. The president did eventually acknowledge Bruce Cole as well, though he got his name wrong, calling him “Bob.”

During her chairmanship of the agency from 1986 through 1992, Cheney was known for killing research projects deemed offensive to conservative orthodoxy, scribbling “not for me!” on proposals dealing with race, gender discrimination or the legacy of slavery. She considered the endowment so irredeemably left-wing that she campaigned to abolish it. But times have changed. Republicans control the White House and Congress. Democrats are cut out of the process. Now conservatives view the agency as a useful tool for propagating the kind of uplifting and generally uncritical version of American history they believe necessary for national greatness, as Cheney explained in a CNN interview last year: “American history that’s taught in as positive and upbeat a way as our national story deserves.”

A spokeswoman for Cheney, Maria Miller, said the vice president’s wife was unavailable to comment for this article. An NEH spokesman, Erik Lokkesmoe, said Cole and Munson were traveling and similarly unavailable for comment, and that he could not pass Salon’s request for comment on to Colgan, whose home phone number in Denver is unlisted, because no one at the NEH knew how to reach her. (How do they summon Colgan to Washington for quarterly meetings of the National Council? Smoke signals?)

Once left for dead, its budget slashed nearly 40 percent during the Newt Gingrich “Republican revolution” of the mid-1990s, the NEH has seen its funding nudged upward during the Bush administration to $137 million. That’s still considerably less than the $177.5 million the agency received in 1994, pre-Gingrich. The problem now is not what projects are being funded, because many worthy scholarly or educational pursuits are receiving support, though only if they meet conservative approval. The issue, rather, is what’s not being funded, which viewpoints are being excluded, and what critical-thinking tools for students are being suppressed at a time when it is more important than ever to understand (and thus counteract) the dangerous global rise in hostility toward America.

Instead, at an agency meant to foster intellectual exploration and knowledge, NEH staffers’ phone lines are being monitored to catch — and punish — anyone who dares take a call from a reporter, according to Angela Iovino, a former program officer at the agency who keeps in touch with her anxious former colleagues. In an apparently punitive move, the NEH inspector general opened an investigation of a former assistant chairman of the agency, a professor of French and Italian at Indiana University named Julia Bondanella, after she was quoted in a Chronicle of Higher Education article that exposed the return of Cheney-era “flagging” of proposals for rejection that don’t adhere to conservative orthodoxy. Meanwhile, President Clinton’s appointees to the National Council on the Humanities, the oversight board that plays a critical role in approving grants, have been marginalized to the point where one — Ira Berlin of the University of Maryland, a prominent historian of slavery — quit in anger.

The absurdity is that it is now easier for reporters to ring up officials at the Central Intelligence Agency to chat about Osama bin Laden than ask a staffer at the endowment why a project on, say, ethnic Chinese in Cuba didn’t get funded. Many scholars, apparently fearful of jeopardizing chances for future funding, responded either with silence or with a nervous, clammy stuttering when I asked to interview them. “People are scared and intimidated,” explained Ferris. “What’s happening there now is completely contrary to the values the endowment is meant to promote.”

Cheney, who holds a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin, is a prolific author of polemical tracts, children’s history books and fiction, including a 1981 novel “Sisters,” about a 19th century feminist. (Perhaps because of the novel’s sympathetic treatment of lesbianism, Cheney has dropped mention of the inconvenient “Sisters” from her résumé, even though her daughter, Mary, is gay. She has also suppressed the book so that it is no longer in print.) In 1986, Cheney was appointed to head the NEH, replacing conservative moralizer (and furtive gambling addict) William Bennett, who had left to become Ronald Reagan’s secretary of education. Hailed by conservatives for her back-to-basics approach to the humanities at a time when the academy was seized by postmodernism, deconstructionism and other intellectual trends, her tenure was turbulent. Research proposals dealing with race, ethnicity or gender — scorned by Cheney as too negative or subversive to the Western canon — were often summarily rejected, despite receiving high marks from peer review panels. Even Cheney’s friends or fellow Republicans found that if political points could be scored, she wouldn’t hesitate to twist their views into cartoon-like caricatures that played well with Rush Limbaugh and the right-wing press.

