Akari wears a pleated navy miniskirt and a white sailor middy, standard issue of junior high schools all across Japan. But the skirt is minuscule, and her middy hangs down below its hem. Akari's brown, gently bowed legs are bare on this icy January night save for the "rusu-sokusu" (loose socks) gathered in folds at her skinny ankles. She wobbles a bit on her eight-inch platform boots. Completing the look (modeled on the anime character "Sailor Moon," from the eponymous series about a clumsy, lazy and tear-prone 14-year-old who transforms herself, through magic, jewelry and makeup, into a cute, sailor-suited, love-and-justice-defending crime-fighter) is her hair, which is dyed a brassy gold to offset the burnished walnut tan of her round young face. Dolled up in her tiny uniform (purchased secondhand for about $100 from a friend who outgrew the skirt long ago), a sucker lolling from her pink mouth, Akari is one of Japan's many "kogaru," "ko" from the Chinese character for "little," and "garu" coming from the English word "gal."

Haruna, who is standing arm-in-arm with Akari on the street corner, wrinkles her nose at her friend's schoolgirl-sexy getup. She favors instead what she calls a "darker image." In her tremendous silver wig, brittle as an electrocuted bird's nest; her glittery false eyelashes that sweep down past her cheekbones when she blinks; and her mangy fleece jacket worn over Day-Glo orange hot pants and "sockboots" (tall beige socks extending down over foot-high rubber soles), Haruna looks like a pretty drag queen in the tradition of RuPaul. Her skin is a patchy ochre. To achieve this hue, she admits to paying regular and pricey visits to a Kanazawa franchise of the national tanning salon "Blacky." Some label her look the "ike ike onna," the go-go girl. Most call it "ganguro," which translates literally as blackface.

