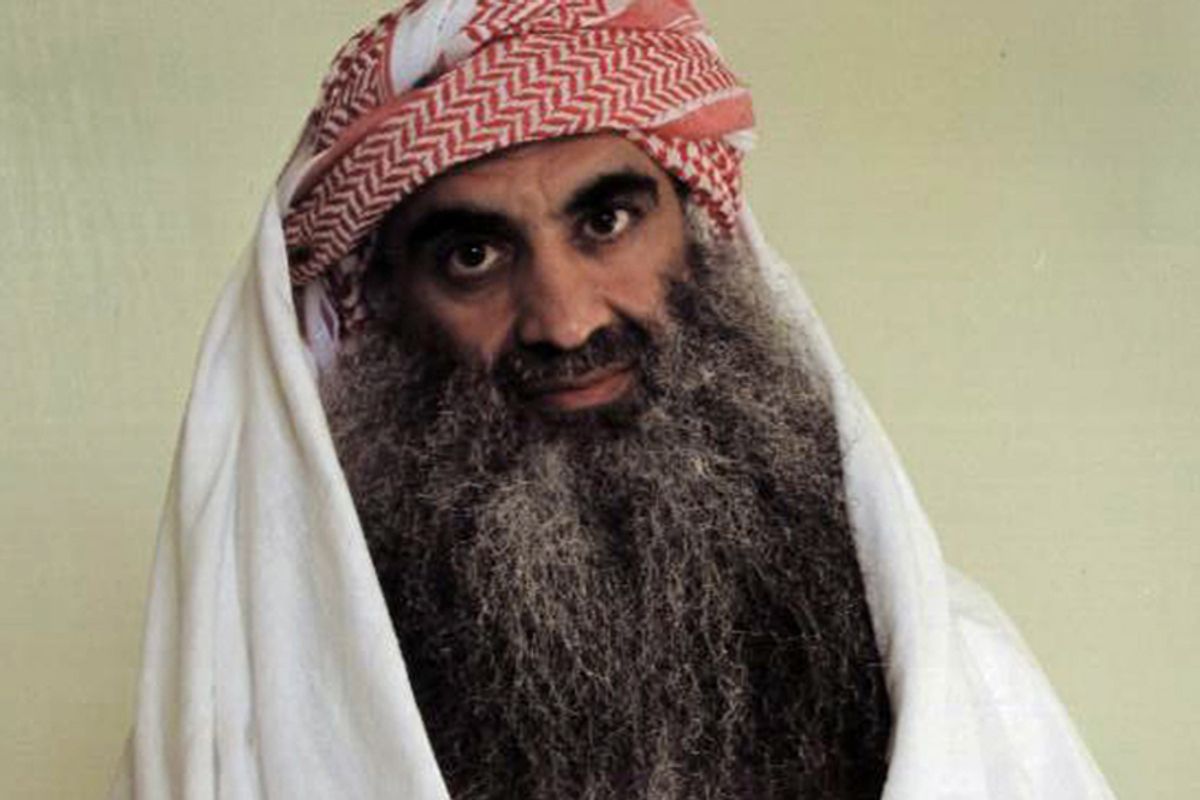

There are times in life when you don't want to hear, "Well, this will be a learning experience for us all." Open-heart surgery. In-flight emergencies. Repairing your Toyota. So what about the most important terrorism trial in United States history? Incredibly, there is a noisy political debate about whether to entrust the still-pending 9/11 trial to a military commissions system that, among its many flaws, is untested, likely unconstitutional, and has yet to demonstrate a single, credible result. Sen. Lindsey Graham now proposes legislation to bar a federal court prosecution of alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. That is a profoundly ill-conceived idea.

Whether we are at "war with terror" or at work destroying a ring of criminal terrorists, it makes sense, as a matter of national security, to use the right tool for the right job. Military commissions are not that tool. They are a legal experiment that the Supreme Court has rejected at every turn. Even presiding military Judge Col. Ralph Kohlmann derided the Guantánamo 9/11 proceedings as "a learning experience."