A raging controversy in the 1990s over proposed national teaching standards for history, for example, showed how “the Grandma of the United States” had no problem eating her own, if it meant helping her husband get to the White House. As NEH chairwoman, Cheney had selected a teaching center at the University of California-Los Angeles to develop the history standards for elementary and high schools; the choice was in large part because of her friendship with a professor there named Charlotte Crabtree. Bruce Robinson, who as a program officer for education at the NEH was nominally assigned to oversee the grant, said the project was actually administered out of Cheney’s office. “And they gave that center renewals of grants without peer review, year in and year out,” Robinson said.

Cheney kept folders about the history standards on her desk, Robinson said, while Crabtree, the UCLA professor in charge of developing the standards, lavished praise on Cheney in her grant proposals. “Lynne Cheney and Charlotte Crabtree were, for a few years, great buddies,” Robinson told me. “Then the standards came out.”

The year was 1995, and after overseeing the successful Persian Gulf War as secretary of defense, Dick Cheney was contemplating running for president. Suddenly, his wife turned on the history teaching standards she had nurtured, attacking them in television appearances, political forums and in opinion pieces as whacked-out, far-left anti-American propaganda. In this manner, Lynne helped whip up the right-wing base that Dick Cheney would need to mount a bid for the White House into a politically useful frenzy.

“She just bludgeoned the standards,” Robinson said. “She said they emphasized things like the mafia and slavery. And she turned on Charlotte Crabtree. Lynne Cheney was basically writing checks for that thing. Then she just stuck a knife in it and turned it. It drives me crazy the storm she raised over the history standards. I still hear people repeat what she accused the standards of doing, which were not true. What a waste of money that was. What a step backwards. God, that makes me angry.”

Gary Nash, a colleague of Crabtree’s at UCLA who worked with her on the teaching standards, confirmed Robinson’s account. “She was really crushed by the way Lynne Cheney turned on the standards, because she had been very friendly with her, almost like a sorority sister,” Nash said. “Afterwards, she stepped down as national director of the schools center [at UCLA] and withdrew from all the commissions and councils she had sat on in Washington and California. It was really devastating for her.”

Crabtree did not return a phone call seeking comment. But she co-authored, with Nash and Ross Dunn, a book on the experience, “History on Trial: Culture Wars and the Teaching of the Past.” It was one of several anguished accounts published by prominent academics who found themselves bloodied by Cheney.

Another book, “Leaving Town Alive,” by Republican John Frohnmayer, described how a howling pack of conservatives led by Cheney ousted him as head of the NEH’s sister organization, the National Endowment for the Arts, in 1992. Frohnmayer had the misfortune of taking over the NEA after his predecessor had funded the work of controversial artists Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano. Over at the NEH, meantime, Cheney was winning plaudits — and budget increases from Congress — for her funding of Ken Burns’ popular documentary series on the Civil War. “I once proposed to her that we work together. The look of horror on her face was so absolute. They weren’t going to touch us with a 10-foot pool. We were the bad children,” Frohnmayer, now retired from law practice in Montana, told me.

Although the work of the avant-garde Mapplethorpe and Serrano, whose photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine sparked a conservative furor, weren’t much to Frohnmayer’s liking, he said he felt an obligation to the First Amendment not to interfere with the judgment of peer review panels and the National Council for the Humanities in supporting the art. “I used to wonder whether the First Amendment applied to what the hell we were doing there. The First Amendment always protects the speaker. But Lynne Cheney was much more interested in the conservative audience out there. And that does great damage to the First Amendment,” Frohnmayer said.

Already floundering, Frohnmayer sealed his fate by declining to block other controversial grants selected by peer reviewers and the National Council. “I felt that the process was important to protect. That’s maybe the main difference between Lynne Cheney and me. She didn’t care what the process was; she was willing to circumvent it. I felt if the panel and National Council recommended it, that I as chair was not going to veto it unless I had a very good reason.”

With Cheney and other conservatives creating a frenzy and with a tight presidential contest with Bill Clinton looming, George H.W. Bush fired Frohnmayer. The former NEA chairman, who holds a master’s degree in Christian ethics, laughs about the experience in retrospect. But he said he remains proud of the principles he stood up for. “We are a wildly diverse country, and we have a lot of different viewpoints being represented by a lot of different applicants,” he said. “For me as chair to simply impose my own personal tastes was to me not an appropriate use of the chairman’s veto power.”

