For a couple of years in the late '80s, Bo Jackson seemed to be everywhere. As an outfielder for the Kansas City Royals and a part-time running back for the Los Angeles Raiders, Jackson became the first athlete to be named an All-Star in two major sports.

Jackson's prominence turned out to be short-lived. He played in only 38 NFL games and never rushed for more than 1,000 yards in a season before retiring from football after a career-ending hip injury in 1991. After retiring from baseball in 1995, Jackson returned to college to get his degree and is now co-owner of N'Genuity Enterprises, a Scottsdale, Ariz., company that specializes in food and technology services.

Today, one of the strongest reminders of Jackson's former glory is an obsolete yet still popular piece of video gaming technology. "I can guarantee that I can't go a week without someone mentioning something about 'Tecmo Bowl,'" says Jackson.

"Tecmo Bowl" is a football video game released for the original Nintendo Entertainment System in 1989, at the height of Jackson's popularity. In the game Jackson is simply unstoppable. Even though Tecmo Bo, as he came to be known, had only one play designed for him, he would regularly peel off 80-yard runs. Even if the opposing player called a play designed to stop him, Jackson was able to bust through multiple defenders for a 20-yard gain. ESPN columnist Bill Simmons has described Jackson as the greatest video game athlete of all time, and later wrote a follow-up column in which he and his readers spoke in "reverential tones" about Tecmo Bo.

Jackson's video game popularity has transferred into his real life thanks to a generation of players who grew up playing "Tecmo Bowl" as well as hardcore fans who still play the game. Countless men (they're almost always men) have regaled Jackson with stories about Tecmo Bo and often ask him to autograph a copy of the game. Jackson is happy to sign a game that he's never even played but knows all about. "What I have heard about 'Tecmo Bowl' is that I'm a bad man," says Jackson. Bad as in really, really, really good.

Jackson isn't the only athlete to have achieved fame for his video game likeness. Then-Chicago Blackhawks forward Jeremy Roenick's ability to fill the net and make Wayne Gretzky's head bleed in the "NHLPA '93" game was immortalized in the 1996 cult film "Swingers."

"It's not so much me as it is Roenick. He's good," says Trent, played by Vince Vaughn, as he dominates his friend Sue and then forces him to watch the replay of Roenick.

While most video games consist of fictitious characters and events, sports video games contain real people. And for a generation that may be spending more time in front of gaming consoles than out throwing real balls around, these video games are providing a new venue for fame and fandom. They are immensely popular and profitable, and they are changing the relationship between athletes and fans -- in many cases, the fond memories that a particular fan may have for a sports star owes more to the performance of his pixelated version than his actual on-court heroics.

In today's video games, dominant players like Roenick and Tecmo Bo are much harder to find. The relative simplicity of past sports video games created extremes in the quality of individual players and teams. Producers at EA Sports, the world's largest producer of video sports games, believe that no athlete will ever be able to dominate a game in quite the same way as Tecmo Bo.