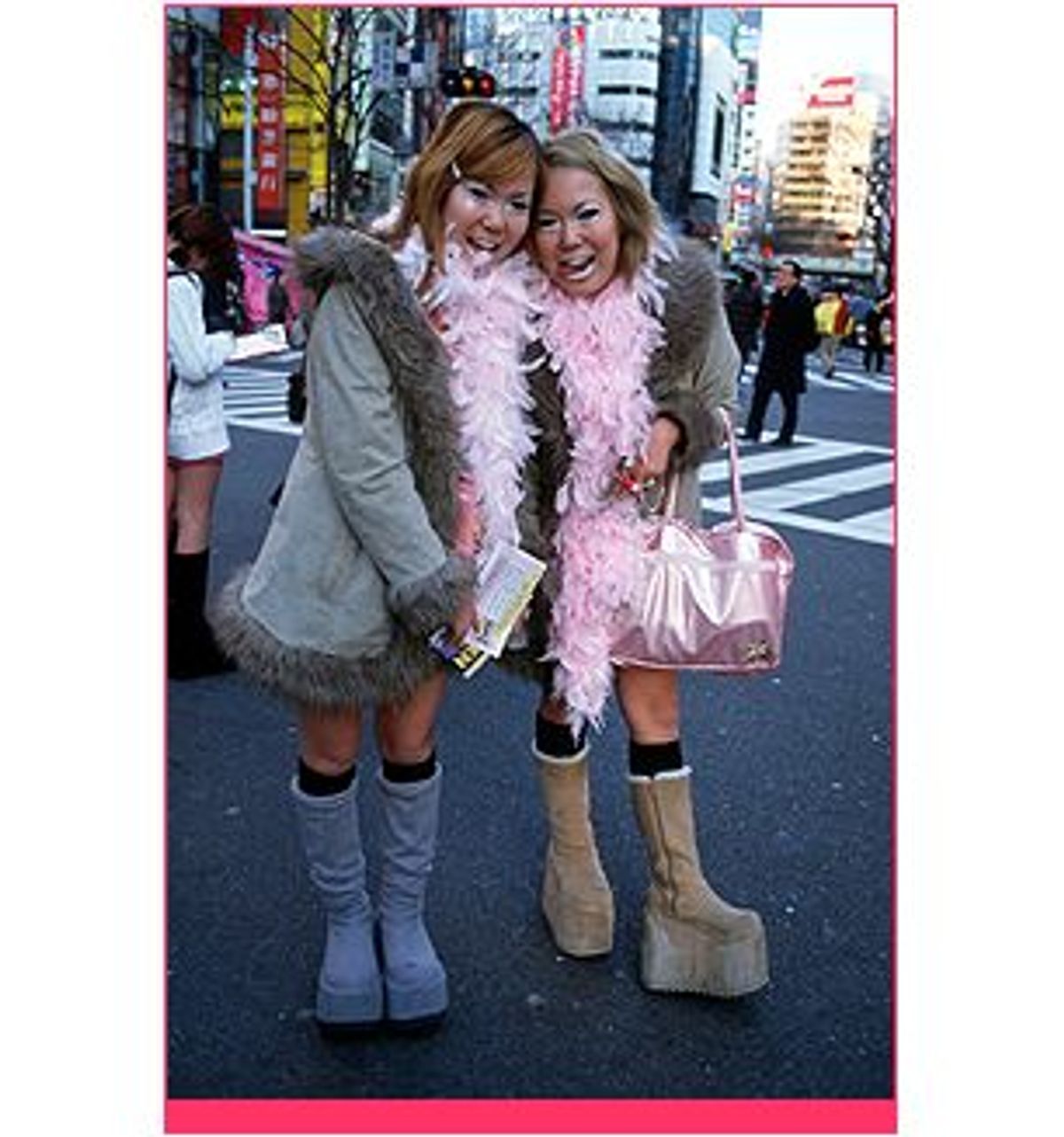

Lately, everyone in Japan seems to be talking about the growing number of kogaru and ganguro girls. In their huge shoes and tiny clothes, faces pierced, hair bleached and teased, they are as easy to spot and as easy to dismiss as those Americans who, in the '80s, forced their bangs, by spray and perm and will, into crispy arcs towering above their faces. An outsider, particularly a foreigner, might mistake a kogaru for a ganguro. But despite their shared predilection for platform soles and body piercings, the two subcultures have completely different fashion aspirations.

Kogaru want to look young, the younger the better. They wear their school uniforms out around town, on dates, probably even to bed. They wear their uniforms but they mess with them, rolling their waistbands so high that their creamy Polo sweaters hang down below their skirt hems, violating school hair and sock codes.

Ganguro want to look black and American, like their idols TLC and Lauryn Hill. In pursuit of a color that's beyond tan, they frequent tanning salons, purchase sunlamps and smother their faces in brown makeup. It's not uncommon for a girl of limited means to color her entire face with a brown magic marker. For those ganguro with the funds, however, Japan's hippest hair stylists will coerce usually rail-straight Japanese locks into bulbous "afuro" (afro) perms that take half a day to set and cost about $400. Whereas kogaru dress like sexy little girls, many Japanese believe that ganguro are prematurely aged by sunning and excessive makeup. Another name for ganguro is "yamanba," mountain grandmother, the name given to a mythical hag said to haunt the Japanese mountains.

Kanazawa is no Tokyo, no fashion hub of the world or even of Japan. Styles take a while to catch on here in the northern province, a famously subdued, bourgeois city of 400,000. Kanazawa is about as likely to set image trends as Providence, R.I. But Haruna's ganguro look is catching on fast, and not just with hostesses, either. While most Japanese employers are reluctant to hire orange-faced women with platinum dreadlocks, growing numbers of "OLs" (office ladies), shop workers, cashiers and even young, stay-at-home mothers are playing the weekend ganguro, putting on tall boots and vibrant wigs for a night on the town. Weekend ganguro can be seen pushing baby strollers down busy sidewalks every sunny Sunday.

In 1999, while the Japanese economy lagged, two new boutiques -- Glamour Jean and Key West -- opened on Kanazawa's main shopping drag, catering exclusively to ganguro. Egg magazine and other glossies aimed exclusively at ganguro are frequently sold out at convenience stores. Signs posted outside hair salons advertise the newly popular "buraku" (black) or afuro hairstyles. And in the cosmetics aisles of mainstream supermarkets, dark beige powders and tanning lotions are now sold alongside the formerly ubiquitous skin-whitening creams and industrial-strength sunscreens.