Cheney certainly felt otherwise. Angela Iovino, who worked at the NEH during Cheney’s chairmanship, recalled a brouhaha about the Aztecs that sent Cheney’s culture-war beanie cap spinning off her head. The problem was that Cheney discovered that the ancient natives of Mexico had practiced human sacrifice. “She went nuts on that. She threw her hands in the air and said, ‘How can we look into the cultures of these savages?'” Iovino said. “We just looked at each other. What do you say to something like that? We just stared, mutely. She didn’t really foster conversation.”

The scene was indicative of Cheney’s basic ignorance of the world outside American borders, said Iovino, a language expert. “Lynne Cheney is a hardworking woman, but it was hard to talk to her about anything outside the Republican conservative agenda. She rarely knew what language was spoken in what country. She thought Hebrew was spoken in Jordan,” Iovino said.

Throughout such controversies, Cheney’s loyal lieutenants — Lynne Munson and Celeste Colgan — were at her side, absorbing the lessons that would guide them a decade later when they returned to the NEH as Cheney’s surrogates.

Of the two, Munson is considered the most punitive, because she controls the day-to-day operations of the endowment. In the hallways, she has been overheard boasting loudly that she has spoken recently with Cheney. Unlike previous holders of the deputy’s position, Munson lacks a Ph.D., an essential qualification whose absence, her detractors say, is evidence that pure politics is behind her assignment.

Colgan, 65, earned a Ph.D. in English literature from the University of Maryland and has known Cheney for decades. From 1986 through 1992, Colgan was Cheney’s deputy at the NEH. Later, she spent two years as director of the Wyoming state commerce department, then followed Dick Cheney to Halliburton, where she became vice president of administration. Colgan is widely viewed as Cheney’s eyes and ears on the National Council.

Robinson, the retired NEH program officer, remembers Colgan as a fearsome presence. One of the good things Cheney had done, Robinson said, was secure three years of funding from the Reader’s Digest and Geraldine R. Dodge foundations for “thinking” sabbaticals for harried high-school teachers. When the money ran out, Robinson, who oversaw the sabbatical program, secured a commitment from the foundation to extend the program another year. Colgan was livid. “She blew her cork at me, and she accused me of feathering my own nest. I had no idea what she was talking about. But Celeste just absolutely dragged me across the carpet, accusing me of trying to take some personal advantage from this. To this day I still don’t know what she was talking about,” Robinson said.

Bill Clinton’s election in 1992 moved Cheney out of the NEH and over to the American Enterprise Institute, where Richard Perle and other neocons were plotting what then seemed the improbable invasion of Iraq. Munson, who had been Cheney’s special assistant at the NEH, followed her to the think tank, where she wrote a book, “Exhibitionism: Art in an Era of Intolerance,” that ridiculed the kind of modern art that John Frohnmayer had defended in the early 1990s on free-speech grounds. Both Cheney and Munson remained active in a conservative anti-feminist group called the Independent Women’s Forum, funded by the Clinton-hating Pittsburgh billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife.

Cheney banged out a new book: “Telling the Truth: Why Our Culture and Our Country Have Stopped Making Sense and What We Can Do About It,” published in 1995. Also that year she founded, with Sen. Joseph Lieberman, D-Conn., the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, an advocacy group to fight “political correctness,” a perch she used to bash Clinton’s nominee to succeed her at the NEH, University of Pennsylvania president Sheldon Hackney. Hackney had sinned in not interfering in the university’s regular adjudication process when a group of black students accused another student of racism for taunting them as loud and rowdy “water buffalo.” The accused, who was born in Israel, said he’d badly translated a Hebrew expression used to describe inconsiderate people. A Cheney appointee to the National Council on the Humanities, University of Pennsylvania professor Alan Kors, led the attack from within the university on Hackney, while Cheney stoked conservative anger through her television appearances. (A student journalist at Penn who was also instrumental in promoting the story, Stephen Glass, went on to notoriety at the New Republic, where he was eventually exposed as a serial fabricator.)

As Hackney later wrote in “The Politics of Presidential Appointment: A Memoir of the Culture War”: “I followed the story in the press of some idiot named Hackney, who was either a left-wing tyrant or a namby-pamby liberal with a noodle for a spine. My critics couldn’t decide which. Not only did I not recognize him, I didn’t much like him either.” In the end, the Senate overwhelmingly confirmed him.

