Rich white men -- corporate titans, leaders of industry, politicians, celebrities -- get fairly leveled in Harry Shearer's newest film, "Teddy Bears' Picnic." The movie spoofs the annual power orgy that is Bohemian Grove, the exclusive, all-male retreat in the woods north of the San Francisco Bay Area. From Enron's collapse to the unfolding tragedy of Global Crossing, there couldn't be a better time for this movie.

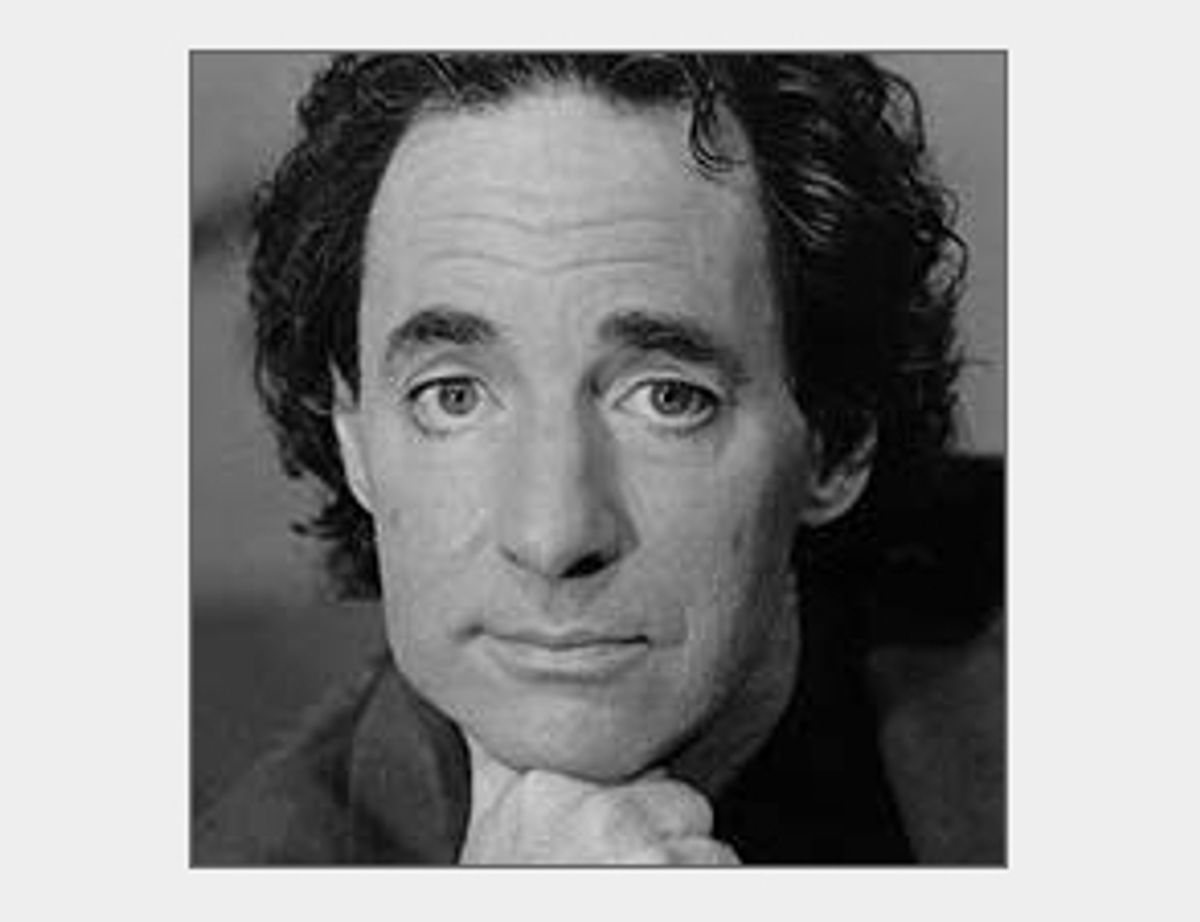

Perhaps most memorable as heavy metal bassist Derek Smalls in the 1984 mockumentary classic "This Is Spinal Tap," the actor, comedian and satirist is also no slouch when it comes to more serious cultural criticism. There's his weekly radio program, "Le Show," writings for the online magazine Slate, commentary for programs like "Now with Bill Moyers" -- public television's sleeper hit of the season -- and even a brief column in Salon. And Shearer's list of film and TV credits is endless.

His take on power and corruption is a nuanced one. To Shearer, what's most compelling about the Enrons of the world is that their corruption is largely circumstantial; give anyone that kind of wealth and the results won't be pretty. From the rich down to the poor, we're a partially defective species. "That's what's funny," Shearer explains. "We wouldn't be able to laugh at Shakespearean comedy today if we weren't the same flawed people that we've been for a long time."

