Al Pacino was once asked in a Playboy interview what actress he’d most like to work with. His answer: “Julie Christie, because she’s the most poetic actress.”

“Poetic” is the best possible word to describe Julie Christie. If every great actor embodies an essential paradox, Christie’s is that she’s both tigress-direct and fawn-subtle, often at the same time — the cross section of haiku and a sonnet. You find yourself watching in wonder to unravel the quiet but sometimes ferocious mystery of her performances, from her shallow social climber in John Schlesinger’s 1965 “Darling” to her shrewd but ferally tender madam in Robert Altman‘s 1971 “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” to her fragile Gertrude in Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 “Hamlet.” Many of her characters are, on the surface, crisp, forthright, almost businesslike, but there’s always a soft layer of vulnerability beneath her fine-boned beauty. She’s naked even when fully clothed.

Christie was born in India in 1941, where her father ran a tea plantation. She went to school in England and Europe, eventually enrolling in the Central School of Music and Drama in London in 1957. As a young professional actress, she did stage work and had a regular role in a British TV series, “A for Andromeda,” in the early ’60s. In 1963 she appeared in Schlesinger’s drab working-class comedy-drama “Billy Liar,” and although it wasn’t her film debut, she grabbed the attention of movie audiences and critics.

The story of a young man, played by Tom Courtenay, who retreats into a fantasy world to escape his unglamorous life, “Billy Liar” is leaden and vaguely smug; we’re made to feel beaten down by the monotony of Courtenay’s life, so that by the movie’s disheartening conclusion, we’re well primed for self-congratulation: “You see, we knew nothing would work out right in the end.”

But Christie, as the vibrant young woman who represents the last shred of real-life hope for Courtenay, brightens the movie whenever she appears. Her character has no depth or resonance, but she’s pure light. As the sunny, fearless girl who appears seemingly out of nowhere to tempt Courtenay to freedom and fun — freedom and fun that he has difficulty allowing himself, at least in real life — she’s like a vision of everything the ’60s were, at their best, to become. It’s supposed to be tragic that Courtenay can’t partake of them, or of her. But when he and Christie part at the movie’s end, you barely feel sorry for him. Her smile, dazzling at the age of 22, scotches the final effect of the movie: We’re left thinking, How could the boy be such a schmuck to let her go?

Christie was flying high by 1965, appearing in two major films: Schlesinger’s “Darling” (for which she would win an Academy Award) and David Lean’s “Doctor Zhivago,” in which she played Lara, the tragic heroine.

But “tragic heroine” isn’t quite the right phrase for what Christie does in that picture. The term implies histrionics, or at least some sort of submerged melodrama. Christie carries the core of the movie’s sorrow — and that means the sorrow of revolutionary Russia, as well as her own — not just in her hopelessly blue eyes, but in the set of her jaw. She’s stalwart, brave, reliable beyond compare, and still, she suffers. What Christie doesn’t do is turn the performance into an exercise in masochism. Before she even played one, she proved she had the heart and soul of a Thomas Hardy heroine — a woman who was made to bear sadness but retain her inner dignity at all costs.

But before Christie would tackle Hardy, she put an entirely different sort of woman on the screen: shallow, clever, earth-quakingly gorgeous and determined to be a star regardless of the emotional cost to herself and those around her. In “Darling” Christie played Diana Scott, a fashion model who hooks up with a brainy TV journalist (Dirk Bogarde) only to end up ditching him for a cold, dashing figure who can introduce her to more of the “right” people (Laurence Harvey).

The story is supposed to be a morality tale, a snapshot of swinging ’60s greed and corruption, but Schlesinger layers on so much heavy-handed irony that it’s really more of a cartoon. I’m not sure what the movie looked like to audiences in 1965, but in 2001, it’s all too easy to watch it and decree with a shiver that, yes, those ’60s people were all too dreadful. There’s something more than vaguely distasteful about the way “Darling” cooingly reassures us it’s better to be conventional, “normal,” because you’re more likely to end up a moral human being that way. It’s numbingly facile — no deeper than an air kiss.