In a parallel universe, meanwhile, Dick Cheney had figured out he would not be president and took his consolation prize as head of oil services conglomerate Halliburton. He invited Colgan to follow. And so his wife’s old friend became Halliburton’s vice president for administration and secretary of the Halliburton corporate foundation. She also served as a liaison to the company’s executive compensation committee, which rewarded Dick Cheney with stock, options and other income worth $36 million in 2000. (Told where the woman who had accused him of feathering his nest had landed, Robinson, after a stunned pause, said: “It’s amazing how cozy these people are.”)

Then, George W. Bush’s disputed election swept the Cheney crowd back in at the NEH. Turmoil quickly followed as Munson began stacking the supposedly independent peer review grant panels and the National Council with conservatives. At the same time, Munson and Cole revived the Cheney-era practice of “flagging” research proposals for rejection that were insufficiently patriotic.

“It was Lynne Munson who had all these harebrained ideas about peer review panels,” said Robinson, who retired from the NEH in 2002. He said Munson began requiring program officers to submit their choices for peer review panels to her for approval, thus eliminating “wrong-thinking” people from the front lines of grant making. Other sources with knowledge of the process confirmed Robinson’s account. NEH spokesman Lokkesmoe declined to comment.

At the same time, Clinton academic appointees to the National Council were removed from their areas of expertise, where they had once had influence over how to distribute NEH grant money. Instead, they were assigned to powerless, non-grant-making panels that oversee the backwater state humanities councils. Among the Clinton-era scholars who were disappeared in this manner were Maryland’s Ira Berlin; University of Virginia history professor Edward L. Ayers; Susan F. Wiltshire, a classics professor at Vanderbilt University; Evelyn Edson, a history professor at Piedmont Virginia Community College; and Pedro Castillo, a history professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Berlin, a prominent historian of Southern and African-American history, made no secret of his anguish, telling numerous colleagues of his anger, humiliation and intention to resign. But either too traumatized or too afraid to speak publicly about the experience, Berlin responded neither to phone messages left at his home and office nor to e-mails. In response to questions from Salon about Berlin’s resignation, NEH spokesman Lokkesmoe released a heavily edited version of the historian’s resignation letter highlighting bland pleasantries. “It pleases me much to have participated in its [NEH’s] great work,” Berlin wrote, according to the excerpt released by NEH.

Bush appointees to the National Council include conservative intellectuals known for tendentious argument. Harvard professor Stephan Thernstrom is co-author, with his wife, Abigail Thernstrom, of “America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible,” a 1999 book that argued that racial progress has been more extensive than liberals portray and would be even further along without affirmative action. Also on the council is Emory University’s Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, who attacks traditional feminism and has been associated with the same Independent Women’s Forum where Cheney and Munson have found homes.

Others are notable for their connections to right-wing academic advocacy groups associated with Cheney. Council member Jeff Wallin, for instance, is listed on tax returns as treasurer of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, a nonprofit group Cheney helped found to lobby against tenure and perceived liberal bias in universities. The NEH identifies Wallin as president of the American Academy of Liberal Education, yet another conservative front group fighting perceived bias in universities; the organization counts Fox-Genovese among its board members.

While the NEH has become a closed circuit of self-reinforcing conservative worldviews, stories are flying about grant proposals that are being turned down or altered to secure NEH funding. According to several sources, a well-rated proposal for a television documentary on Barry Goldwater, considered the father of the modern conservative movement, was rejected because the right wing has since turned on the 1964 Republican presidential nominee. Before his death, Goldwater came out in favor of gay rights and women’s rights, denounced the religious right, and took other positions that are anathema to conservatives. Lokkesmoe had no comment.

By last January, the Chronicle of Higher Education had published a lengthy investigation on why many apparently worthy grants were not receiving funding from the NEH. The Chronicle found that the Cheney-era practice of “flagging” projects was back. William Ferris told me he rarely blocked a proposal that had been recommended by peer reviewers and the National Council. “Maybe once a funding cycle,” he said.

But the Chronicle, citing internal NEH documents, reported that 51 out of 1,448 applications that were submitted to the agency in November 2002 had been flagged, or 3.5 percent of the total. A year later, the percentage of flagged proposals had risen to 4 percent, or 55 out of 1,402 applications submitted in November 2003, the newspaper said. In response, the NEH began an apparent witch hunt.

