Nobody would mistake left-wing scholar and publisher James Weinstein for Roger Ailes. But long before there was a Fox News, Weinstein knew that the failure of the American left to become an enduring force in American politics was in part a failure to compete in the marketplace of ideas and in the world of media -- and that back when the left thrived, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it relied on a web of local, regional and national newspapers and magazines. So while most of his colleagues focused on their books and the world of academia, he played a leading role in founding journals like Studies on the Left and Socialist Review, starting San Francisco's Modern Times bookstore and, most notably, In These Times newspaper.

I worked at In These Times in the mid-1980s, back when it called itself "an independent socialist newspaper" (being more honest about his politics than Roger Ailes, Weinstein didn't choose the motto "fair and balanced"). I saw the label as one of Weinstein's charming eccentricities -- he was determined to revive socialism's respectability, take it back from those who had stolen it -- but the paper's left-wing politics were not eccentric; it was unexpectedly hardheaded. That was where I lost my romance with identity politics, with believing that some amalgam of women, blacks, gays and other pissed-off people would gradually rise and transform American politics. The paper covered all those movements, but critically. And it backed efforts to work within the Democratic Party, like Jesse Jackson's 1984 and 1988 presidential runs, discouraging the vanity and nihilism of third-party politics -- the impulse that ultimately turned into Ralph Nader's disastrous Green Party run in 2000, which gave the presidency to George Bush.

Weinstein knows disastrous third-party efforts firsthand -- he was a Communist Party member for a short time in the 1940s, and became briefly infamous on the left in the late 1970s for helping to confirm historian Ron Radosh's revisionist account of the Rosenberg case: that despite the left's claims that Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were falsely accused and wrongly executed for spying for the Soviet Union, Julius did in fact pass information to the Soviets. (He also favorably reviewed Radosh's "The Rosenberg File" for In These Times.) To many on the left Weinstein's admission was heresy, given the history of redbaiting and right-wing witch hunting the left had endured in the 1950s. But Weinstein has always reckoned clearly with the contradiction of that decade -- redbaiting was a disaster, but so was communism, and both had hurt the American left.