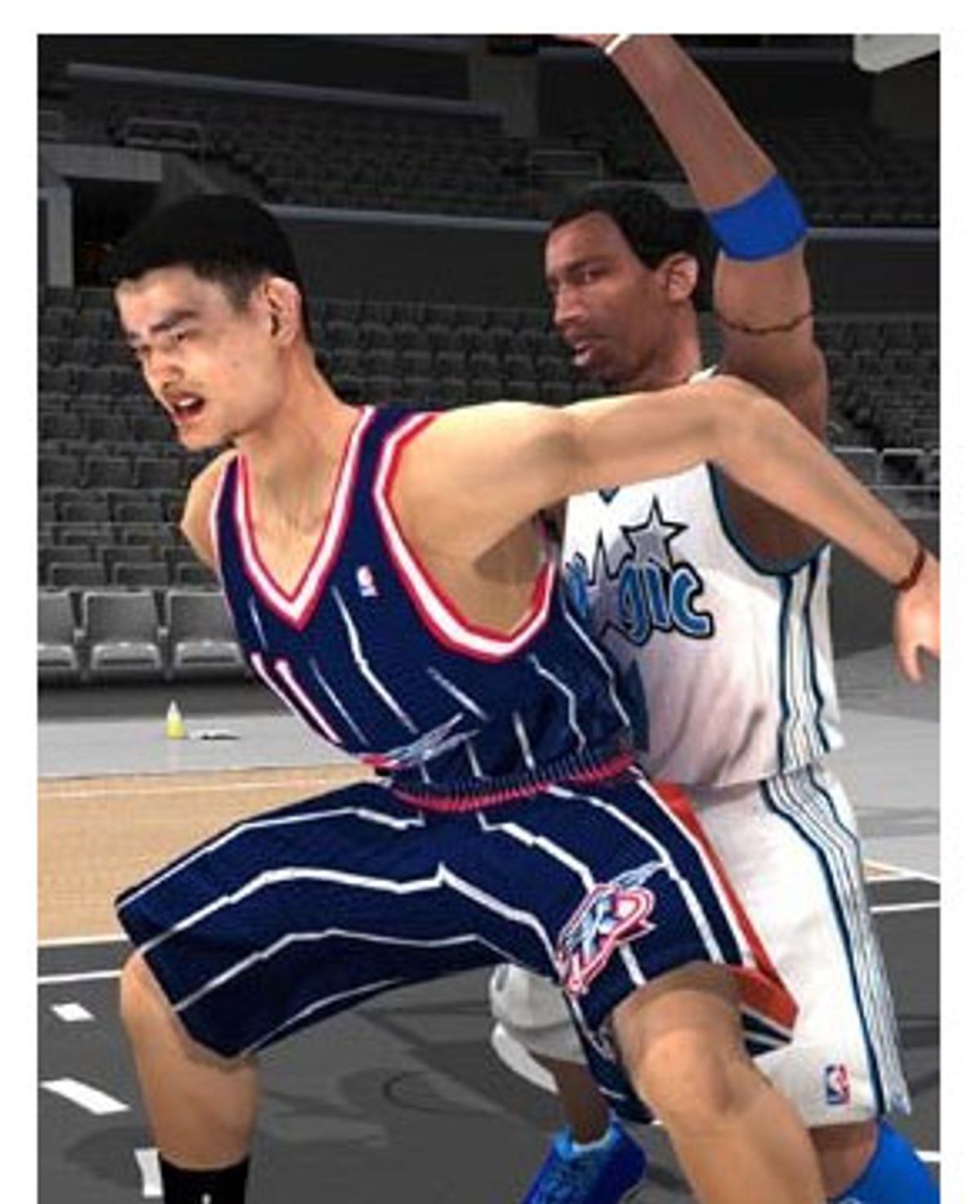

"We make a conscious effort that things like that don't happen, because it takes the fun out of the game," says Tim Tschirner, a producer of EA's million-selling "NBA Live 2004." "We want the players to be rated as objectively as can be."

"NBA Live" producers rate all 300-plus NBA players in 30 different categories on a scale of 1 to 100 in order to accurately translate an athlete's real-life skills into its games. Roughly half of the categories are based on real-life statistics such as three-point shooting ability and free-throw shooting. The EA production team then watches hours of videotape on each player to assess speed, agility, strength and other qualities that can't easily be measured by numbers.

While video game producers have greatly improved their ability to gauge each athlete's abilities, player performance can be wildly unpredictable. Rookies are a particular problem since no one can accurately forecast how they will fare at the professional level. Producers try to counteract such problems by providing several updates a year via the Internet.

Today's video game producers pride themselves on their games' verisimilitude, but there are some critical differences between sports video gaming and the real thing. As anyone who has sat through the fourth quarter of a 30-point blowout can tell you, real sporting events can often be anything but entertaining. Video games can't afford the luxury of garbage time and must tweak reality to hold your attention better than many real sporting events. "It's picking the most exciting elements and trying to make them happen a little more often," says "NBA Live" producer Todd Batty, from his office at the EA Studio in Vancouver, British Columbia.

"We're trying to portray those athletes as heroes," Tschirner adds. "That's what they are. They're heroes on your TV screen that may be a bit over the top but not by that much."

That slightly heightened version of reality can leave gamers with a distinctly different impression of the athlete. Average players become good players and good players become superstars with a knack for making dramatic, game-winning plays.