Gerardo Renique, a history professor at the City College at the City University of New York, said he received a hostile phone call from a member of the NEH’s Office of the Inspector General after he was quoted expressing bewilderment that the NEH had rejected his proposal, “Chinese Diasporic Communities and Nationalism in Peru and Cuba, 1920s-1930s,” despite its high marks from peer reviewers. The Chronicle found that Renique’s proposal had been deep-sixed because the NEH political appointees objected to his spending grant money in Cuba, despite the fact that neither the Treasury nor State Departments cared. But hard-line, Republican-voting Cubans-Americans in the key swing state of Florida care a lot.

Renique, in a phone interview from Mexico, where he was forging ahead on his project with alternative funding, said the NEH inspector general staffer who called him “sounded like a cop. He said, ‘Are you Gerardo Renique?’ I said, ‘Yes, who’s calling?’ And then he started grilling me: ‘Did you give information to the Chronicle? Did you contact them? Did you talk to them?’ It was a very unpleasant conversation, because if he wanted information, he could have used another style. He was very confrontational,” Renique said.

The history professor admitted to the inspector that he’d answered the Chronicle reporter’s questions. But he insisted he had not alerted her to the rejection of his research proposal. The investigator hung up. Soon, the NEH’s allegedly independent auditor of waste, fraud and abuse — Sheldon Bernstein — was on the trail of another person quoted in the Chronicle article, Julia Bondanella, a former assistant director of the NEH who said she left because the agency had become politicized. A professor of French and Italian at Indiana University in Bloomington, Bondanella received a threatening letter accusing her of disclosing confidential information about NEH employees and grant applications. She has been forced to hire a lawyer. Bernstein’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Contacted by Salon, Bondanella declined to comment, citing the ongoing investigation, which is costing her dearly in legal fees. But she told the Chronicle in May that the NEH inspector general was “just trying to dig up dirt” on her. “Clearly, they’re trying to keep me from saying anything,” she said. Yet it could have been worse: The Justice Department quietly rejected feelers from the political appointees at NEH about opening a criminal investigation of Bondanella, according to sources. NEH spokesman Lokkesmoe said he knew nothing about any contact with Justice. I asked him to query the person who would know: Lynne Munson. But he never got back to me.

If there is any silver lining to the Cheney II era at NEH, it is a well-regarded American history education program called “We the People,” designed to raise the abysmal level of knowledge among students, who studies indicate often can’t identify who the United States fought in World War II, what the term “Reconstruction” refers to, or even name the three branches of government.

In a 2002 speech, Cole explained the program’s goals. “Defending our democracy demands more than successful military campaigns. It also requires an understanding of the ideals, ideas and institutions that have shaped our country.” The humanities, he added, “are part of our homeland defense.”

On the surface, it’s hard to quibble with “We the People,” which has funded books for schools, filming of documentaries about historical figures, such as “Little Women” author Louisa May Alcott, and lectures by eminent historians. But there is a tilt to the presentation that many scholars find troubling.

“I strongly support their effort to promote the better teaching of history at the high school level. But the danger is that this ‘We the People’ thing could become a merely celebratory history,” said Eric Foner, a history professor at Columbia University and longtime Cheney critic. “We don’t need to teach history that smashes America. But if you put forward a version of American history that it began perfect and has been getting better ever since, you’re not equipping students to think critically.” Cheney, Foner added, “always saw history in terms of generating a kind of patriotism for the country.”

Robinson, the former NEH program officer, agreed with Foner. An expert on South Asia and Islam, his view that many academics have glossed over negative aspects of Islam, such as a lack of rights for women, would not be out of place in the National Review. But he still sees peril in Cheney’s approach to history. “If I were still there, what would be driving me up the wall was when 9/11 broke out, and Lynne Cheney came out with a statement saying something like, ‘This just shows we need to know more about American history and the founding fathers.’ Well, of course my feeling was, this demonstrated Americans’ need to know a lot more about the rest of the world,” Robinson said.

The NEH Web site features a photograph of Cheney in a bright red jacket before a preserved section of the Berlin Wall near Washington, promoting the “We the People” “Freedom Bookshelf” program that provides schools with books meant to encourage reflection on the nature of freedom. On Cheney’s approved reading list is George Orwell’s frightening portrayal of mind control in a totalitarian society, “1984.” On her unapproved thought list, undoubtedly, is that anyone might see a parallel with Cheney’s bludgeoning of alternative viewpoints. But, as Big Brother said: “Ignorance is Truth.”