There is a large new biography of William Randolph Hearst in the stores -- "The Chief," by David Nasaw. I saw its excellent reviews, and to the extent that I am qualified I concur with them. I went through the book carefully, and with pleasure, but there is one small, piquant matter it omits. And I think it deserves the attention of this column.

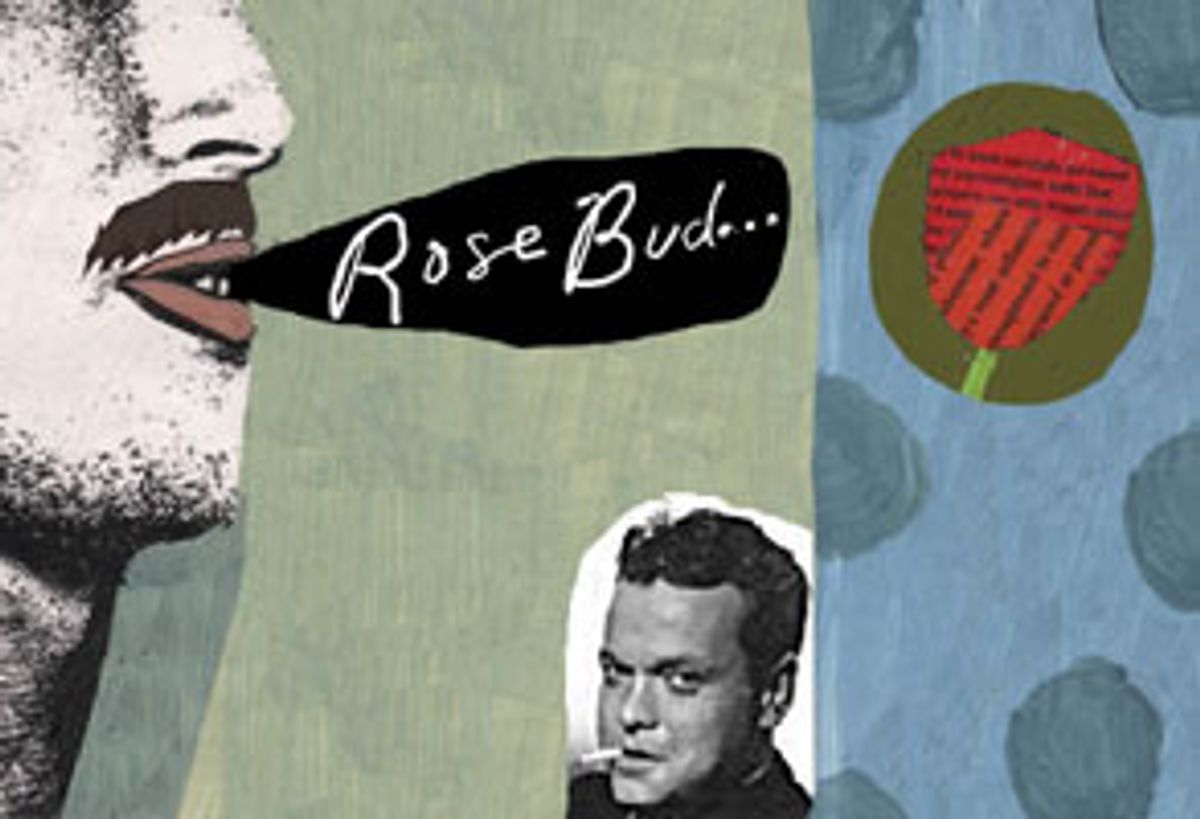

You may recall the existence of a movie, "Citizen Kane," made in 1941 by Orson Welles. Well, among other things that motion picture has always been reckoned to be a comic lampoon on the life of Hearst. Both Hearst and Kane carried mining fortunes into the newspaper business. They got involved in politics and show business. Hearst built a castle retreat at San Simeon, Calif., while Kane's was called Xanadu in Florida. Hearst had a mistress, the movie star Marion Davies, whose pictures he produced. Kane had a second wife, Susan Alexander, a "singer," and he tried to turn her into an opera star before she walked out on him.

At the start of the movie, Kane says "Rosebud" and drops dead. The film becomes an inquiry into what that word meant -- as a way of understanding Kane. It turns out to be the name of ... well, let's just say "a friendly object."

For decades, the film's impact rested there. But then, in 1989, four years after Welles' death, in a short memoir in the New York Review of Books, Gore Vidal said that "Rosebud" was also Hearst's pet name for Marion's clitoris. Now, Mr. Vidal is no mean historian -- granted that he does history his way -- and a very accomplished gossip (which may have to do with his confessed habit of never missing a chance of sexual intercourse). I believe he said that he had this clitoral inside stuff from Charles Lederer, who was related to Marion Davies and who was often a guest at San Simeon. There was no proof, of course -- though, suddenly, the big close-up of Kane's mouth, beneath the crest of mustache, saying, or sighing, "Rosebud," did take on new meanings for cunning linguists. And those of us who have always valued the wicked, schoolboy tease in Welles thought it was possible.

Nasaw is no help. Perhaps he is not the kind of biographer comfortable following his subject into bed, or love, or sex -- whatever you want to call it. And so modesty makes an ally of squeamishness and genital or clitoral history stays silent. For myself, I find Hearst the more endearing because he could be so romantic about Marion; and they stayed lovers and companions until his death. That vision of her quim is noble, touching and arousing, something the electorate deserves to know. The love language of great men and women may be more reliable as a guide to character and intent than all the promises on taxes and HMOs. There is a fixed and firm link, as organic as the clitoris itself, between intimacies and the progress of the nation.

We await response from the Bushes and the Gores.

Shares