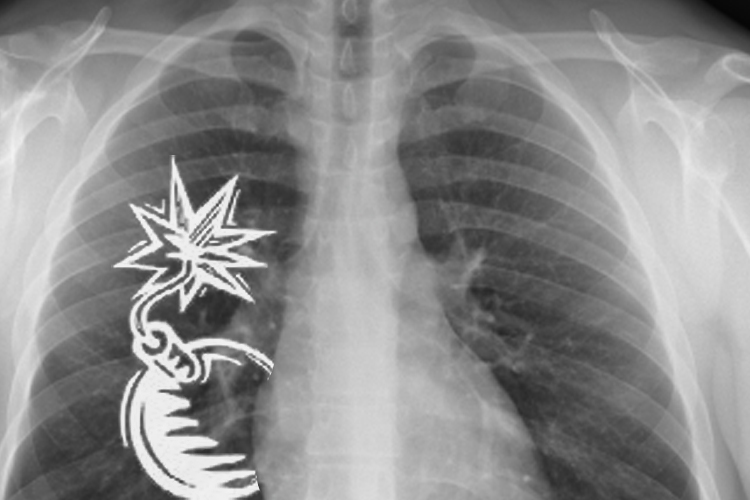

Body bombs. Last week’s big story was about terrorists planning to blow up airplanes using surgically implanted explosives.

Or the idea of it, anyway. As with many of the alerts dished out in recent years, details were vague and no specific threats were cited. It’s hard to know how seriously to take this. The successful implantation and detonation of such a device would be highly difficult, and it doesn’t take a mastermind to realize there are simpler ways of getting explosives onto a plane than having to sew them up inside yourself.

I hate sounding conspiratorial, but it often feels as if these warnings serve little purpose beyond keeping the American populace frightened and easily manipulated, lest it regain consciousness and dare interrupt the torrent of cash pouring into the coffers of the security-industrial complex.

Playing straight into the hands of the contractors and lobbyists, the press and pundits are asking all the wrong questions. The buzz is all about ways of jiggering airport security. How can we upgrade our scanners and detectors in order to meet this “new level of threat”? We’re already peering through people’s pants. Are full-on X-rays and CAT scans next?

Nobody will admit what’s obvious. First, that we cannot protect ourselves from every conceivable threat. And equally important, that this really isn’t an issue for airport security at all. As I’ve been emphasizing for years, the real job of keeping terrorists away from planes does not belong to guards at the checkpoint. It belongs higher up the chain — to the people at the FBI, Interpol, the CIA and elsewhere among law enforcement and intelligence ranks. Plots need to be foiled in the planning stage. Once a saboteur has made it to the terminal, chances are it’s too late — he or she has figured out a means of getting through.

It’s ironic how all of this got started with the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 — the common assumption being that lapses in airport security allowed the 19 hijackers to slip through unimpeded. In reality, the success of the plot had nothing to do with airport security. That the attackers made it through the checkpoint with boxcutters was and remains meaningless. They could have made knives out of anything. Ballpoint pens would probably have sufficed. They were not relying on metal blades; they were relying on the element of surprise, exploiting a loophole not in security but in our mindset — our presumptions of how a hijacking would unfold. It was elementary and brilliant, dependent on absolutely no physical weaponry beyond the steely resolve of the perpetrators themselves.

Annoyingly, here in Boston, the Massachusetts Port Authority, overseers of Logan airport, are facing a lawsuit from the mother of 9/11 victim Mark Bavis, who was aboard United flight 175 — the 767 that collided with the South Tower. United 175 and American flight 11 both departed from Logan on the morning of Sept. 11. Mary Bavis wants Massport be held accountable for lax security that, in turn, facilitated the attacks.

If Bavis insists on suing, she ought to be filing suit against the U.S. government. The 9/11 plot was always a stone’s throw from being infiltrated, and it’s possible the attacks would never have taken place if not for a lack of cooperation and the power games going on at the time between the FBI and CIA. A number of the hijackers, including Mohammad Atta, were known to both agencies and were under prior surveillance. The FBI sensed they were up to something but did not know where they were. The CIA knew their whereabouts, but did not share this knowledge in time. (This deadly misconnect is explored in Lawrence Wright’s masterful and Pulitzer-winning “The Looming Tower.”)

That, not some hapless security guard at Logan, is what allowed the scheme to unfold.

Some trivia (if we can call it such): The next time you’re flying out of Logan, look for the American flag attached to the roof of the jet bridge at American Airlines’ gate B-32. This is the gate from which AA flight 11 pushed back from. Over at terminal C, a similar flag adorns the departure point of United 175.

MEA CULPA:

In a Q&A in my post on June 30, I talked about the reasons why passengers must sometimes take circuitous routes to their destinations. The example cited was a trip from Chicago to Reno, via Los Angeles. The reader’s question described Reno being east of Los Angeles.

In reality it’s pretty much due north, as any idiot with a map can show you. This was my fault. The reader never specified whether Reno was north, south, east or anything else from Los Angeles — only that it was “the wrong way.” In my sloppy editing of the question, I added the east/west part and never bothered looking at the map.

It’s funny how you always think of L.A. as being more west than it really is.

Er, at least I do. But what do I know about geography or directions. I’m just a pilot.

QUIZ ANSWER:

Apropos of my holiday weekend in Manchester, U.K., I offered a genuine ASK THE PILOT baseball cap to the first reader able to identify which outstanding song contains the line, “Some rare delight, in Manchester town.”

As indie music fans — those with good taste — and/or anybody with access to Google will tell you, that snippet is from “My Favourite Dress,” by the Wedding Present (Mancunians, they), written and sung by the great David Lewis Gedge. The song appears on at least three Wedding Present releases: “George Best,” “Tommy,” and the BBC Sessions disk. I much prefer the former versions, which have tons more energy than the deflated BBC version.