But despite their growing ranks, both kogaru and ganguro encounter hostility here. In a recent interview published in Kansai Time Out, Japan's eminent novelist Haruki Murakami called them a big problem for Japan, and said that he feels sadness and disgust when he passes these bleached and flamboyantly outfitted young ladies on the streets of his neighborhood, Shinjuku, in Tokyo.

Some of the general prejudice against ganguro style has even become legislative. In Osaka, as of February, it is officially against the law for women to drive wearing tall boots. Apparently they just can't brake fast enough with the platform soles. One woman got in an accident and blamed her platform soles, so a battery of crash tests were conducted with drivers wearing differing sole heights. A maximum allowable platform of only a few centimeters for anyone driving a vehicle was determined.

But if ever there were girls who just wanna have fun, it's these kogaru and ganguro. So why is everyone making such a big deal out of these particular fashion victims?

Here in Japan -- the child pornography export capital of the world -- childishness and sexiness are inextricably bound. So, while it may not be difficult to grasp the kind of naughty appeal that Akari has to men suffering from a "rori-kon," or "Lolita complex," it's not as easy to understand the broader, more pervasive appeal of her childish-but-sexy look.

Even Japanese adolescents seem to equate the two. Just last week, a trio of eighth-grade girls in my English class flipped through an issue of Teen People magazine I'd brought to school for use in a culture lesson. Peering at pictures of teenage stars, my students were unwilling to believe that girls as "mature" and "grown-up looking" as Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera could possibly be under 20. They were particularly shocked by their "mature" clothing and "adult" hairstyles -- no pigtails in sight.

"Kawaikunai," one of the girls said, pointing to a glamour shot of Mena Suvari: not cute.

While the Japanese term "romansuguray" ("romance gray") is commonly used in reference to sexy members of the male salt-and-pepper set, there is no equivalent word for desirable older women. On her 25th birthday, an unmarried Japanese woman automatically becomes what's laughingly referred to as "spoiled sponge cake," in honor of the Christmas sponge cakes that are discounted and rarely purchased after Dec. 25.

This, perhaps, is one of the reasons why Akari is not entirely anomalous here.

She may be wearing the national lower-school uniform, but the 19-year-old is well past her student days. She works as a hostess at the Lullaby Girls Pub in Kanazawa. In the evenings, before the night show begins, she stands with her "masuta" (hostess bar manager, or pimp, from the English word "master") on a bustling street corner and hands out flyers depicting a young, uniformed schoolgirl sitting sprawled like a toddler on a linoleum floor, fingers teasingly splayed over her bare crotch. The photo is framed by a keyhole. According to the flyer, "Guests can enjoy peeking through a real high school student's keyhole without fear of arrest!"

Men who find kogaru hostess bars indiscreet or overly staged can procure real junior high "dates" through local kogaru cell-phone-sex rings. Bus stops and street corners frequently display flyers with the first names and cell phone numbers of willing schoolgirls or convincing substitutes. For a small fee, girls will come, in uniform, to pre-designated meeting places, often "love hotels" rented by the hour.

One such ring was recently broken up at a school where I was a teacher. In order to keep their preteen daughters' records pristine, none of the girls' families pressed charges. Despite the occasional incident, however, kogaru is not a synonym for "call girl." Every school has its kogaru group, and every town has streets and shops where they hang out. Kogaru is simply a fashion statement with lucrative options.

Despite their fondness for schoolgirl uniforms, those kogaru who opt to stay in school are not exactly model students. They exist solely to be "kawaii" (cute), a word they repeat like a mantra. And although they live in their uniforms, they are frequently in trouble for altering them, violating school codes by shortening their skirts, bleaching and perming their hair. Kogaru are easily distinguishable from their more serious female classmates whose hems hit midshin and who wear their glossy hair black and sensibly cut.

After reaching the age of 20 or so, the uniformed vixens graduate from kogaru status to mere garu. These things in mind, it's easier to understand why girls on the outset of adolescence might choose to outfit themselves as kogaru and buy a few more years of pimply prime. At 19, kogaru Akari is almost too old to play the nymphet.

