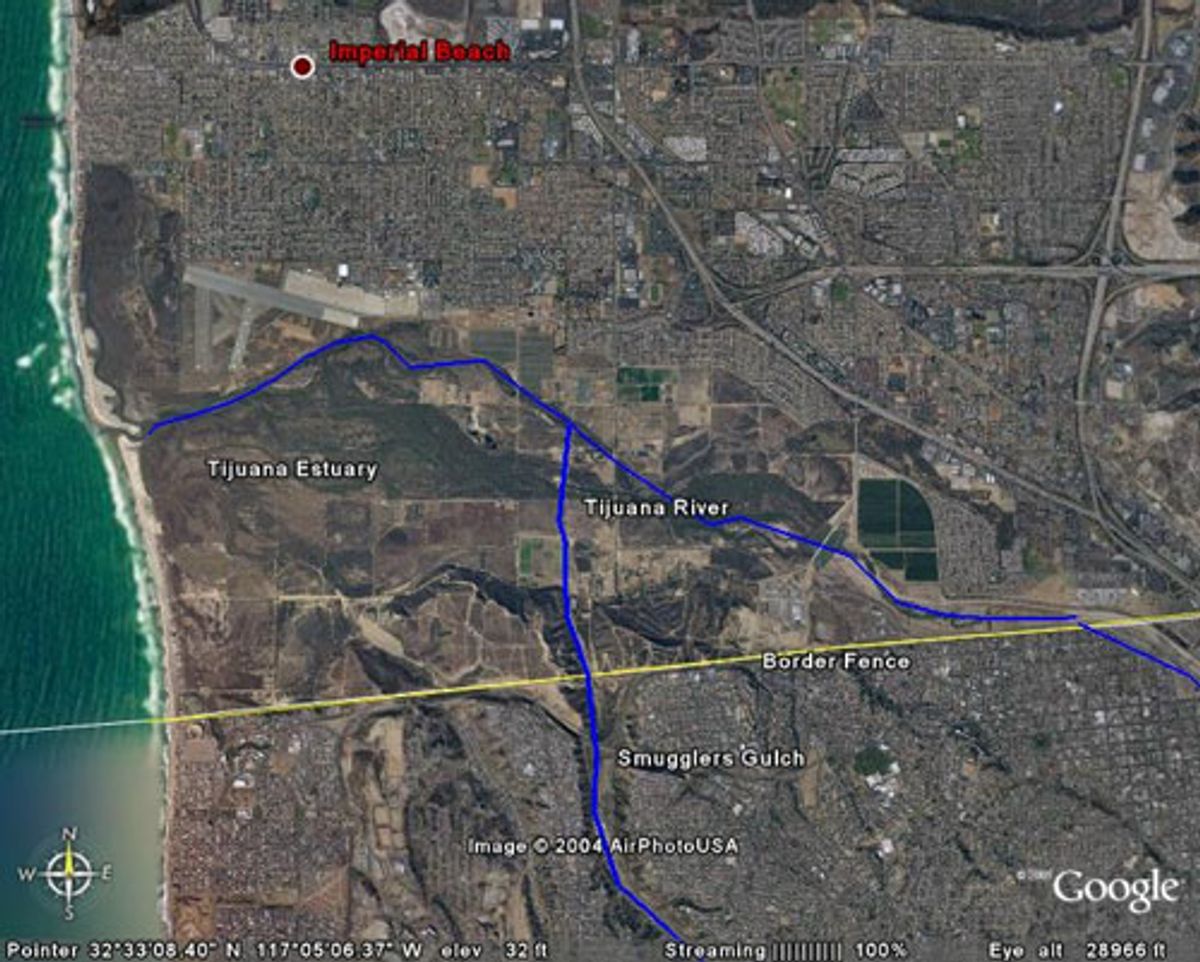

On a cloudy November morning along San Diego County's border with Mexico, the Tijuana River is a bubbling, greenish-brown stream peppered with trash. It trickles into a 300-foot gully known as Smuggler's Gulch, a well-worn illegal immigration route. Up the hill from the gulch is a dilapidated fence that continues a few miles west to the Pacific Ocean, a combination of hole-ridden rusting metal and chain-link that reaches into the water. The area isn't exactly picturesque, but this stretch of the U.S. border is at the center of a controversy pitting the Department of Homeland Security against a coalition of environmentalist groups.

