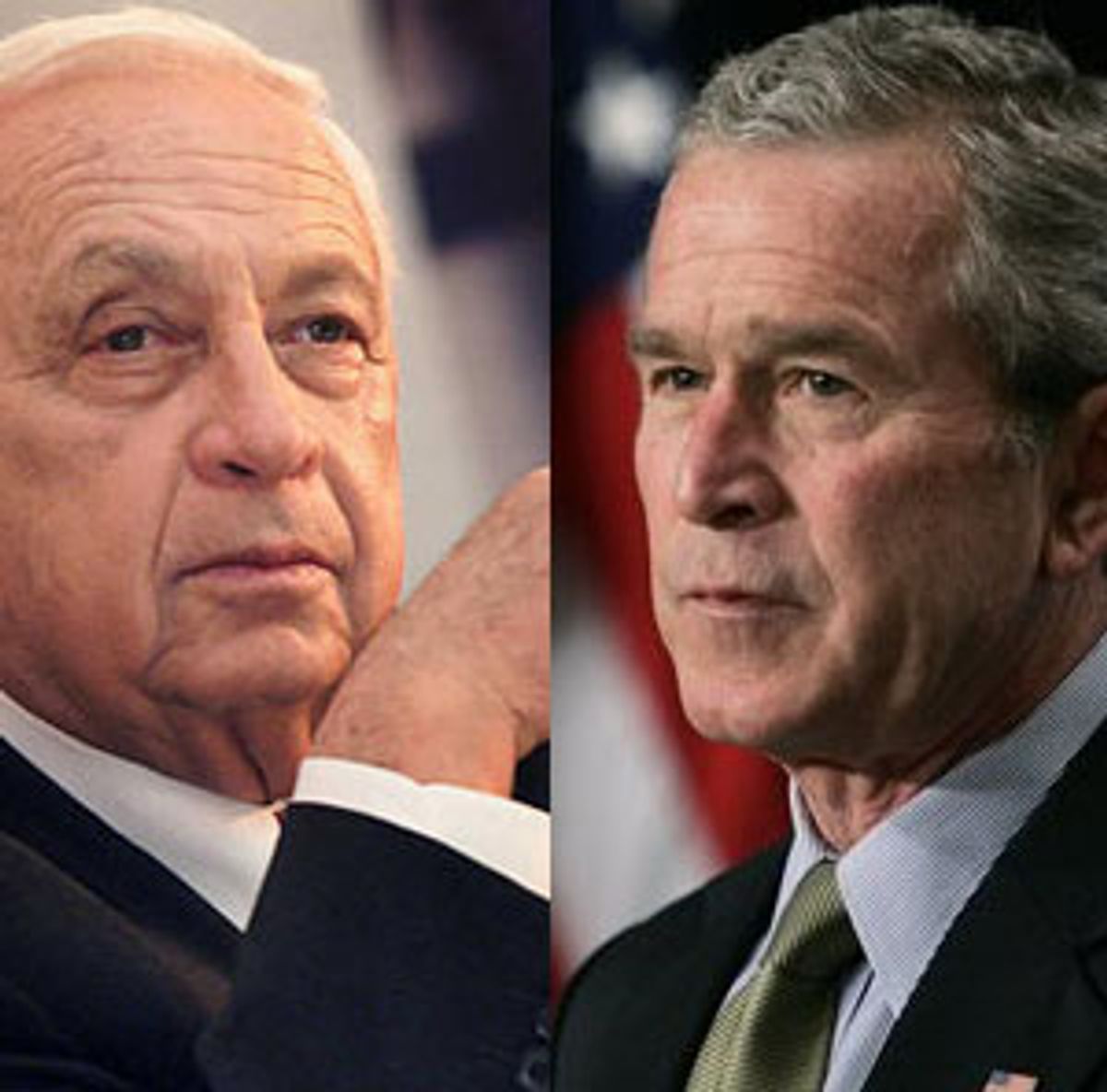

In April 2005, President George W. Bush gave Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon the most precious gift an American president can give to a foreign leader -- a visit to his home, in this case his Crawford, Texas, ranch. Bush grants invitations to the ranch to only a handful of foreign leaders. They tend to be either friends of the president, like Britain's Tony Blair, or leaders he really needs to impress, like Saudi Arabia's Prince Abdullah or Mexico's Vicente Fox. Sharon fell into a third category: leaders who need to show their people at home that the leader of the free world is on their side.