The commissions are now in their fifth incarnation. Hastily conceived after 9/11, they were repeatedly revised by Presidents Bush and Obama, and by Congress. Under the most recent version (the Military Commissions Act of 2009), the Department of Defense has yet to even devise rules for these proceedings. It remains unclear whether commission defendants could plead guilty to capital charges. In fact, no version of the commissions has ever tried a murder case to verdict, never mind a case approaching the importance and complexity of the 9/11 trial. If insanity is repeating the same act and expecting a different result, the attempt to install another commissions system is a textbook case.

Add to this uncertainty the constitutional cloud lingering over critical legal issues like the use of hearsay and evidence obtained through coercion, the legitimacy of using a war court for offenses that the Department of Justice concedes are not war crimes, and the adequacy of the to-be-determined trial procedures. These issues are unique to the military commissions, and they will provide convicted defendants with multiple grounds for appeals. The resolution of these issues will not be speedy. They will grind their way to the Supreme Court only after years of avoidable litigation.

This latest attempt to rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic actually complicates the legal process. It adds a layer of appellate review that does not exist in Article III federal courts or military courts-martial. Before the D.C. Circuit or Supreme Court could entertain an appeal, a third, brand-new appellate court called the Military Commissions Court of Review would have to weigh in. And when the Supreme Court finally hears a challenge to the commissions' constitutionality, it may well overturn any conviction. If swift and certain justice is important to our national security, then using this Rube Goldberg-style system of criminal justice is ludicrous.

By contrast, federal courts are a constitutionally sound forum for prosecuting terrorists. There would be no threshold question about the court's legitimacy, no grounds for appeal challenging the fundamentals of the system. And compared to the glacial pace of military commissions, a federal court trial would proceed pursuant to established standards designed to move cases forward in an orderly fashion. Federal courts are not only capable of handling complex terrorism trials, they are better than military commissions at doing it.

According to a new report by the NYU Center on Law and Security, the Department of Justice has successfully prosecuted more than 150 terrorism cases since 9/11, securing an average sentence of 16 years. As Colin Powell explained on "Face the Nation," the military commissions are a failure by comparison: "In eight years the military commissions have put three people on trial. Two of them served relatively short sentences and are free. One guy is in jail ... So the suggestion that somehow a military commission is the way to go isn't borne out by the history of the military commissions."

Professed concerns about leaks of classified information are a red herring. The 2009 Military Commissions Act adopted, nearly word for word, the same mechanism for protecting classified material used in federal court. Known as the Classified Information Procedures Act, these laws are time-tested and effective. An oft-cited but misinformed counterexample is that Osama bin Laden first learned that he was wanted by the U.S. from a document produced during a 1995 trial. As Eric Holder testified before Congress, that document was not classified, and prosecutors in that case did not attempt to protect the document from release by using CIPA. The strength and success of CIPA in federal court is precisely why Congress chose to adopt it for the military commissions.

The objection that a civilian trial would give Khalid Sheikh Mohammed a soapbox from which to spew his hateful rhetoric is simply false. Federal judges have no patience for courtroom outbursts. Witness the federal trial of Zacharias Moussaoui, the so-called 20th hijacker. His outbursts and anti-American insults led the judge to revoke his status as a pro se defendant, effectively silencing him for the duration of his trial. By contrast, the military judge at Guantánamo once invited all five of the 9/11 defendants to give a five-minute tirade before the media and victims' families just to coax them into the courtroom.

In short, using our federal courts is being tough on terror. There is plenty of risk but no discernible benefit to trying the 9/11 defendants in an untested system. This trial should not be a "learning experience." Too much is at stake for our national security, our values, and our future.

Lt.Col. Darrel Vandeveld (U.S. Army, Ret.) is a former Guantánamo prosecutor. Joshua Dratel, a federal criminal defense lawyer in private practice, represented Guantánamo detainee David Hicks and is currently an advisor to the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers on the representation of high-value detainees.

Shares