While "NBA Live" producers note that most users follow the NBA closely, there are still plenty who get their information about players solely through video games. Many of Seattle Supersonics forward Rashard Lewis' younger relatives relate to him through the game. "[I have] family and friends that watch the NBA but don't watch it every day and really follow the season," says Lewis. "They play me on the game more than watch me play on TV."

Video games can give a user a skewed perspective of an athlete's real performance, especially for those who don't follow the sport closely. Football fans got to watch precious little of Atlanta Falcons star quarterback Michael Vick this season because he missed 11 games with a broken leg. For players of "Madden 2004," however, Vick is one of the best video football players of the last decade. Even gamers who follow sports closely can have an altered view of athletes. While most fans spent last season watching Vick on the sidelines in street clothes, "Madden 2004" players got regular reminders of Vick's offensive brilliance.

Video games also showcase the skill of athletes without the unpleasant aspects of reality getting in the way. In video games, there are no contract holdouts, no drug busts or ugly sexual assault cases. L.A. Lakers fans may feel conflicted about cheering for embattled star Kobe Bryant, but choosing to play the Lakers in "NBA Live" is an easier decision, since the Lakers are one of the game's top-ranked teams and can help a gamer beat the computer or his friends.

That competitive aspect helps gamers feel more connected to the athletes. Roenick recently told NHL.com: "College kids come up to me and say that they made it through college simply by playing myself on the video games in their video game bets or their weekly playoff games. They've told me that they won money simply because they were me in their video games because I was a stud."

In dorm rooms, rec rooms and wherever else young males gather to avoid the real world, friends compete against each other for money or bragging rights. If using a particular athlete can help someone beat a friend, they may feel a connection to the athlete that is stronger and more complicated than mere fan worship. "You're controlling him," says Batty of the video game athlete, "but he is making you better because he's better in the game."

A good performance in a video game is something that can have a lasting effect. EA producers claim that most of its consumers buy the new version of their games each year, but many gamers play the same version of a game for three or four years or even longer. Bo Jackson's short burst of greatness has lived on in "Tecmo Bowl" for more than a decade.

The importance of video games to an athlete's public image is something that the athletes themselves are acutely aware of. EA producers regularly hear comments from athletes about their video game likeness. Sacramento Kings guard Mike Bibby once asked "NBA Live" producers why he wasn't able to dunk in "NBA Live." The producers then mentioned that it was because he doesn't dunk in games. "They don't have me dunking," says Bibby of "NBA Live." "No one thinks I can dunk because I don't dunk in games, but I can."

Athletes also care about their video döppelgangers because many of them are avid gamers who grew up playing video games. As several Sonics players sit in the locker room an hour before tip-off, one mention of an old-school video game like "Tecmo Bowl" sets off waves of nostalgia.

"That's the best game ever," says Sonics All-Star Ray Allen of "Tecmo Bowl" as he lies on the floor doing some pre-game stretches.

"Everybody wanted to be the Raiders or the Giants," adds guard Ronald Murray.

A lively discussion ensues about Jackson and other "Tecmo Bowl" greats like Lawrence Taylor, Walter Payton and Jerry Rice. Murray and guard Antonio Daniels then try to name all of the fictitious fighters on "Mike Tyson's Punch-Out," a Nintendo boxing game featuring Tyson and a series of fictitious fighters. Daniels quickly rattles off the names of imaginary boxers like Don Flamenco, King Hippo and Soda Popinski, a hard-drinking Russian boxer who would taunt his opponents by saying, "I can't drive, so I'm gonna walk all over you!"

As Rashard Lewis watches his teammates reminisce about their years spent in front of the warm glow of a Nintendo, he realizes that the games his nieces and nephews are currently playing may become a strange part of his legacy. Right now, the 24-year-old is a promising young forward with All-Star potential, but if he's lucky he may someday be remembered as fondly as Tecmo Bo, Jeremy Roenick or, for that matter, Soda Popinksi. "I've never thought about it, but now that you mention it, it is kind of weird," Lewis says. "Especially in the future when I get older and not in the NBA anymore. You have new games with all the new faces on there every year, but people remember those old-school games. It's kind of a cool way to be remembered."

Shares