Bush gave Sharon the whole Crawford routine: a ride on a pickup truck with the president of the U.S. serving as a tour guide, playing around with Barney the dog in front of the press, and an informal, easygoing discussion Texas-style, with a lot of joking around and no neckties. Hours later, briefing the Israeli press at the nearby airport, Sharon was glowing. "It was a great meeting, a really great meeting," he said again and again, stressing how important for Israel it was to have such a good friend in the White House. The Israeli press went wild, with huge front page pictures and detailed reports comparing Bush's Texas ranch to Sharon's ranch in Israel's southern Negev region.

The spin worked. The Israeli public, encouraged by the backing its prime minister was getting from the leader of the free world, supported Sharon's disengagement plan. His popularity in the polls skyrocketed.

Peeling off the layers of P.R. and looking at the real relationship between Bush and Sharon, who is now struggling for his life in a Jerusalem hospital, it is clear that though there was no real friendship between the two men, they still managed to forge a strong relationship, one that benefited both of them politically.

Bush and Sharon could not have come from more different backgrounds. One grew up in a wealthy and privileged family, a political dynasty; the other in near-poverty in a family of hardworking farmers who couldn't even get along with their own neighbors. One did all he could to get out of military service, while the other's whole career was in the military, always in the front lines, always carrying wounds from the last war.

But there are also threads of similarity between the two men. Most significantly, both came to power as outsiders, and neither ever trusted anyone or anything in the political system. Both are polarizing figures who had to fight hard to win the support and affection of their own people. (Sharon, who won over many of his Israeli critics at the end of his life, succeeded much better than Bush, who is admired and detested in equal measure by Americans.) And both Sharon and Bush are ranchers, though neither one of them has ever actually worked his ranch.

Bush's first encounter with Sharon was dramatic. It was in December 1998 and Bush was visiting Israel for the first time with a group of Republican governors, a trip organized by pro-Israel activists in the United States. After meetings with Israeli leaders, the group took an aerial tour of Israel by helicopter. The guide was Ariel Sharon. While flying over the Green Line, marking the pre-1967 borders of Israel, Sharon lectured to Bush and his colleagues, over the earphones in the noisy chopper, about Israel's "narrow waistline," telling them how dangerous going back to the old border would be for the tiny country. Bush, used to the vast plains of Texas, was impressed, and since then he has mentioned his little tour every time he has spoken in front of a Jewish audience. The incident may have had momentous consequences: Bush signed off on Sharon's policy of "thickening" Israeli settlements in the West Bank, a major point of contention between Israel and the Palestinians.

Bush and Sharon took office at the same time, and their relationship got off to a good start. Israel was already deep into the second intifada and terror was raging, but the new boss in the White House provided Israel with at least one reason to be optimistic. In his first meeting with the National Security Council, on Jan. 30, 2001, Bush surprised members of the NSC by declaring, "We're going to correct the imbalance of previous administrations on the Mideast conflict. We're going to tilt it back toward Israel." Author Ron Suskind, in "The Price of Loyalty," his book about Paul O'Neill, describes what followed this statement: Bush asked if anyone had ever met Sharon. Secretary of State Colin Powell was the only one who raised his hand. Bush went on: "I'm not going to go by past reputations when it comes to Sharon, I'm going to take him at face value." Then he described his helicopter ride with Sharon, saying that he had flown over the Palestinian camps and that it "looked real bad down there." "I think it's time to pull out of that situation," Bush said -- meaning the U.S. would cease its active role in trying to broker a peace deal and leave it to the two sides to work it out.

Powell, according to Suskind's book, based on notes Paul O'Neill made during the meeting, told Bush this would be a dangerous move that would give a free hand to Sharon and the Israeli army. "The consequences of that could be dire, especially for the Palestinians," Powell said. Bush shrugged. "Maybe that's the best way to get things back in balance," he said. "Sometimes a show of force by one side can really clarify things."