Homeland Security plans to finish a job begun in 1996: building a 14-mile-long wall, 10 to 15 feet high and three layers deep, stretching east from the Pacific Ocean to the foothills of the San Ysidro Mountains. Construction on the remaining three and a half miles closest to the ocean has been held up by environmentalists, who have sued to stop it. U.S. officials say the border wall is essential for protecting national security. According to environmentalists, if the Department of Homeland Security prevails in a U.S. District Court hearing Monday, 2,500 acres of federally protected wetlands near the border could be destroyed.

In order to have the lawsuit dismissed and proceed with construction, the Department of Homeland Security is counting on the sweeping power of a new waiver passed into law by Congress in May. The waiver, part of the Real I.D. Act, allows Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff to override any law he feels stands in the way of plans for border security, without judicial review. Environmental groups say that by circumventing existing legal protections, the wall will devastate the Tijuana Estuary, home to some of the rarest plants, birds and coastal land in the country. Other opponents, including immigration experts and human rights advocates, argue that the real issue is flawed immigration policy, not terrorism. They say the wall is a waste of nearly $60 million: History has shown that walls don't work; they just push migrants into more dangerous crossing areas where they are more likely to die. If Homeland Security succeeds in having the lawsuit thrown out, critics say, it could also set a precedent with far-reaching impact.

"Homeland Security is starting with environmental laws because we stood up to them first," says Cory Briggs, the attorney representing the environmental groups in San Diego. "If our case is dismissed, environmental laws will be just the first domino to fall. The next person that opposes them on a border security issue, they'll waive other laws too."

In this case, protections from the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and the Endangered Species Act will be cast aside. "All the rules for protecting wetlands, for protecting our drinking water, are disregarded with this waiver," says Jim Peugh, Conservation Committee chair of the San Diego Audubon Society.

Homeland Security's plan includes carving off the tops of two nearby mesas, filling in Smuggler's Gulch with more than 2 million cubic yards of dirt, and building a road across it. An underground pipe will re-route a Tijuana River tributary that now flows through the area. Environmentalists say sediment from the filled-in gulch will flow into the estuary and choke the life out of it. It will also overburden a water treatment system that is already often overwhelmed with sediment during rainstorms. Homeland Security disputes those assessments, but critics say federal officials haven't taken the issue of environmental impact seriously. Andrew Collison is a geomorphologist with the San Francisco environmental hydrology consulting firm Philip Williams & Associates, which produced a review of the potential impact in September 2003. "It looked like the analysis was not very thoroughly reviewed" by government officials, Collison says. The concerns raised by the study, he says, such as rerouting of the Tijuana tributary and types of excessive erosion, were largely ignored. "They just blew it off," he says.

The California Coastal Management Program, a state agency that reviews federal activities affecting the coast, also opposed Homeland Security's plan and offered a more environmentally prudent one in Februry 2004. It was rejected. "We had many, many conversations with Homeland Security, but we couldn't convince them there was a better way for them to do this," says Mark Delaplaine, a CCMP supervisor. "When you give someone a reasonable alternative, you expect they will listen to you. But Homeland Security was just throwing their weight around, saying they could use the waiver."

The waiver was a little-noticed footnote to the Real I.D. Act, which was itself tacked on to an $82 billion spending bill for U.S. troops in Iraq. The purpose of Real I.D. was to implement some of the recommendations made by the 9/11 Commission, such as counterfeit-proof driver's licenses and tighter asylum laws. But some conservative congressional Republicans, frustrated in part by the environmentalists' lawsuit to halt construction of the wall, added language exempting the Homeland Security secretary from existing laws and the court system when it came to building barriers at the border. "Notwithstanding any other provision of law, the Secretary of Homeland Security shall have the authority to waive, and shall waive, all laws such Secretary determines necessary to ensure expeditious construction of barriers and roads," reads Section 102 of the Real I.D. Act.

"I think it's very dangerous to be suspending laws like this, using blanket waivers," says Doris Meissner, the INS commissioner from 1993 to 2000 and now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute in Washington. Waivers available on a "case-by-case basis" are more reasonable, she says. "You don't come to an accommodation by simply abandoning laws."