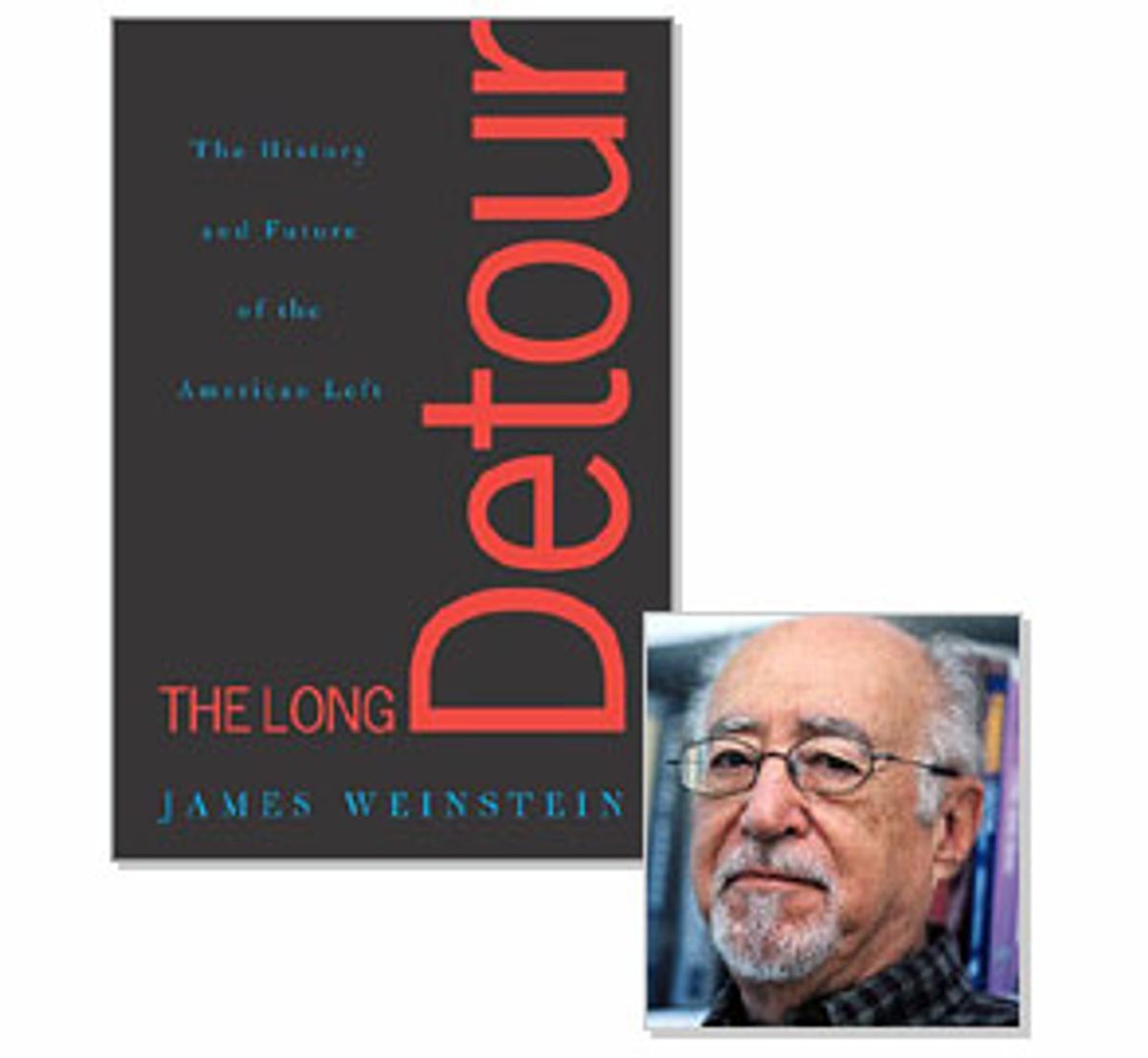

Weinstein retired as publisher of In These Times in 1999, though he still supports its work, and this year he finished his fourth book, "The Long Detour: The History and Future of the American Left." He calls himself a "pathological optimist," and he thinks that despite its "long detour" -- the Soviet experiment and the years American communists spent defending it -- the left can once again play a vital role in reforming American democracy. Salon spoke to Weinstein by phone from his home in Chicago.

Your book charts the development of an authentic, indigenous, vital American left -- and an American socialism -- through the beginning of the 20th century. Then it all came apart with World War I, when the left's opposition to the war was used to tar it as treasonous and anti-American, and there were a whole string of government efforts to target and dismantle it. Was that really the first time the left was attacked as "traitorous"? Obviously, there are echoes today.

Well, it was, really. Before that, there were some movements and groups that were attacked as "un-American," given the prevalence of immigrants in their ranks. But not "anti-American" or treasonous. Still, the socialists gained a lot of support during the war, in fact, that led to the government's efforts to disrupt the party. It's hard for people to understand today how unpopular that war really was.

Yes, it's linked with World War II as one of the "good wars."

Right, but it was very unpopular at the time, and one big factor was the number of German immigrants in the U.S., many of whom did oppose the war ...

For nationalist reasons.

Some of them. But not all of them. Of course, the German socialists -- who were particularly powerful in Wisconsin, especially Milwaukee -- were totally anti-Kaiser. They didn't oppose the war because they supported the Kaiser.

But they were smeared that way.

Yes. Then later, with the rise of the Soviet Union, the left was considered "anti-American" because it was seen -- the Communist Party, at least -- as supporting an enemy that was supposed to be very powerful and threatening, but that was basically weak and desperately trying to catch up with American capitalism's level of industrialization.

But you've always been very honest about the fact that the American Communist Party was supporting the Soviet Union, which was our enemy, and how that support completely disfigured the American left, with ramifications to this day. In fact, reading the book I found myself going back and forth between feeling like the left has been destroyed by the government -- looking at World War I, the Red Scare, the Palmer Act, McCarthyism, through COINTELPRO in the '60s -- and the notion that the left has destroyed itself. Thanks to its romance with the C.P. and the Soviet Union in the '40s and '50s, and then with violence in the '60s. Where do you come down on that question?

Look, I wrote this book to make clear that, as you say, there was an American left, an American socialism, and through the first 20 years of the 20th century, it was growing and important. Much of what it advocated for we take for granted today. Especially after the New Deal -- Social Security, workmen's compensation, unemployment insurance, the eight-hour workday, the 40-hour week, minimum-wage laws -- the ideas of the left became mainstream ideas. But they started out as totally marginal. You also have to understand, the left was in every aspect of American society back then: Two-thirds of the original members of the NAACP were socialists. The first people who got arrested for advocating birth control -- Margaret Sanger, etc. -- were socialists. Many trade unionists were socialists. The Intercollegiate Socialist Society, the children of the ruling class, was a vigorous organization. It had become an important aspect of every part of American life, and its programs addressed the problems of the emerging gigantic corporations -- it was an attempt to stabilize the system, which meant to humanize it.