The thing that’s amazing about “Darling” is the way Christie takes a chalky caricature and turns her into a human being. She unintentionally undermines the movie: While you’re supposed to be tsk-tsking over her behavior, you see that the same gears that drive her manipulativeness also throw off blazingly intelligent sparks. Christie swaddles Diana’s matchstick frailty in heartlessness, but she knows it’s a transparent cloak. As Pete Townshend sang not long after, in a song that had nothing to do with Christie but everything to do with the hypocrisy that “Darling” tried so hard to expose, “I can see right through your plastic mac.” In “Darling,” Christie, the most honest of actresses, doesn’t even bother to do up the buttons.

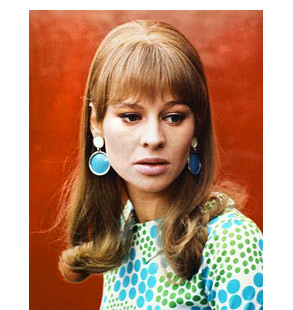

When “Darling” became a hit, both in the U.K. and stateside, Christie, even more so than most movie stars, began to represent more than just the parts she chose and the way she played them. She represented the spirit and style of her era, but not in a way that was forgotten in a month or two. Even today, Christie still stands as the actress of the ’60s, the way Clara Bow was the “It” girl of the ’20s. It had not only to do with her talent, nor even with the fact that she was English. (To be English in the ’60s was coolness itself.) She seemed to speak a language of her own, a language her contemporaries instantly understood, in the way she carried herself and the way she dressed. “What Julie Christie wears has more real impact on fashion than all the clothes of the ten Best-Dressed women combined,” Time magazine decreed in 1967, and for once, Time was right. Captured in fashion photos from the era, Christie paints even the most ridiculous clothes with dignity. In pictures from the late ’60s, she’s the model of droopy elegance in haute-hippie garb. Just a few years earlier, in a mid-’60s fashion shot by David Bailey, we’d seen her looking serious and gorgeous in a dress of shimmery paillettes, their silliness offsetting her sun-kissed gravity.

From the mid-’60s to the mid-’70s, Christie was a major presence in popular movies. In 1967 she played that Hardy heroine for real in Schlesinger’s “Far From the Madding Crowd,” a picture that captured the bleak beauty of Hardy perfectly. As Bathsheba Everdene, a plucky, self-sufficient landowner who becomes enmeshed in the love of three different men, Christie again balances that graciously composed façade with an innocence that’s buried deep; she shows a kind of cautious openness to the world around her. What makes her Bathsheba so moving is that no matter how many trials she faces, she never seems to be on the verge of cracking. Instead, she lets you see, with little more than the flicker of an eyelid or a reserved smile, how painful it is to persevere, and to bend. An extraordinary cast joined Christie, including Terence Stamp and Alan Bates, but the movie was rejected by the same audiences that loved the supposedly with-it quality of “Darling.” “Far From the Madding Crowd” is a picture that has never quite received its due; it ranks among Schlesinger’s best work, as well as Christie’s.

Christie racked up an astonishing number of movie credits through the late ’70s, among them François Truffaut’s “Fahrenheit 451” (1966), Richard Lester‘s “Petulia” (1968), Nicolas Roeg’s “Don’t Look Now” (1973) and Warren Beatty and Buck Henry’s “Heaven Can Wait” (1978). She has worked fairly steadily since then, although she hasn’t always been in the spotlight. Notoriously guarded about her private life, she’s the kind of actress who resurfaces now and then in a terrific performance, and you ask yourself where on earth she’s been. In 1997 she appeared opposite Nick Nolte in Alan Rudolph’s “Afterglow,” for which she earned an Academy Award nomination. In 1996, she played an aging but still incontrovertibly sensual Gertrude in Branagh’s “Hamlet”; it was one of the most remarkable performances of her career.

But my two favorite Christie performances, four years apart, seem like spiritual counterparts to each other. They also, as it happens, feature the same costar, Warren Beatty, with whom Christie was romantically involved in the early ’70s.

It seemed that once Beatty and Christie — who reteamed for a third time in 1978’s “Heaven Can Wait” — locked in to each other’s natural rhythms, as lovers do, there was no turning back. They’re one of the most natural, effortless movie pairings ever. In both Altman’s “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” and Hal Ashby’s 1975 “Shampoo,” Christie is the tougher one, the woman who faces up to everything that her male partner just can’t. In “McCabe,” she’s Constance Miller, a brothel madam who sweeps into Presbyterian Church, the frontier town run by John McCabe (Beatty), ready to get down to business. There’s something lustful, but not sensual, about the way she sits down at the town cafe and orders up “four eggs fried, stew and strong tea.” It’s the equivalent of a Wild West power lunch. She eats it like a man or, more specifically, like a convict, shoveling the chow into her gob with one hand as she hunches protectively over the plate. McCabe watches, enchanted and a little abashed. He has fallen in love.

