The Civil War has not ended. Despite the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox in April 1865, the war and its legacies still provoke political controversy.

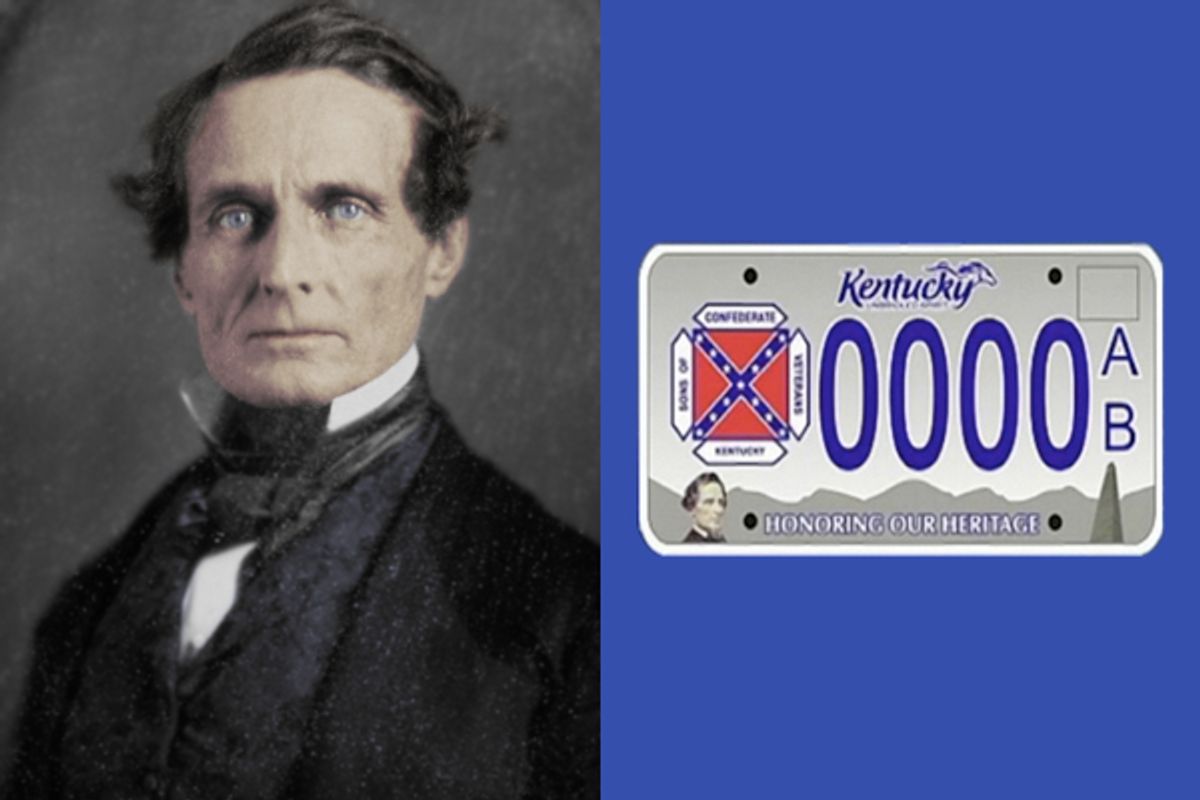

Last week, for example, the Kentucky division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), a fraternal organization composed of descendants of soldiers who fought for the South during the Civil War and that attempts to promote a Southern interpretation of the war, proposed that the state issue vanity license plates bearing the images of the Confederate battle flag and Jefferson Davis, a son of Kentucky who served as the Confederacy’s only president.

The proposal has aroused a storm of protest in the state, particularly by African-Americans and black organizations such as the NAACP. An SCV spokesman, quoted by MSNBC, said that "the idea with the plate is that everything with the SCV is to honor Confederate soldiers, heritage and history, and the SCV and get this in front of the public" (presumably this quote is verbatim). But the Louisville Courier-Journal reported that Raoul Cunningham, president of the Louisville branch of the NAACP, said the Confederate flag "is offensive. It is an emblem that is mostly associated with the Confederacy and slavery. It is offensive to African Americans." Cunningham vowed to launch a legal challenge to the license plate, but the state’s Transportation Cabinet revealed that the SCV has yet to file an application for the plate.

Probably the SCV should not waste its time trying to do so. Although the SCV has successfully persuaded nine former Confederate states (there are 11 such states in all) to issue commemorative license plates, Kentucky will probably resist the group’s effort, even if the SCV does getting around to submitting a formal application.