So as time went on, and especially in the New Deal, the ideas that had originally been totally marginal became the property of the mainstream of American political discourse, and meanwhile socialists had nothing new to say, because the Russian Revolution had thrown the whole movement backward. What came to mean "socialism" after the Russian Revolution was this incredibly backward, pre-capitalist, pre-industrial society whose main goal was to catch up with the west. I mean, in my book I show how the Russian city of Magnitogorsk became the model of a socialist city, but it replicated Gary, Ind. -- everything radiated out from the steel mill! -- which was probably the worst failed American city. I mean, they had no idea what socialism was. It was a terrible throwback, the use of slave labor, the absence of any kind of political democracy. And yet the communists, who really were at the time the most vital force in the American left, were defending it.

Yeah, but that goes back to my question: Was the left destroyed or did it destroy itself? I mean, the party channeled that vitality toward defending this failed system -- which offered no democracy plus a lower standard of living. Great idea, sign me up.

Right. And coming out of World War II, you had American society going through tremendous changes, and you had corporate rulers worried we might fall back into the Great Depression. Their answer was partly the Cold War, and partly consumerism -- we go from a society built on self-abnegation and saving money to a society where everybody moves to the suburbs, everybody has two cars, everybody needs their own washer/dryer -- but the left had no answers. There was really very little in the way of an attempt to make sense of it.

In fact you had this odd break after the bitter infighting around communism and McCarthyism -- and then came the New Left. And I'm struck, in the book, by what you say the New Left had in common with the way the Communist Party worked -- that the emphasis on identity politics seemed borrowed from Popular Front-ism (when communists advised members to work through existing organizations to try to move them left). In both cases, there was no focus on cross-issue politics, on class, there was no overarching ideology -- the communists because they didn't want to be honest about what it was; the New Left because it really didn't have one. And they were both dead ends.

I love the story I use in my book about [leading antiwar activist] Jerry Rubin, because it encapsulates what the problem was. Here you had this great antiwar movement, where most people who got involved were in it because they wanted to end the war, but when someone suggested they might actually end the war, Jerry Rubin panicked: "What would happen to the movement?" he wanted to know. His private belief was that this was some kind of revolutionary moment and that it couldn't just "succeed." But this was true of a lot of people in SNCC [the Students' Nonviolent Coordinating Committee], the environmental movement.

I think it's true to this day. I think a lot of people on the left who get involved in single-issue movements -- antipoverty movements, welfare organizing, labor, education reform -- have this nihilistic belief that they can't really solve the problems they're purporting to address, because "the system" is so corrupt it won't let them. If they did their jobs as advocates successfully, the issues would go away and they wouldn't know what to do with themselves.

Yes, there's some of that, and even worse than that is every one of these movements begins to operate not as part of a coherent left, as it did in the early 1900s. All these movements existed, but they were all held together by common goals and principles of the socialists who were the dominant force on the left at that time. Today, they all become like any other lobby group, and they become more and more narrow ...

And there's a zero sum approach, where if Latinos get some, blacks get less, if women get better jobs, men have to lose.

And yet, the left still has this approach to politics where they talk about coalitions as laundry lists of organizations and groups whose basic approach is really divisive.

There's no vision of a common good.

Right. And with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, it should have been possible to put that whole period behind us and start thinking: Now, what's a left that works in this country? What is the potential in the United States for the kind of society that would let us all lead humane, comfortable, secure, creative lives? But it's not happening.

Anywhere?

Nowhere!

Well, you've always been a comparative realist on the left, and negative about the potential for third parties, given our "winner take all" system. In These Times sponsored a lot of debate over the Nader campaign, but I know you were very critical of it yourself.

I was very critical, but of course we were open to our readers' opinions and we had a lot of readers who just loved Ralph Nader. And it isn't even a question of Ralph Nader. Right now Nader is working with Dennis Kucinich, who's running in the Democratic Party.

Which is what you think he should be doing?

Well, not necessarily. Look, I've been criticized for saying everybody should rush and join the Democratic Party. That's not what I'm saying. I think there might be congressional districts where you can do something different. I think there are congressional districts where the left should run somebody in Republican primaries. My real model is the Non-Partisan League, which was in neither party, but which got control of all of North Dakota with allies in both parties, because it utilized an open primary system. Whereas the Socialist Party, which had the same exact platform, never elected anybody except in a couple of districts.

But the problem with the Green Party is that it doesn't tend to run in Republican districts or challenge Republicans. It looks for places where it's got some strength -- which tend to be places that elect Democrats. So they go up against Democrats.

And they split the left.

But supporting Kucinich is a step in the right direction.