On the other hand, the only time Mrs. Miller succumbs to sensuality is when she sets herself adrift on opium: Her eyes soften, and their gaze reaches out as if to embrace an imaginary lover. She’s much less yielding with the shambling, stuttering, heartbreakingly decent McCabe, who becomes her lover. He pays for the privilege, of course. She wouldn’t have it any other way.

Mrs. Miller wears the pants in this tale, and disguised as a sweeping skirt, they’re that much more threatening. Her jaw line — that superb jaw line — is like a ship’s anchor; her hair is aquiver with tiny ringlets, as if hooked up to their own private energy source. She’s the kind of woman even a tough man would steer clear of, which is what makes her moments of tenderness with McCabe so lovely.

At one point McCabe comes to her quarters, distraught and trying to hide it, muttering something about how he’s never been so close to a woman before. You can practically see Mrs. Miller’s own guarded vulnerability welling up inside her, and she’s less able to bear that than she is McCabe’s weakness. Her eyes soften just barely as she cajoles him into bed: “Hey — why don’t you just get under the covers, huh?”

Mrs. Miller knows McCabe better than he knows himself, but she knows herself best of all. That’s why the film’s final image is so haunting, and so troubling: After McCabe’s death, we see Miller propped up and floating into an opium dream, a slight smile playing across her lips. She doesn’t know he’s dead, but their separation is final nonetheless. He’s gone, and he’s taken her with him, figuratively speaking; she’s never coming back. It’s as if her heart, brittle by nature, has broken into two clean pieces, cracked at the hinge like a busted locket. She’s as surprised as anybody that it could have happened.

Christie’s character in “Shampoo,” high-class gold digger Jackie, is in many ways softer than Mrs. Miller. Mrs. Miller has worked so hard at cultivating a tough shell that she’s forgotten how to be tender; Jackie yearns to be soft toward the man she loves, Beatty’s philandering hairdresser George, her ex-boyfriend, but her sense of self-preservation demands that she harden herself toward him.

Christie’s performance in “Shampoo” is one of the most mournfully luminous things ever put on film. Her vulnerability courses through the movie like a barely audible heartbeat, even when, or especially when, she’s trying to treat George indifferently. Her beauty is so cool in “Shampoo” — her hair is a subtle ash blond sweep (no garish Tiffany-gold tresses for her), and there are times when her lips curl into a crocodile smile that’s almost predatory.

But when she and George fall into a discussion of his restless habits, and he tells her bluntly, “I don’t fuck anybody for money, I do it for fun,” you have to watch Christie’s face carefully for the crestfallen look that flickers across it. Suddenly, it’s gone, replaced by her usual crisp composure.

Christie is the sort of actress who reveals more of herself in what she hides than she does in any broad gesture or expression. In one of her most remarkable moments in “Shampoo,” we don’t even see her face. But we can read it even so. She and George, inching toward a reconciliation, find themselves alone in a darkened bathhouse at a swinging party. He has confessed to her, in words that we desperately want to believe, that she’s the only one he loves, that he can’t imagine growing old with anyone else. We see her drinking the words in cautiously, as if she doesn’t dare let herself believe them.

Not long after, just as she and George have begun making love, his current girlfriend walks in on them. George leaps up to run after her, leaving Jackie behind in the dark.

She isn’t, of course, in total darkness. She sits up, and we see her from behind, a naked back that’s less like a body part than a lithe sliver of light. But it’s a piece of light we can read like a book, a sensual curve in the darkness. With her back to the world, Christie betrays a wealth of feeling that we perhaps couldn’t bear to look at in her face. The curve of her spine speaks of resignation, and one last, major disappointment in love. You could call it artful composition on the cameraman’s part, and without a doubt that contributes to the effect. But Christie, like all great actors, understands the truth that bodies tell. There’s inexplicable sadness in the curve of her back, and flexibility, too. But for that moment, she’s simply the woman who’s been left behind. Her back is a rune that spells goodbye.