Osama bin Laden owns Snapple.

Ironing your mail will kill any deadly anthrax spores lurking inside.

And women who want to fight terrorism should strip off their clothes and run around naked outside.

Since Sept. 11, these are just a few of the more absurd rumors and half-truths that have circulated widely in e-mail, threatening to turn the United States into a nation of naked, Snapple-boycotting women brandishing hot irons at postal workers.

But between our fractured psyches, wracked by a full-blown case of the heebie-jeebies, and all-out social chaos, stands one skeptical Los Angeles wife and husband and their trusty Web site.

Two of the Net’s most trusted hoax-busters are Barbara Mikkelson, 42, and David Mikkelson, 41, who run Snopes.com, the Urban Legends Reference Pages. Part research librarians, part gumshoes, the couple have turned their shared hobby into a public service, verifying or debunking stories that sound too good to be true.

Barbara and David met on the Net in a Usenet discussion group about urban legends, and have been publishing their truth-serum site for six years. After Sept. 11 they saw their traffic increase tenfold, as fears and theories about terrorism and war exploded exponentially.

Barbara told us what the lies, hoaxes and urban legends born of the terrorist attacks tell us about the terror in our heads.

What was the first hoax to come out of Sept.11?

The first one was up and running on that day and it was the Nostradamus prediction.

This one really grabbed people because what happened was horribly unbelievable and unthinkable. And it’s normal in times like this that people try to look to their religion, and also to the occult, to try to find some clue that perhaps they missed that would have shown this was going to happen.

As strange as it must sound, it’s far more comforting to believe that death, destruction and horror were predicted and were foreseeable than it is to coexist with the knowledge that such things can’t be foreseen; that they could happen anytime.

So, folks were quite horrified by the supposed Nostradamus prophecy, because it appeared to be an accurate representation of what had happened on Sept. 11. The implicit message was: If only we’d known, if only we’d paid attention. And of course the thing was a hoax.

How did you find out it was a hoax?

The first thing I did is I went looking in the various online repositories of Nostradamus’ writings. [And I found out that] it came off of a Web essay written by a Canadian university student, who wrote it when he was in high school. This was an essay that showed how anybody could put together an authentic-sounding Nostradamus quatrain, in that you just use a lot of important image-laden words. He went on from there to deconstruct his creation to prove exactly how vague it was and how it could be applied to anything, anytime.

On Sept. 11, people started playing mix and match with it. They started inserting lines, sometimes from real Nostradamus quatrains — create your own prophecy of doom — until they had something quite accurate about two silver birds and twin brothers and city of York.

What other hoaxes have been big??

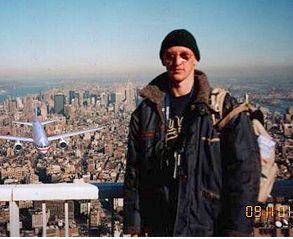

The accidental tourist — this was a deliberate hoax of a photograph of a fellow standing atop the World Trade Center tower just a fraction of a second before the plane hit the tower. This had a huge impact, [even though] it was a hoax and it was a recognizable hoax — you didn’t have to know anything about PhotoShop to know better. All you had to do is look at it and see the guy is wearing a winter coat and a wool cap.

That’s the kind of hoax that most people should have got right away, but they didn’t because they were blinded by something else — the horror of it all. They were looking at this last half-second of this unsuspecting man’s life, and the last half-second of normalcy for any of us. This was the moment — the exact instant that it stopped being a beautiful September morning and it became what it is now.

This thing showed up on the Internet about two and a half weeks after Sept. 11. At that time, people had begun to gain a small amount of distance from the horror of Sept. 11. That doesn’t mean we’d come to terms with it. But there was some sort of coexistence starting to happen. It was no longer as raw or as ripe as it has been. This photograph ripped that apart. It took people straight back to Sept. 11, to the feelings of that day. It was forwarded all over the place.

We still don’t know who the fellow was, either the fellow in the photograph or who actually put this thing together. I doubt we ever will. This fellow has a good reason to hide right now, because a lot of people are very angry about this.

Is that a common thing with other hoaxes, people being upset about being duped? Feeling like they got caught?

Honestly, you’d think it would happen more than it does, but it doesn’t. For the most part, people will generally become more angry about the substance of the story as opposed to the fact that it was a hoax and that they have been had. Look at the uproar over Bonsai Kitten.

This is a complete hoax. No cats were harmed in any way shape or form. No cats are being put in glass jars. There are no crazy Japanese out there making Bonsai pets. It doesn’t matter. People are still completely up in arms about animal abuse. You tell them that there are no animals being abused, no one has plans to, no one has done this. They’re still very angry.

We get a lot of angry e-mails about that one, because people cannot let go of the idea that this is a hoax. The feelings that it stirred up in them are just not going to be put to rest that easily.

Has it been the same way for the accidental tourist?

It certainly feels like that at this point. It’s starting to quiet down, and one of the things that helps a great deal is the number of parody sites that came up immediately afterwards where we had the accidental tourist everywhere. You now have pictures of him at the Hindenberg and the explosion of the Challenger, in the car with the Kennedys. The idea now is if you ever find yourself standing next to this fellow, run. Run fast.

What Sept. 11 urban legends are you still receiving a lot of?

Mall-o-ween. According to this very widely circulated e-mail and now a widespread rumor, a gal who had been dating a man from Afghanistan received a letter just shortly before Sept 11. In the meantime, the boyfriend had disappeared and was never seen again.