Yes. I mean, Kucinich isn't going anywhere. That's not the point. The point is that Kucinich is doing in the Democratic Party something that's analogous to what Nader did -- he's getting some large crowds, he got 10,000 people in Minneapolis, and they're hearing his ideas and they're getting excited. I think he's bringing people into the process. And then when he's forced out, they have the option of hooking up with someone else because he's doing it within the Democratic Party framework.

You talk about Ralph Reed in the book -- he's your role model, right? But seriously, he goes from Christian Coalition head to take over the Georgia Republican Party and takes down Sen. Max Cleland. The Christian right has a lot of discipline that the left just seems to lack.

They've done very well. They still don't represent more than 15 to 17 percent of the voters. But because they operate intelligently, unlike the left, they have tremendous influence.

So you're supporting Howard Dean this year.

Oh yeah, I mean, I don't think he's Franklin D. Roosevelt, although Roosevelt ran as a conservative in 1932, but he's just head and shoulders above everybody else. He's the only person who can talk to an audience and sound like an honest person, and I think that's what Americans are dying for -- someone who'll listen to what they say, respond honestly and directly, and if he disagrees he'll say why. I've heard him do that -- I went to a fundraising party for him in Chicago a couple of months ago. The amazing thing about that was that I thought I'd go see a lot of my friends, and there were 500 people there and I didn't know a single person. This is a movement.

What happens to it if he doesn't get the nomination?

Who knows? But you know, it's not that kind of movement. It's not just about him. But the war is very important. He opposed the war at a time when it was very difficult to oppose the war, and now everybody's trying to half-jump on his bandwagon. And they all look like a bunch of fools by comparison.

What do you think of the Wesley Clark phenomenon?

I think it's the Clintons' attempt, and the Democratic Leadership Council's attempt, to hang onto the party. I think they're afraid of what Dean represents -- a whole new circle of people who threaten their hold on the party. Plus I actually think Clark is a terrible candidate. Everybody thinks the Democrats need a general, but by the time the election comes around in a little over a year George Bush will be paying for Iraq, and he'll be in trouble no matter who he faces.

You think that's the issue that can bring Bush down?

Well, not necessarily. The economy's in pretty bad shape, too. [Laughs)] But I think the war is an issue that's going to mobilize and energize a lot of people.

But won't it divide a lot of people? I mean, there was a big antiwar demonstration last weekend, but the call was "End the occupation now" and I can't support that -- and most Americans won't support that.

No, we can't get out now in the sense that tomorrow morning we get out. Dean isn't calling for that.

No, but some people on the left are. Kucinich is, ANSWER is. I mean, to go back to your book, to the extent the war poses an opportunity for the left, it poses a huge danger, too.

If there were a left, which there isn't. There is no left.

Come on, there's a left.

No, there are leftists, there are little groups of leftists. But there's no left in the sense that there's any coherence or commonality ...

Well, the people with the biggest mouths get defined as the left.

Yes, and look, the "Get out now!" faction isn't necessarily bad, as long as it's in the background. It's sort of how I feel about Kucinich -- I'm glad he's there, he energizes people who aren't energized, and he provides a buffer for Democrats who know they can't slide too far to the right, they can't ignore the left.

Maybe I'm not as sanguine as you. I think the "Get out now," ANSWER people wind up getting defined as "the left" -- and the rest of us get smeared. When in fact there are really two lefts in this country. One is the optimistic one, which believes that its principles are in accordance with American democracy, that we're just trying to make America live up to its own principles. And the other is a deeply negative and pessimistic left, which really does seem to hate this country and thinks everything it stands for is wrong, that it's just a failed enterprise. That's the ANSWER faction, and it bothers me.

Well, it's really a holdover from the whole Soviet period. But it's fading.

I hope so. But then, you've always been an optimist. What makes you optimistic lately?

I was just reading an obituary for Edward Said in the London Review of Books, and it talked about how he was always optimistic, but realistic, and it quoted [the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio] Gramsci, you know, about needing a "pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will." I mean, look at what we had in this country in the 1950s, and look at what we have now. Look at the status of women, blacks, gays. And we achieved this in decades when, except for the period of the New Left in the '60s, the nation was mostly controlled by conservatives. You hear people in different movements saying how bad things are, "We haven't won anything," but that's crazy. Look at gays -- look at television, where you have shows like "Will and Grace," or the gay guys who make over the straight guys. Come on, look, it's a different world, it's a better world, despite the fact that the Christian right is built on opposition to this stuff. So that's what makes me an optimist. It's a different country, and a much better country. I'm not a historical determinist, but on the other hand, the older I get, I'm close to it.

Shares