The result of Saturday afternoon’s cloture motion on the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell” will probably be a source of bafflement to future generations studying the issue: You mean that in December of 2010, they will marvel, 33 members of the United States Senate were still so adamantly opposed to the idea of gays and lesbians serving openly in the military that they tried to filibuster it?

It’s true, but this is how it always goes with social progress, at least when it’s left to the legislative branch. It wasn’t until more than 90 years after the end of slavery that an actual civil rights bill made it through Congress and into law. And even though polls have shown Americans increasingly and overwhelmingly comfortable with allowing gays to serve freely in the military, it wasn’t until Saturday that Congress finally got around to doing anything about it.

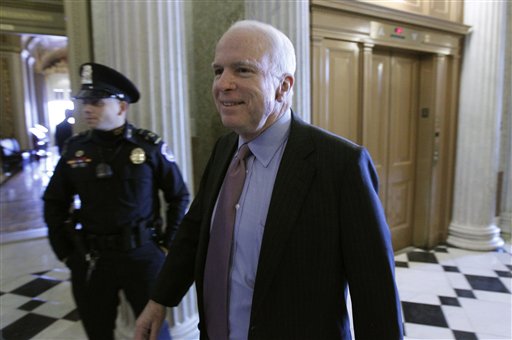

The miracle, though, is that DADT is ending at all. It looked last week as if Republicans, led by John McCain, would succeed in running out the clock on repeal for this congressional session. Senate Democrats, for the second time this year, had fallen a few votes short of the 60 needed to break McCain’s filibuster, and with a far more conservative Congress set to convene in January, DADT seemed likely to stand for years to come. And yet, this afternoon, 63 senators voted to end another filibuster, paving the way for the repeal to finally make its way to the Senate floor, where it was approved on a 65-31 vote. What changed? Well, for one thing, Democrats abandoned their too-cute-by-half strategy of gluing repeal to the Defense Authorization bill. The idea was that Republicans, nervous that a vote against the broader package might be seen as a vote against the troops, would be cowed into going along with repeal. This never came close to working, not surprisingly. It also helped that President Obama’s compromise on the Bush tax cuts worked its way through the Senate and House quickly; the small but pivotal bloc of moderate Republican senators who claimed to support repeal had been joining their GOP colleagues in refusing to take action on anything until the tax issue was resolved. Once it was, their bluff was called.

By Friday, it was clear that the new stand-alone repeal bill had over 60 supporters — the first time in the 17-year history of DADT that this had ever been the case in the Senate — and when the cloture motion was made on Saturday, 63 senators voted to kill the filibuster. DADT was as good as dead. In a matter of days (if that), President Obama will sign the bill, which cleared the House earlier this week, and fulfill one of his major campaign promises — one that some of his liberal critics had accused him of shirking.

Obama, it should be said, played this issue remarkably well. To listen to his liberal critics (at least before today), his handling of DADT has encapsulated all that’s wrong with his presidency. He’s lacked, in their telling, both a meaningful strategy and the stomach for a fight with Republicans. But the course he pursued actually made a lot of sense, as Saturday’s vote attests. Obama took pains to get Pentagon and military leaders aboard, commissioning an exhaustive study of the issue and promising them he wouldn’t preempt it with an executive order or legal fight.

While it was slow, the beauty of this process was that the final report, released three weeks ago, completely and authoritatively dismantled every rationalization that opponents of repeal could offer. The few moderate Republicans in the Senate who were open to repeal — either because of their own consciences or because of political dynamics in their home states (or both) — had nothing left to hide behind. Remember, it was only after the report’s release that Scott Brown and Lisa Murkowski finally came on board. (The same, for that matter, was true for conservative Democrat Mark Pryor.) For the past two years, Obama has loudly insisted that he was working toward repeal. Saturday demonstrated that there was a method to the madness.

Obama, of course, is far from the only leader who deserves credit. Others who did significant work:

Joe Lieberman: The stand-alone bill was his handiwork. Lieberman and Susan Collins introduced it as soon as the GOP’s filibuster of the Defense Authorization bill succeeded last week. Lieberman played a key role in reviving the repeal effort when it appeared dead. And he has been a long-standing advocate for ending DADT. That said, it’s hard to believe electoral politics weren’t partly at work: Lieberman’s reelection prospects for 2012 are grim. His activism may have been designed to win back badly needed Democratic goodwill. Whatever his precise motives, though, Lieberman played a pivotal role in dismantling DADT.

Collins, Brown, Murkowski, Olympia Snowe, Mark Kirk and George Voinovich: The six Republican senators who broke with their party and backed cloture on Saturday. Collins, to her credit, was there first; she voted for cloture on the Defense Authorization bill last week, too. Kirk and Voinovich were the late(est) arrivals; they didn’t reveal their intentions until it was clear the repeal side had 60 votes. It’s also worth noting that Voinovich is retiring in two weeks; he never took a position on this issue when an election was at stake. Still, history will record that when DADT was finally repealed, he and five other Republicans were on the right side.

Kirsten Gillibrand: New York’s junior Democratic senator had a clear selfish motive for throwing herself into the repeal fight nearly two years ago. She had just been appointed to the Senate after racking up a conservative (at least by the standards of New York Democrats) voting record in the House. Desperate to stave off a primary challenge in 2010, she turned to DADT as a means of winning over skeptical Democrats. In the summer of 2009, she convinced the Senate Armed Services Committee to hold hearings on the issue for the first time since 1993 and has played a significant role in keeping DADT on the agenda since then.

Bill Clinton: The president on whose watch DADT was enacted actually deserves credit for this moment. Remember that Clinton was forced into DADT only after his initial efforts to do away with the military’s ban on openly gay service members was met with stiff and often-hysterical resistance — from Republicans, from military leaders (including Colin Powell) and even from his fellow Democrats. DADT, as flawed as it was, represented the first step away from an outright ban on gays in the military. From then on, the debate wasn’t over whether gays should be allowed to serve, but whether they should serve openly.

Lest we forget, there are villains in this episode — plenty of them. The 33 senators who voted to keep repeal from even coming to a vote all deserve their share of derision, but none more so than McCain.

As has been the case throughout his career, it’s hard to believe that the Arizonan’s opposition to repeal was motivated by much more than spite. Repeal was championed by Obama, the man who beat him in 2008, and was a cause dear to liberal activists and many media commentators — folks McCain had considered allies before he veered hard to the right to run for the GOP’s nomination in 2008.

Just as McCain set out in 2001 to make George W. Bush’s presidency as difficult as possible after Bush had beaten him in 2000, McCain has dedicated himself to undermining Obama at every turn. Thus did the same McCain who once claimed he’d be fine with repealing DADT if the military’s top leaders were find himself on the Senate floor Saturday casting a vote that will forever more keep his name on the wrong side of history.