"Teddy Bears' Picnic," which Shearer wrote, directed and executive produced, opens Friday in limited release. He recently spoke with Salon about his film, Jimmy Swaggart, Starbucks, Linda Tripp and the general state of the world.

Your film is about a bunch of white men and the havoc they can wreak. It seems pretty timely, given the state of thing like Enron, K-Mart and Global Crossing. Did you see this all coming?

It's not so much that I saw it coming, but that I see it being. It doesn't change really. There was a period last fall when I would watch the movie at film festivals where I thought, maybe people aren't ready to see this view of those in power yet. But thankfully that moment has passed. This was conceived some time ago, when it was a different group of people who were messing around like this. It seems like there are always going to be these folks. The show goes on.

It's all about flouting the rules. Doesn't it seem like everybody lives by that today?

Not everybody. The iron law is when there's this much money at stake people are going to be fairly crudely rational creatures and, rules be damned!

Then who does live within the rules?

Most people who don't have access to power and large amounts of money. Those are the two goads to cheat. I thought, when I first started seeing high-money show business, that it was a sort of iron law that the more money on the table, the worse the behavior. I haven't been around that much power but I think people, when faced with huge, insane amounts of money and seductive amounts of power, are weak creatures. And the rest of us who aren't so tempted find it easier to say, "Oh, no parking here at 9, OK. I'll move my car."

Are we just suckers then?

We're just the same people put in different circumstances. That's the difference between conventional satire, which says, "ooh, the powerful are bad people," and what I think is a more comedic view, which is, if you or I were faced with these temptations and these seductions, we might act just as badly as these folks do.

What would you say to the point that some people make, that the state of our union has never been stronger?

I think the difference between a better time and this one -- and it's strong in my mind because I'm a part-time resident of a place where it isn't true -- can be found in the relative weakness of community at this point in time. The individualist ethic has so triumphed over the community ethic. They should exist in some sort of balance but nothing exists in a balance in American society. Either it's too much of one thing or too much of another. So we right now have way too much emphasis on "I got mine," and way too little emphasis on things that bind communities together.

As I say, I live part-time in New Orleans where there is so much more spirit of community that it puts what goes on in the rest of America kind of in dramatic relief. People aren't different but the circumstances that they are in as living arrangements tend to either push them toward more of that or less of that.

You see a yearning to get more of that again in these Main Street-style malls that are being built, which are trying to summon the semblance or a simulacrum of community without actually the essence of it. So there's clearly a feeling that we need more of this but we don't know how to get it at this point. "Let's all read the same book" is as close as we can come.

And wear the same clothes, and drink the same coffee. Yet you've bemoaned the lack of a Starbucks in an airport when you're stuck there for an hour and a half waiting for your luggage.

I sure do. Because Starbucks is not the problem. The problem is the fact that the only place in town where people sit for any length of time and maybe talk to each other is Starbucks. That's the problem. The problem is that Starbucks filled a hole -- Starbucks didn't invent that hole. There might not be so many Starbucks if there were more plazas, if there were places that older cities discovered were good ideas for people to hang out, where they don't have to spend $3 to get in.

Let's go to Enron. What if Enron had never existed?

It's this weird cycle. It's hard to remember back to the beginning of the '90s, oddly enough, when everybody was sort of shaking themselves like wet dogs after the go-go cycle of the '80s. The materialist, greed-is-good, Michael Milken-fueled '80s saying, "Whew, we're not going to do that again." Then within three years, we did it all again, so much bigger and so much grander, at the loss of so much more money to so many more people.

It just makes you kind of tremble at the thought of what lies ahead for us two years from now, when we've kind of shaken this off and gone, "Whew, we're not going to do that again." I think the four least believable words in American public life are, "once and for all." When you hear a politician say, "once and for all," you know he's lying. It's going to happen again.

So our problem is a short memory?

Well, that is the American gift, you know -- to have a short memory. Hence, Jimmy Swaggart can make a comeback. Anybody can make a comeback, anybody can make three comebacks in this country. Why I like California is because this is the personal reinvention capital of the world. It's got the shortest memory span because it's got the least things to remember.

Any shocking comebacks?

Start with Ted Kennedy, that's a favorite of the conservatives. Jimmy Swaggart, who is now a fairly successful gospel singer. Jim Bakker gets out of jail and goes right back to a ministry. The guys who don't do well in this country are the guys who don't figure out that you just have to fall on your knees and go, "I am so sorry." And then you get to do whatever you want after that.

That's sort of the formula. It's why, for example, the Protestant clergy who misbehave get it, because this is a formula that sort of comes out of the Protestant experience, whereas the Catholic pedophile priests don't get it and end up being protected for years and then reviled. But they never realize, that -- well, pedophilia is not something you can apologize for anyway. Whole different category of event. We'll drop that ...

Let's get back to politics. How about Dick Cheney having to hand over documents about his energy task force and policies? A step in the right direction?