Proponents of the wall cite national security concerns as the top priority. U.S. Border Patrol spokesperson Salvador Zamora says agents now look at the border much differently than they did before Sept. 11, 2001. "If they can smuggle a pound of cocaine in a glove compartment, they can smuggle a dangerous chemical or a virus in, too," Zamora says. Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, a Washington think tank that supports tighter immigration controls, points to the case of apprehended Hezbollah supporter Mahmoud Youssef Kourani, who paid to be smuggled across the U.S.-Mexico border in 2001. "If a dishwasher can sneak across the border, so can a terrorist," Krikorian says.

Better fencing and deterrents like stadium lighting and surveillance cameras have brought down the number of illegal crossers in urban San Diego significantly. In 1996, when plans were first drawn up for the triple-layered wall, 6,000 people were swarming the border near the ocean each night, despite a 10-foot-high welded-steel wall in their way. More than half a million apprehensions were made annually in the San Diego sector by Border Patrol agents back then; this year the number was down to about 127,000.

But critics contend that walls only send migrants to more remote crossings. Data compiled by the Mexican Migration Project shows that in 1988 about 70 percent of all border crossings occurred either at Tijuana-San Diego, or in Texas at Juarez-El Paso, while 29 percent crossed in more remote border regions. By 2002, after the construction of walls in both places, that 29 percent figure had grown to 64 percent. Undocumented migrants simply started going around the more fortified sectors.

That has made border crossings more deadly. As the chance of getting caught has gone way down, the chance of dying while crossing is way up -- triple what it was a decade ago. The inland landscape east of San Diego is harsh and mountainous, outside temperatures range from over 100 degrees to well below zero, and there is no water. Migrants die from heat stress and hypothermia or, in trying to avoid the desert, drown in the strong currents of border canals and rivers. This year has been the worst year on record for border crossers: 472 have died as of Sept. 30, according to the Border Patrol, and 26,000 have been rescued.

"It's disturbing that, in the name of national security, a great country like the U.S. will basically force poor migrants into the desert where they will die or be at the mercy of extremely unscrupulous human smugglers," says Timothy Edgar, the national security policy counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Edgar says Homeland Security's plan is more political than practical when it comes to security. He also points to an outlandish proposal by Republican Rep. Duncan Hunter of California to build a wall along the entire 2,000-mile border with Mexico, at a cost of $8 billion. "I don't think any of us want to live behind the Berlin Wall," Edgar says. "If we have enough money lying around that we could spend it building 2,000 miles of fencing, we would be better off using it to get the FBI a decent computer system."

"The plan reflects a general frustration among our leaders in not being able to keep people out of the country that aren't here legally," says Dan Griswold, director of the Center for Trade Policy Studies at the libertarian think tank Cato Institute. "The vast majority coming here from Mexico wait tables, wash dishes, pick strawberries, do construction. They aren't terrorists."

The Pew Hispanic Center's study "Unauthorized Migrants: Numbers and Characteristics," released in June, estimates that at least 6.3 million illegal immigrants were employed inside the United States as of March 2004. About a quarter of all drywall and ceiling installers, a quarter of all meat and poultry workers, and quarter of all dishwashers are here illegally.

The Border Patrol knows the vast majority are crossing in search of jobs. "Most of those we apprehend aren't combative," Zamora says. Although walls have been successful at keeping vehicles loaded with Mexicans from driving across the border, agents admit it is not a long-term solution to immigration and security problems. "The fence might slow them down, but it won't stop them," says San Diego border agent T.J. Bonner, also a spokesperson for the National Border Patrol Council, the agents' union. If the U.S. government enforced sanctions against employers who hire illegal immigrants, Bonner says, agents' job would be considerably easier. "What we really need," he says, "is to turn off the employment magnet."

In the end, building the triple-layered wall through Smuggler's Gulch could end up striking against national security in its own right, by polluting Navy training beaches in Coronado, Calif., just a few miles from the border. The irony is not lost on environmentalists battling the plan. Sediment from the filled-in gulch will likely clog up piping that funnels polluted Tijuana River water into and out of a water treatment plant on the U.S. side of the border. When that happens, the river, carrying raw sewage from Tijuana, will empty untreated into the Pacific Ocean.

Serge Dedina, executive director of WildCoast, a nonprofit group that works to protect coastal areas, says he and fellow surfers in the area often wind up with ear and sinus infections, as well as intestinal bugs, from bacteria in the ocean water. Imperial Beach has been closed 83 days this year due to sewage contamination. The beaches in Coronado where the U.S. Navy trains have been closed 33 days. "The guys we need to train to protect our country can't train because the water is too polluted," Dedina says. "How is that helping with national security?"

Shares