With public attention focused on President Obama’s compromise with Republican leaders to extend the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy, there has been less discussion about a feature of the deal that could have enormous long-term consequences: the payroll tax holiday. Under the plan, which still must be approved by the House and Senate, the payroll tax would be cut by 2 percentage points for all wage-earners — meaning that a worker making $40,000 would receive an extra $800 in his or her paycheck over the course of a year. The White House and its defenders are touting this as a way to boost the stalled economy, and it might just do that. But they’re also playing with fire.

For supporters of the program, the use of Social Security tax reductions for economic stimulus is a dangerous political precedent. The tax holiday plays directly into the “Starve the Beast” strategy that conservatives have pursued since the 1980s. After Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, Republicans learned that directly attacking domestic programs was hard to do. When Reagan pushed for cuts in Social Security in 1981, he faced a massive backlash that forced him to back down. President George W. Bush encountered the same fate in 2005 when he tried to spend his political capital on Social Security reform. The lesson was learned. Republicans instead focused on a strategy whereby ongoing tax cuts would gradually leave the federal government with less revenue for new programs and make existing programs susceptible to attack as a result of deficits.

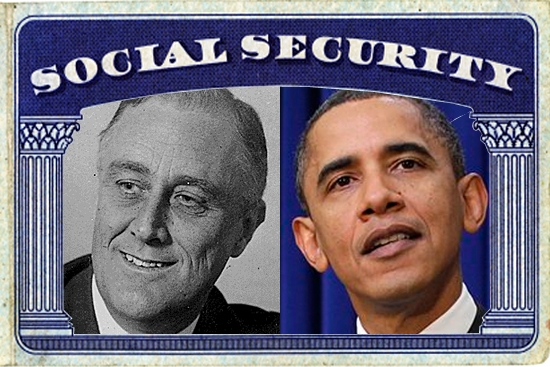

A key reason for the program’s strength has been the sanctity of the Social Security tax, which has been treated as a special tax, distinct from income and corporate taxes, on the grounds that it is linked to a specific government benefit. Every year, Congress uses the funds collected from payroll tax contributions of workers to pay for the benefits of current retirees. “With those damn taxes in there,” Franklin Roosevelt once declared, “no damn politician will ever scrap my Social Security program.”

The Social Security tax served two main political functions. The first has been to create strong ongoing support for the program from those who pay the taxes and those who receive the benefits. Social Security’s contributory tax system creates perceptions of earned rights and helps distinguish the program from welfare. The tax has also made Social Security an inherently conservative program, at least from a fiscal standpoint, which has traditionally allowed many budget hawks — like Wilbur Mills, the old Ways and Means chairman — to support it. Unlike almost any other program, policymakers have been forced to adjust taxes to pay for the short-term obligations of government and to plan for future costs. The contrast with almost any other form of government spending, such as defense and agricultural subsidies, is striking. The design forced Congress to take the unpopular step of raising taxes and cutting benefits in 1977 and 1983 when the system faced insolvency.

Thus, opponents of the program have tried to undercut the payroll tax. From 1935 to 1950, Social Security remained a small and frail program. The program covered only a limited part of the workforce and paled in comparison to Old Age Assistance (a means-tested program for the elderly) that was far more generous. In 1939, Congress abandoned the original plan to build a surplus of revenue to pay for Social Security benefits. During World War II, Congress froze Social Security taxes and in 1944 passed an amendment that authorized the use of general revenue to eventually pay for benefits.

Social Security supporters fought to protect the tax. They realized, as the Social Security Board stated, that the payroll taxes was the “psychological basis” for the program. Social Security supporters warded off the threat when in 1950 Congress passed amendments that prohibited the use of general revenue and ensured that payroll taxes would be the only mechanism through which Social Security benefits were paid for. There have been times when politicians privately thought about this part of the equation. In 1967, for example, LBJ believed that a Social Security tax increase — which was tied to a benefit increase — would help restrain inflation at a time that Congress was refusing to pass a tax surcharge for this purpose. But the White House and Congress were very careful to avoid making this part of public discussions or the explicit reason for any change in the payroll tax rates.

Many liberal economists were never comfortable with this agreement. During the 1970s, as the political scientist Eric Patashnik argued in “Putting Trust in the US Budget,” Keynesian economists challenged the tax structure. They argued that the payroll tax undercut macroeconomic policies. Payroll tax hikes constituted a regressive way to fund benefits and sometimes went into effect when the government was trying to stimulate the economy. There was another strong push to use general revenue. Generally, their efforts failed and the payroll tax remained outside the debates over stimulating or restraining the economy. When Republicans pushed for income and corporate tax cuts after the 1980s, Social Security taxes continued to rise.

By insulating the payroll tax from the perennial debates in Washington over cutting taxes to stimulate demand and investment, politicians have protected the program from short-term economic and partisan pressures.

But this time the situation appears to be different. President Obama and the congressional Republicans agreed to break with this precedent. In the future, proposals to further cut Social Security taxes — including to do so on a permanent basis — will certainly be on the table. Once politicians have tasted the political sweetness of tax cuts, they always come back for more. If they succeed, it will worsen the long-term budgetary challenges facing Social Security and create more room for opponents to attack. Indeed, simply by entering into a bipartisan agreement to change the way that Social Security taxes are discussed, the odds improve that one day, some politician might very well be able to scrap FDR’s program.