By openly announcing a tilt toward Israel, Bush was staking out a position that broke with long-standing U.S. policy. What led him to take such an unusual position and present it in such a vigorous way? In part, it's because Bush surrounded himself with advisors known to hold stridently pro-Israeli views, most of them hardcore neocons. Paul Wolfowitz, Doug Feith, Richard Perle and Lewis "Scooter" Libby were all supporters of a strong Israel; Feith and Perle had opposed the U.S.-backed Oslo process. Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld held similar views: Cheney once said that Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat should be killed, and Rumsfeld referred to the "so-called occupied territories."

But that is only a partial explanation. Bush had seen his predecessors, Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush, stumble in the Middle East. He saw Clinton's failure at Camp David, and he remembered his father's difficult relationship with the Jewish community after he denied Israel loan guarantees because Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir would not freeze settlements. He concluded that no good had ever come to an American president from diving into the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Bush was as good as his word: He tilted toward Israel and gave Sharon a blank check to do what he wanted in the occupied territories. Bush did not pressure Israel on issues of settlements and illegal outposts, he did not pay much attention to the humanitarian crisis caused by Israeli roadblocks and closures, and he brushed off calls to reprimand Israel for using U.S.-made F-15s for targeted killings.

The relationship between Bush and Sharon was cemented by the 9/11 terror attacks. Bush divided the world into those who fight terror and those who support it. For Bush, Sharon's Israel was the good guys and Yasser Arafat's Palestinian Authority was the bad guys. "9/11," says former ambassador to Israel Daniel Kurtzer, "added the emotional dimension to the Bush-Sharon relationship." Now they were both in it together, fighting terror.

There were, however, some rough spots in the early years of the Bush administration. After the 9/11 attacks, as Bush tried to build a coalition of moderate Arab states, Sharon became afraid that Bush was departing from his hands-off approach and caving in to Saudi pressure to present a peace plan and demand Israeli concessions. Sharon lost his cool, and in a speech delivered both in Hebrew and in English warned America not to try to "appease" the Arab world at Israel's expense. "I turn to the United States and say don't go back on the same mistakes as the democracies made in 1938. That is when Czechoslovakia was sacrificed for a convenient, temporary solution. Do not appease the Arabs on our account. Israel will not be Czechoslovakia. We will defend ourselves." The U.S. in turn denounced Sharon's angry remarks as "unacceptable." But it turned out to be an isolated event. Sharon worked quickly to fix the relationship and the incident was forgotten.

Sharon, for his part, made every effort not to harm his relationship with the White House. Powell's fears of "unleashing" Sharon turned out to be exaggerated. The new Sharon who came to power in Israel was quite different from the Sharon Powell had in mind. He was still a hard-liner, still tough on terror and still blind to human rights issues, but at the same time Sharon understood that his success in Israel depended on maintaining a good relationship with the U.S., and for that cause he was willing to do a lot.

In March of 2002 the Israeli army embarked on a major incursion into the West Bank, called "Operation Defensive Shield," in response to an upsurge in Palestinian terror attacks, including the Passover massacre in Netanya that killed 30 people who were celebrating the Jewish holiday. Sharon ordered the army to do what it had not done for a decade -- enter all Palestinian cities and camps with full force. Sharon did not seek Bush's early approval for the operation and the U.S. did not try to stop him.

The way Bush and Sharon handled Israel's incursion into Palestinian cities was typical: Bush let Sharon do as he pleased up to a certain limit, and Sharon knew when it was time to stop in order not to embarrass his American friend. A week into the operation, with Israeli troops in all West Bank cities and on their way into the refugee camps, Bush said "enough is enough." Asked when Israel should withdraw, he replied, "As soon as possible." Sharon did not budge. He knew that Bush was only paying lip service to the international community and that the U.S. president knew very well that Congress supported the Israeli operation. The Israeli forces kept moving in and the U.S. did not insist. Bush and Sharon talked by phone and Sharon said it was too early to pull back the troops. Bush, according to Israeli sources, gave a vague response, which Sharon understood to be an approval to continue.

Three days later Bush said publicly, "I meant what I said," and Sharon finally moved some forces. Sharon sensed that Bush needed him to begin to withdraw, so he did, but he also knew that the American president required only a token gesture. Sharon withdrew, slowly, from cities where the operation had already ended in any case; he left forces in the major terror hot spots of Jenin and Nablus. As always, Sharon's between-the-lines reading of Bush's desires was correct: The White House was satisfied with the partial withdrawal and didn't ask for more.