If you live long enough, one of the rewards is to get the privilege of seeing each political cliché mouthed in turn by partisans from each side. So that the same people who were desperately demanding that we know chapter and verse about Hillary Clinton's top-secret healthcare task force are now saying, "No, no, no, confidentiality, it's an important principle." And vice versa.

It explains why, or it's a consequence of the fact that most of our politicians are trained as lawyers. Because that's exactly what lawyers are trained to do: Take this side, all right, now take this side. That's what they do. And anybody who thinks that they're doing anything else is welcome to bid for some Enron stock certificates on eBay, because that is the game.

Who do you look to for moral leadership?

My own conscience.

Maybe you were brought up right. What about the rest of us?

Well, I was brought up by wolves. Never trust that.

"Teddy Bears' Picnic" offers a bleak picture of things. These powerful white men who make a mess of everything -- they're not going anywhere, right? They'll have their clubs and groups and continue to make a mess of companies and people's lives.

One of the things I find so unsatisfying about an awful lot of Hollywood formula comedies is that they do feel the need to be hopeful. People learn stuff and people change and people get better and they learn to hear each other and talk to each other and understand one another. I don't know what's funny about that. I know what's funny about that as a premise, which is that it's ludicrous. I don't know what's funny about the resulting work.

To me what's funny is how flawed we are, that's what's funny. And you know, we wouldn't be able to laugh at Shakespearean comedy today if we weren't the same flawed people that we've been for a long time. Shakespeare was drawing on a lot of the same stuff as the comedies of ancient Greece. It's hard to resist the idea that we're the same flawed people that we've always been. So to sell fake hope about us changing is the funniest thing of all.

Why do we expect that we shouldn't be flawed? And isn't there any hope?

There's hope and there's dismay in equal measure. It's not a totally dark view of the world. One of the things I was trying to do -- I feel a little presumptuous at even mentioning my little film in the same context -- but I always admired Billy Wilder's ability to create stories that felt like [they had] happy endings until you thought about them, and then they weren't, really.

What New York went through, it has this in equal measure. You're surprised by the ability of people to just pitch in and help in difficult times, and then you're surprised or dismayed by the ability of people to wrangle about, "well, they're getting more money than we are," immediately afterwards. And both things are true. It's an imperfect view of the species to insist that we're only one or the other.

But isn't it distressing that not even something of the magnitude of Sept. 11 would make us stick with the good and not veer to the bad?

I think it's amazing that in the face of something so bad the good immediately is the first thing to come out. It takes people about a week to figure out, let's make T-shirts out of this.

Back to this question, again: How much of us being this way is the effect of those powerful, rich people?

I don't think it's "poor pitiful us." As I say, I do think the comedic view of this is that if we were subject to their temptations and their seductions most of us would act exactly the way they do. They're us and we're them. That's what makes it comedy and not stick figure satire in my mind -- it's not "They're evil and we're good and we're corrupted by them." They're us in different circumstances. Like Linda Tripp said: "I'm you!"

Are there people out there who've impressed you with their ability to avoid that temptation?

The people that inspire me more often than not are artists who keep on plugging away despite the lack of great commercial success. I take great strength from the fact that, Jesus, if they can keep going, what the hell do I have to complain about? That functions more as a beacon for me than a guy who runs a company. That's so much more of a foreign environment to me. It doesn't relate as much to what I have to do every day, so it doesn't have exemplary power for me.

The one place where I feel some degree of resonance with them is directing. When all is said and done and you've had all the great ideas, directing is an exercise in management. So people who have interesting ideas about managing people, I relate to that because I think a lot about the task of managing people on a movie set. You have to get a bunch of different people with different crafts and different ways of looking at the world and basically who speak different languages -- all of them stemming from English -- to kind of do what you want them to do most of the time, and also to share with you their questions and their thoughts in a reasonable way. That's a management task. That's about the most I can empathize with the corporate guys.

In movies, too, there are directors who feel that it's important to hold information close and there are directors who feel that it's important to distribute information widely. And I think that's sort of the template for good and bad managers in corporations. You know, people who jealously guard information and keep little fiefdoms, as opposed to people who believe that, you know ... George W. Bush keeps preaching the idea when he goes abroad, that "we love transparency." But it's more in the preaching than in the doing among his circle, I fear. Bob Dole used to bellow, "Where's the outrage?" and I used to bellow, "Where's the transparency?"

Were you a transparent director?

I tried to be. Some things are personal. I tried to tell everybody what was going on as much as possible. And to hear their feedback. I can only run things measured by the way I'd like them run if I were a cog in the machine. I think that whatever people think of the film, most of the people who worked on the film had a nice experience. That's not the ultimate measure, but it's something you'd like people to do. Especially with comedy. I've never understood people having a bad time making comedy. Why would you do that? One of the prerequisites to making people laugh, it seems to me, is kind of being in an easy, jocular mood yourself.

Shares