Although business is booming at the Lullaby Pub, few men will admit to finding kogaru attractive. At least, they won't admit it to me. And yet, wander into any Japanese convenience store at any hour of night or day and you're sure to find a row of men and boys standing square in front of the kogaru manga rack. These novel-length comic books are among Japan's most popular. The artist's eye -- like the reader's eye -- is trained upward, as though he were rendering the image reflected on cleverly positioned patent-leather shoes. From this perspective, pantie-less pudenda flash beneath pleats and the undersides of breasts bulge out from middies. A penchant for kogaru manga is by no means confined to the furtive and trench-coated, either. Even mainstream Japanese fitness and lifestyle magazines occasionally include a bonus kogaru manga special, tucked among recipe cards and articles suggesting family weekend getaways.

"Teachers like the Lullaby Club," my friend Ritsuko Yamagishi tells me with a wicked grin. She herself is a teacher; we met when I was placed by the Ministry of Education as an assistant in her eighth-grade English class. She mentions several of our male colleagues' names, including that of the doughy sumo instructor who occupies the desk -- bedecked with photos of his infant daughter -- across from mine.

"Maybe," Ritsuko says, "at the club, teachers can recognize former pupils in their old junior high uniforms and feel happy and enjoy a closer look, or even invite them onto their laps for a feel."

In Japanese public schools, all forms of self-decoration are strictly policed, whether they lean toward sex kitten kogaru or drag queen ganguro. The high school at which I spent a year teaching held regular hair and face inspections. Homeroom teachers measured bangs with rulers, removed earrings from self-pierced lobes, scolded students who plucked their eyebrows and required even seniors to scrub off all traces of lipstick or powder. Before school assemblies, junior teachers were handed aerosol bottles of black spray with which to return our "kinpatsu" (golden-haired) students to regulation black. Teachers talked despairingly of "rebellious" kids who came to school with hair illicitly afuro, who rolled the waistbands of their skirts and donned slouchy rusu-socks, in flagrant disregard of the school uniform.

In Japan, uniforms are worn both in schools and workplaces, and their impact goes beyond making it easier for people to dress in the mornings. In a recent city high school debate over whether students should continue to wear uniforms into the 21st century, those in favor won with a high margin. Their main contention, that uniforms help provide "a group-feeling," mystifies most non-Japanese. The cozy concept of group-feeling doesn't even translate properly into English.

In other words, it's hard for foreigners to grasp why these "little gals" in shortened uniforms and cake makeup come across as insolent, and even, according to some teachers, "dangerous." They are refusing to conform to "the group." And in Japan, "the group" -- a system of circles within circles with Japan overlapped across the whole -- begins at, and is centered upon, school.

But strict teachers aside, there are many who believe that the ganguro and kogaru may have an impact on traditional Japan, for better or worse. According to Australian artist and Japan scholar Kirsten Farrell, these girls -- dedicated solely to the subjective pursuit of cute -- are unwitting feminists and radicals, rattling the status quo simply by hanging around, being visible and cropping up in every corner of Japan.

By showing off their indolence and trying to project an image of a life lived idly, kogaru and ganguro make a point of bucking the national work ethic. They challenge the stereotype of the average Japanese worker -- stoic "sarariimen" (salary-men) and demure OLs stashed in airless offices shuffling paper for 10 hours a day, like post-industrial cogs in a machine -- by pretending they have nothing better to do than tan, get manicures, try on wigs, flirt and giggle.

However, even if they qualified as such, there is no ganguro manifesto that unites or incites these accidental radicals. According to many Japanese young people, the kogaru and ganguro subcultures are set apart from the mainstream largely by their sexualized schoolgirl or go-go attire, and not by any distinct system of beliefs. Are these girls, with their stage makeup, body piercings and over-the-top costumes, setting out to make a dramatic statement against Japanese conformity? Or, as skeptics maintain, have the ganguro hairstyles, makeup and clothing already become a new kind of uniform?

"I hate them," exclaims 24-year-old Keiko Suzuki, assistant director of a club music program on Tokyo's MTV. "They are always at clubs like Pylon, dressed head to toe in the club's colors, dancing with each other only. They are another culture completely. I can't understand them at all. They are only show, no substance."