The only one who wasn't aware of the tacit understanding between Bush and Sharon was Secretary of State Colin Powell, who was dispatched to the region to, he believed, broker a cease-fire and bring the sides to an international conference. While Powell was working to convince Sharon that there was a chance for negotiation, Bush and the Israeli leader had already agreed that Arafat was out of the game and that there would be no international conference.

Before becoming prime minister, Sharon had a difficult history with American officials. After the Sabra and Shatila massacre in 1982 and the Kahan commission that put part of the blame on Sharon, at the time the minister of defense and the architect of Israel's invasion of Lebanon, the U.S. would have nothing to do with him. Sharon became a persona non grata in Washington and around the world. But it wasn't only the Lebanon war. In the years after the war Sharon was seen by Americans as the driving force behind the settlement activity and was criticized for the role he played in building new settlements.

Sharon's rehabilitation process began only when George Bush took office -- but it didn't take long. Bush not only agreed with Sharon on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but he also grew to like him personally. Officials who attended the meetings between Bush and Sharon (Sharon was invited to the White House more often than any other world leader) described a pattern: In the first meetings Sharon would lecture, talk about Israel's difficult situation and exhaust the president with intelligence details on Palestinian terrorism and the role of Yasser Arafat in initiating it. But as the two leaders got to know each other better, Sharon felt more comfortable -- he tried to joke around, talked about his political situation and gave up the long lectures. They never became buddies, says an official who attended most of the meetings, but the atmosphere was pleasant.

Sharon's decision to avoid conflict with America paid off. He not only enjoyed a free hand in dealing with Palestinian terror, but also got from George Bush more than any other Israeli leader has ever gotten -- a written American consent to keep Jewish settlement blocs in the West Bank under Israeli control in any future peace agreement.

On April 14, 2004, Sharon came to the White House to discuss the final draft of his Gaza Disengagement plan, which would dismantle all Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip, pull out Israeli military and give Gaza back to the Palestinians. Sharon told Bush it was a historic move, that no other Israeli prime minister had ever removed settlements, that the Israeli people would have a hard time approving the plan without getting something in return. When the two leaders met with the press in the East Room they could already present the American response to the plan: A letter from Bush to Sharon (ironed out days before by Condoleezza Rice and Sharon's advisor Dov Weissglass) stated that because of "new realities on the ground, including already existing major Israeli population centers, it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be a full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949." The letter also stated that Palestinian refugees should be settled within the future Palestinian state, not in Israel. The exact wording was a little vague, but it was enough for Sharon, who could now sell his plan to the Israeli people, saying that in return for giving up the Gaza Strip, Israel could keep the big settlements in the West Bank and didn't have to worry about the refugee issue.

For Sharon, Bush really was at that moment Israel's greatest friend -- and the Israeli public agreed. A poll conducted in October 2004 in 10 countries around the world found an overwhelming majority of respondents who wanted to see John Kerry win the U.S. presidential elections. Only two countries preferred Bush: Israel and Russia.

Bush himself also had a lot to gain from his good relationship with Ariel Sharon. The American Jewish community, which gave him only 19 percent in the 2000 elections, began to see him as a strong supporter of Israel and in 2004 he was up to 24 percent. More important, he was able to attract much more Jewish money for his campaign, money that in the past would never have gone to a Republican candidate.

Bush's standing by Sharon also helped him with the influential Christian evangelical community. Bush shares the religious views of the evangelicals, and also sees them as an important part of his success. According to press reports in Israel and the U.S., Karl Rove, Bush's top political advisor, convinced the president several times not to pressure Israel into concessions, fearing that it would cost Bush the support of evangelicals, who believe that Israel should hold on to greater Israel until Kingdom Come.

The support he gave Sharon benefited Bush in another, subtler way. It served to improve Bush's image in the U.S., not just among evangelicals and Jews but also across the political spectrum. The Israeli war against Palestinian terror was always more popular than America's war against global terrorism, and Bush's partnership with Sharon allowed Bush to take advantage of that without paying a political price: For Democratic and Republican politicians alike, unswerving support for Israel is a given. By supporting his Israeli counterpart, Bush said in effect, "If you like Sharon the tough guy, you can like me too. I'm his friend, we're both in it together."

Shares