For one thing, Kentucky never joined the Confederacy, even though it was a slave state. During the Civil War, more Kentuckians served in Union regiments than Confederate ones, despite the deep divisions that made the conflict truly a war of brother against brother in the state. Despite its fondness for slavery as a labor source and as a means for racially controlling blacks, Kentucky remained staunchly Unionist during the war years. Suffering from an acute case of wishful thinking, Confederate authorities added a star to the rebel battle flag (the red flag with the St. Andrew’s cross, which most people incorrectly identify as the Confederate national flag) for Kentucky, but the star did not make Kentuckians give up their loyalty to the Union or persuade them to throw in their lot with the South.

Yet, the SCV campaign for a Confederate license plate might make some headway among some present-day Kentuckians, if only because historians have long argued that the state and its people began to express vigorously pro-Southern and pro-Confederate sympathies ever since Lee's surrender. Kentucky, like so many other states located south of the Mason-Dixon Line or south of the Ohio River (or red states in the Midwest and West), basks today in a warm nostalgia for all things Southern, particularly if those things date from the antebellum period, when presumably white Southerners sat on their verandas drinking mint juleps and listening to contented slaves serenading them.

For anyone paying attention to the running of the Kentucky Derby on May 7, you no doubt noticed that "My Old Kentucky Home" was sung in earnest by the spectators while standing up before the race, as if the song was the national anthem. Actually, the song was written by Stephen Foster (a Pennsylvanian) in 1853, one of hundreds of minstrel tunes that he composed in his lifetime (he was, in some respects, the Irving Berlin of his time). The Kentucky General Assembly made it the state song in 1928.

What most people don’t know, however, is that there are two versions of the song, which tells of a slave who misses his golden days spent on a Kentucky plantation (he seems to have been sold down the river, where slave life was harsher than in the border states). Foster’s original lyrics say "the darkies are gay" (note for modern readers: "gay" means happy, not homosexual) living "where all was delight," although they include some references to toting "the weary load" and other heavy work done by slaves. The lyrics were changed in 1986 by the Kentucky General Assembly after Carl Hines, the only black member, complained that the lyrics "convey connotations of racial discrimination that are not acceptable." Most conspicuously, the word "people" was substituted for "darkies." The song is sung often here in Kentucky, where I teach, and particularly at every graduation ceremony of Western Kentucky University (December and May). I’m told it’s also performed before every football game and after every basketball game at the University of Kentucky, which in this state is called "UK" (as a transplanted Northerner here, I’m still in the habit of thinking that UK stands for the United Kingdom). Occasionally, as one becomes accustomed to hearing "My Old Kentucky Home" wafting o’er various live venues, inevitably someone in the singing multitude will stir things up by purposely singing "darkies" instead of "people." In Kentucky, tradition dies hard.

The same can be said of the South and the SCV, which is hell-bent on making sure that the Confederate flag, which it claims is a symbol of "heritage, not hate," is always visible, if not on flag staffs, then at the very least on license plates. Of course, the national debate over the Confederate battle flag is nothing new, but white Southerners -- who prefer their "history" to adhere to the melancholic tenets of the Lost Cause (on the insidious nature of the "Lost Cause," see the recent Salon essay by historian Joan Waugh) -- seem determined to argue falsely that the flag only honors the courage of the Southern soldiers who fought for the Confederacy; in the South, most whites still erroneously believe, no matter what historians say, that the Cause stood for states’ rights alone and not slavery. Interestingly, it’s not enough for the SCV to promulgate inaccurate history. It also has the audacity to claim that it’s a victim of discrimination. "It’s sort of typical of the way anything Southern or Confederate get treated anymore," the Kentucky SCV spokesman told the Courier-Journal. "It has to go through the political-correctness filters, rather than the historical-correctness filters."

Unfortunately, the SCV’s own "historical-correctness filters" are entirely flawed or perhaps clogged. If the Confederate battle flag had only been used by Southern soldiers during the Civil War, the SCV might be able to make a stronger case that "heritage" is their only interest in displaying the flag so prominently throughout the South. Still, African-Americans probably would dislike the flag, given the fact that it stands as a symbol for a nation -- the Confederate States of America -- that sought to protect, defend and prolong the institution of slavery. In his famous "Cornerstone Speech" of March 1861, the Confederate vice president, Alexander Stephens, declared that the new nation’s "foundations are laid ... upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition." White Southerners, like the members of the SCV, may wish that the battle flag could be just a symbol of Confederate bravery, but the flag itself -- in 1861, when it was first designed, and today -- is actually a symbol of exclusion and racism, meant 150 years ago to be for whites only, even if modern members of the SCV do not think of it in those terms.