And while the color of their skin lends them a group identity and ganguro label, they seem to give little thought to the historical or sociological implications of their so-called blackface. An advertisement for the tanning salon "Blacky" in Egg magazine shows a close-up of a pretty African-American girl, beckoning to the reader with a crooked index finger. The italicized caption reads, "Come wid mi," -- a Japanese stab at "black English." Asked why they work so hard on their tans, why they want so desperately to approximate "black America," every ganguro I interviewed gave the same curt and unexamined answer: Because it's cool, because it's sexy.

In the words of resident high school English teacher Jenna Levy, "No one buys tall boots alone." You buy them with your friends and you wear them with your friends; it has to be a group decision or else you're going to look ridiculous. Both kogaru and ganguro are indisputable pack animals. Together they tower over the flat-heeled and the demure. Egg magazine displays spread upon spread of ganguro in groups, shot from underneath to accentuate their long brown legs. In the photos, ganguro laugh hysterically or mug goofy faces at the camera. They remind me of the popular girls in high school, working hard at looking good, working hard at looking like they're having the time of their lives, demanding constant attention and totally unsure of what to do with it once they have it.

Although Keiko Suzuki hates the kogaru and ganguro and believes they belong to a culture entirely separate from her own, she readily admits that it's dress rather than life philosophy that sets them apart. Although they model their look after prominent African-American musicians and '60s activists, their behavior falls far short of rebellious. Even critics as harsh as Suzuki are quick to point out that "these are nice girls; strange, but nice."

Akari and Haruna are nice, cheerful, willing to answer all of my questions, eager to try out a few words of junior high English. Their bashful young masuta is also friendly and eager to please. Twenty-four years old, he says he's working at the Lullaby Club to save money for a plot of land. What he really wants to do is farm daikon radishes. Akari and Haruna have no future plans, but they definitely don't want to work as hostesses forever. Akari plans on staying in kogaru uniform for another year, tops. Haruna says she'll keep her image evolving with the current Egg styles. What they both know for sure is that they want to stay cute. "Itsumo kawaii."

Whenever I stop by my local grocery store to pick up a bag of fresh udon noodles or a block of tofu, I pause to chat for a moment with my favorite cashier. Hitomi has cheeks more round and pink than most kindergartners. Last year, she was a senior in my roommate's English class at the second-to-lowest-ranked high school in the prefecture (according to a list printed annually in the newspaper). Before graduation, she spoke excitedly of the job she'd landed in the city with the New Sankyu chain of grocery stores.

In Japan, when a person is hired by a company -- even as a gas station attendant or cashier -- it is said that he or she "belongs to" the employer. This brand of "belonging" implies equal measures of employee comfort and employer control. When Hitomi took the job in the city, she was quickly installed in the New Sankyu apartment complex, located directly behind the store. It is a dreary, cement-block "Melrose Place," populated entirely by clerks and store managers too exhausted for sex or scandal. The New Sankyu apartment stairwells are festooned with row after row of freshly washed aqua uniforms hung to dry on makeshift clotheslines.

When she was still a high school student, Hitomi was often in trouble for rolling up her skirt waistband and donning "rusu sokusu," kogaru style. These days, she wears a different kind of uniform. She is seldom out of her aquas, and is often too tired to bother with changing into street clothes when she gets off work. The last time I saw the usually ebullient Hitomi, she looked pale and slack, passing foodstuffs listlessly from basket to plastic bag.

"How are you?" I asked, going as usual for the one English question she's mastered.

"Very, very bad," she said, shaking her head and avoiding meeting my eyes.

"Doushitan?" I asked -- what's wrong? -- switching into a Japanese too hushed for her coworkers and neighbors to overhear.

"Ii koto ga nai," she said. "I have no good things." She proceeded to tell me what I had been waiting to hear since September. She had taken the job at New Sankyu to earn her own money and live away from her family in her own apartment in the city. At $6 per hour, however, she could barely afford to purchase the food she spent all day shelving. She had found no love, no excitement, few friends, since moving to Kanazawa from the country.

"I'm thinking," she whispered conspiratorially, "of becoming a ganguro. At least it's something new."

That's when I noticed the midnight-blue eyelashes.

Shares