The letter she received told her not to take any airplane flights on the 11th, and not to be in any shopping malls on Oct. 31. The e-mail writer was a real person. She admitted writing the e-mail and she wrote it because this was a story her friend told her and this was supposedly what had befallen a friend of a friend.

She didn’t know the girl who had supposedly received the letter, and of course she didn’t know the boyfriend either. But she did believe the story that her friend told her, at least she did at that time. The FBI had investigated it. A key part of the story was that supposedly the letter had been turned over to the FBI, and this was added credibility. We contacted the FBI, and they said there’s no such letter.

Meanwhile the story is now being reflected back to us from Singapore and from Japan. I’ve picked up two versions where it is being told in Canada, where it’s being told as a specific warning in Canada — as in, Ontario provincial police are looking into it, and the girl lives locally.

We’re getting numerous e-mails from all over the place where people swear it is true. “My mother works with the girl’s mother, the girl who got the letter,” and this is happening in every place across the U.S. If we were to believe all the e-mails that we have received, we would have to believe that there was a woman in every city in the U.S. dating an Afghan man who disappeared, sent the same letter. It’s just amazing.

What makes that one so compelling?

First it has to do with something that is yet to take place. There is a sense of anxiety afoot here. People will not fully make up their minds about it until the 31st has come and gone and nothing has happened. Until then, they’re waiting and seeing and they’re spreading the rumor, just in case.

Second, there’s a strong component here of getting to be the bell ringer. People who forward this story on to others or who tell other people about it gain a sense of satisfaction from having done their bit to fight terrorism.

It’s empowering and it’s also a way to sort of grab the spotlight. As cold as that sounds, there is often a component of that in warnings. People circulate these ones willy-nilly partly because they want to protect those they care about, but also because it’s their way of feeling important. It’s funny because they never see how this just contributes to a growing environment of fear.

There is a third reason why it is very popular and that has to do with trying to take back a sense of control that we lost in the wake of the attacks. Terrorism can strike anywhere at any time. There are no warnings.

This attempts to take something that is completely inexplicable, that can’t be planned for, and to reduce it to a problem of if you knew the exact when and where you wouldn’t be there that day.

So, what fascinates you about these stories? Why do you enjoy tracking down the truth about them?

Part of it is a lot of these are just really great stories; they’re horrifying, they’re titillating, they’re funny.

But legends that we tell are an expression of what’s going on in society’s heart at any given moment. They’re not just random bits of lore that get dropped in here and there. It’s amazing because the stories we tell, although they generate spontaneously, end up through the process of natural selection becoming a very finely honed body of lore that reflects current society’s concerns, fears, apprehensions, morals.

People pass along a story that resonates with them. And they don’t pass along a story that they don’t identify with. Because of that the stories in wide circulation are the ones that very accurately reflect current fears, current concerns, our view of morality, what we believe is right, what we believe is wrong.

What do those three urban legends say about what our current fears and anxieties are right now?

First, we’re still trying to come to terms with what happened on Sept. 11 — the sheer horror of it, the fact that it wasn’t expected, the fact that our universe changed in the flash of a moment; even beyond the individual deaths and tragedies that have occurred here, there was this horrible breaching of a sense of safety.

Another thing that we’re trying to deal with is a growing sense of certainty that there are more acts of terrorism to come, and that this wasn’t a one-time thing, and now everyone is at risk. This wasn’t just a tragedy that’s happened that’s over. This wasn’t like the crash of TWA flight 800.

There is a very deeply perceived threat. People are trying to make their peace with that and trying to figure out what they can do to safeguard themselves, their loved ones.

Part of this is this mad scramble for information; at this point we’re not really filtering well. We’re not really discriminating that well between information and misinformation, between fact and rumor.

And at times it’s very difficult to. because often they’ll be impossible sounding stories that will turn out to be true, and the ones that nobody gave a thought to were the ones that were false.

Has anything turned out to be true that you’d thought was fake?

Oh, sure. Recently, the United pilot story. The United pilot who basically gave a pre-flight speech to the passengers who said that if any terrorists did happen to be onboard to go after them with pillows.

That’s true?

Yep.

No way.

That’s what I said. But it is true. Enough people off that flight have confirmed that yes that was pretty much the gist of the fellow’s remarks. I’ve had e-mail from these people; we’ve also seen reports written about it in other sources. The Associated Press actually got ahold of one person who was on the flight.

United has attempted to stonewall the thing. When I called they claimed they didn’t know a darn thing about it: “No, we don’t know the rumor. We’ve got other fish to fry.”

You don’t want your pilot saying: “In case our security didn’t prove to be reliable and there are terrorists onboard, please feel free to use the complimentary pillows.”

Do you think that terrorism breeds the need for these stories to explain the world to us?

Any horrific event does.

Even in more traditional folklore we have any number of myths that explain how the world came to be the way it is, and that’s because you’re dealing with the inexplicable. Why does the sun cross the sky in a certain direction every day? Why does winter always follow fall? But we also do that when we’re dealing with the truly terrifying. This is sort of our way of trying to make sense of a world that doesn’t make sense.

It’s a frightening realization that you don’t control as much of your life as you always believed you did, that so much of it is random chance. Which airplane did you get on? Or, did you get on an airplane that day? And that so much of it is unforeseeable.