But the larger problem with the battle flag is that it was used purposely during the 20th century and in our own time as a symbol of hate -- a direct contradiction to anything the SCV claims. After the Civil War, the United Daughters of the Confederacy adopted the flag in its effort to rewrite history according to the gospel of the Lost Cause. During the 1930s, the Ku Klux Klan, a terrorist organization that was revived in the 1920s, used the flag as a rallying emblem of white supremacy. From the 1950s to the 1960s, as historian John M. Coski has expertly demonstrated in his superb book, "The Confederate Battle Flag" (2005), the flag became "not simply a symbol of perceived racism in the country’s distant past but a symbol of explicit racism in the recent past and present."

After the rise of the Dixiecrat party in the late 1940s, the flag could be found prominently waving across the South -- even more frequently and in more places in the 1950s and 1960s as the civil rights movement gained headway than it had ever been flown during the short lifespan of the Confederate States of America. In 1952, an African-American newspaper in Baltimore saw clearly that the flag had become a symbol for "slavery ... rebellion ... bloodshed and segregation ... oppression and disfranchisement ... [and] white supremacy."

One can argue, as the SCV does vociferously, that blacks are wrong in seeing the flag in this light. But the SCV's own protests that the flag represents "heritage, not hate" are overwrought once one understands that black Americans have every right to regard it as a pernicious emblem. It also bewilders me why the SCV goes to such extremes to insult African-Americans in its campaign to champion the flag. Why would respecting the wishes of blacks today by taking their feelings into account detract from the heroism of the SCV’s Confederate ancestors? Putting the Confederate flag on a license plate doesn’t honor Confederate valor, it diminishes it. A license plate? Around here most license plates are covered in mud, especially given the plentiful spring rains we’ve had in Kentucky this year.

My point is that the Confederate battle flag is nothing a white Southerner should be proud of. It’s an embarrassment -- or at least it should be to anyone who truly believes in freedom, who understands that the Civil War ended slavery forever in this country, and who respects that millions of Americans, many of whom are descended from slaves, resent and despise a flag that stands for white men who willingly gave their lives 150 years ago so that slavery could be perpetuated, or, for white people who sought with all their might to prevent African-Americans from enjoying the rights and freedoms guaranteed to everyone else. Either way, in my opinion, the Confederate battle flag remains an icon of hate, not heritage. It belongs in museums, where it should freely be displayed. If it is placed on a license plate, it deserves to be splattered with mud.

Saying that, however, will not endear me to my Kentucky neighbors or my students, most of whom -- despite my efforts to convince them otherwise -- seem to believe that the Confederate battle flag flew proudly over this commonwealth from 1861 to 1865 and should be displayed more prolifically now that we have entered the Civil War’s sesquicentennial. Nevertheless, the flag -- no matter what the SCV thinks -- continues to be contentious here, as it does throughout the country. As Tony Horwitz reported so movingly in the Wall Street Journal and later in his highly acclaimed book, "Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches From the Unfinished Civil War" (1998), white Southerners are still dying for the Confederate battle flag. Horwitz vividly describes how, in January 1995, 19-year-old Michael Westerman was pursued from Guthrie, Ky., to Robertson County, Tenn., by three carloads of black teenagers. The chase ended with an African-American shooting and killing Westerman. The black teens maintained that Westerman had shouted racial epithets at them, but some people believed that Westerman was killed because he flew a large Confederate battle flag from a staff attached to the cab of his truck. The case was complicated, not only by a flawed investigation and conflicting testimony, but also by the intense racial passions that Westerman’s murder aroused in Guthrie, in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, and across the nation. The victim was lionized as a Confederate martyr, the Klan moved in to spread its propaganda, and the community was torn apart. Two of the black teens were found guilty of felony murder, intimidation and attempted kidnapping; they are both serving life sentences. The mayor of Guthrie told Horwitz: "When I was a boy, no one cared about that flag. Heck, I never even thought of myself as Southern. But today there’s this intolerance, white and black. People feel they have to wave their beliefs in each other’s faces."

Not much has changed since 1995. Heck, in some parts of Kentucky not much has changed since 1865, when white Kentuckians, who detested having to give up their slaves when the Civil War ended, decided they would henceforth side with the dead Confederacy rather than with the victorious Union. Kentucky did not ratify the 13th Amendment until 1976. Meanwhile, the sun shines bright on my old Kentucky home. I hope in the near future that it never gets to shine on a Confederate battle flag emblazoned on this state’s license plates.

Even so, the battle flag will not go away, no matter how divisive it continues to be. All I have to do here in the land of thoroughbreds and fried chicken is check my rearview mirror on the interstate. Inevitably what I see is an 18-wheeler bearing down on me with a Confederate battle flag stretched across its radiator. In a split second, every frame of Stephen Spielberg’s first movie, "The Duel," flashes through my brain. Maybe it’s time for me to remove the "Obama ’08" bumper sticker from the back hatch of my Jeep.

Shares