Build a better mouse trap, catch more mice. Build a better online gaming server, get yourself sued. That is what’s happening to the developers of bnetd, a software program for Web servers that duplicates the functionality of Battle.net, Blizzard Entertainment’s hugely popular online gaming service.

Ross Combs and Rob Crittenden, two of the lead developers on bnetd, say all they ever wanted to do was create a place to play best-selling Blizzard games like Starcraft and Diablo in a friendly online atmosphere free of the technical bugs that plague Battle.net.

Anyone who has ventured on to Battle.net to wage war against aliens or to hack and slash through dungeons is likely to appreciate the sentiment. Battle.net’s popularity has been one of its great drawbacks. Frequent crashes and slow response times due to a huge crush of players — especially right after the release of a new game — can often make Battle.net an unpleasant experience. The technical problems are exacerbated by social malfunctions: the malicious killing of some gamers by other players and the proliferation of hacks that give some players unfair advantages.

It all added up, recalls Combs, into making Battle.net a scene that “just wasn’t a fun place to be.” So, in classic geek fashion, coders like Combs wrote their own, free software version of Battle.net. With bnetd’s code anyone could set up their own server for playing Blizzard games, and since the code was open to the general public, they could even modify it themselves if they so pleased.

For Blizzard, fun isn’t the issue. The problems are copyright infringement and the promotion of piracy. And with a highly anticipated new game, Warcraft III, poised for launch this summer, the company is playing hardball. On Feb. 19, Blizzard sent a cease-and-desist e-mail to Internet Gateway, the ISP that hosts the Web site for bnetd. In language that is fast becoming the scourge of the Internet, the letter declared that “pursuant to the provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act” (DMCA), the bnetd code was “circumvention technology” which permitted the violation of Blizzard’s copyrights.

Specifically, Blizzard charges that bnetd allows the use of pirated copies of its games to be played on servers running bnetd. (In comparison, pirated Blizzard games won’t work with Battle.net.)

In response, the bnetd team, unable to face the legal costs of contesting Blizzard in court, removed the bnetd code from the bnetd.org Web site. But this did not satisfy Blizzard. On April 5, Blizzard filed suit against Internet Gateway and bnetd.org’s system administrator, Tim Jung. (Other defendants, perhaps those who contributed to bnetd’s code, may be added later.) This time around, Blizzard did not cite the DMCA. Instead, Blizzard now says that bnetd serves as a way to allow unauthorized public performances of Blizzard’s copyrighted work (its games).

It is unclear exactly what the reasoning was behind the change in legal tack. Blizzard’s legal team may have decided that the charge that the bnetd code itself was a copyright violation would not stick — the code “emulates” the functionality of Battle.net, but it does not actually copy any of Battle.net’s code. It’s also possible that the new legal language was a pre-emptive attempt to protect a new, subscription-based version of Battle.net that will debut for the upcoming World of Warcraft.

In a statement sent by e-mail to Salon, Michael Morhaime, Blizzard Entertainment’s president and co-founder said, “We always have been and will continue to be diligent in protecting our trademarks and copyrighted materials. We are convinced that certain members of the bnetd project illegally copied parts of our code and bypassed the game’s CD-Key authentication process. We further believe that emulators damage our efforts to prevent piracy, and they create safe havens for players using illegal copies of our products.”

Whatever the case, to some observers, the new charges are even worse than the original.

To say that bnetd allows unauthorized public performances implies that it is a copyright violation just to create software that “interoperates,” or is otherwise compatible, with Blizzard. Interoperability — which enables software to work with other software — is a core principle of how the Internet, or any computer network, works.

The stakes are high enough that the Electronic Frontier Foundation has joined the fight, agreeing to provide legal representation for the bnetd team. Bnetd thus joins the fast-growing list of other software causes célèbres — Dmitry Sklyarov, 2600 Magazine, Napster — that have emerged in the hotly contested war over intellectual property and the Internet. How the Net works in the future could be decided in skirmishes like these.

“It is unfortunate that the state of U.S. law has fallen to such a low as to affect programmers in this way,” says Crittenden, 34, who lives in Lithicum, Md. If the bnetd team happens to lose its case, he speculates, “Any company could create their own mini-monopoly on network communications. It could bring down the interoperability of the Internet.”

Bnetd’s roots go back to the 1998 launch of the real-time strategy game Starcraft. Mark Baysinger, a Starcraft fan who was reportedly dissatisfied with the experience of playing the game on Battle.net, created a program called Starhack that duplicated the functions of Battle.net. Baysinger also received a cease-and-desist letter from Blizzard, but after a few weeks of back and forth, no legal action resulted.

Baysinger eventually moved on to other things, but his decision to “copyleft” his code under the GNU General Public License (GPL) ensured that other coders could pick up where he left off.

The basic principle involved reverse engineering the functionality of Battle.net by intercepting the packets of information that a game on a user’s computer would send to Battle.net and figuring out what those packets were supposed to do. According to some legal experts, such reverse engineering is not in and of itself illegal, although the language of the DMCA has muddied the waters considerably on the question of what is and what isn’t allowed.

As for Blizzard, the company’s statement declares flatly that “it would have been impossible for a third party to recreate specific authentication code embedded in their games by analyzing or ‘packet sniffing’ network traffic between a Blizzard game and Battle.net.” According to Blizzard, the lawsuit filed on April 5, 2002, “alleges that members of the bnetd project violated copyright law by illegally copying portions of code from Blizzard’s computer games.”

Specifically, the statement declares that “in order to make the bnetd software work, certain programmers at bnetd copied Blizzard code relating to password and username authentication, and incorporated it into the bnetd server program.”

But according to the bnetd developers, there was never any intent to encourage piracy or to otherwise financially gain at Blizzard’s expense.

The 27-year-old Combs, one of the programmers who picked up the reins from Baysinger, says a big motivation behind the creation of bnetd was to facilitate private gaming sessions among friends and online colleagues who would be respectful of one another. When the first Starcraft game was released in 1998, he says, problems soon became apparent with its Internet gameplay feature. Many players on the Battle.net servers seemed to thrive on abusing others. Playing with strangers often resulted in unpleasant surprises: It wasn’t atypical for the person you were teamed with as a partner to unexpectedly switch sides and become your opponent (that wasn’t intended as a feature of Starcraft’s gameplay on Battle.net). The use of program hacks, which let some players cheat, was also a rampant problem.

“Now, I’m sure it wasn’t all bad,” says Combs, “but I know several people that were burned early on and never went back. My personal reason for working on bnetd was to provide a nicer gaming environment for my friends.”

The open-source nature of the project has other implications as well, which may have inspired some of the legal problems. In February, Blizzard released a beta, or test, version of Warcraft III that could be played only on Battle.net. Shortly after the beta release, some programmers began an offshoot of bnetd called WarForge that would allow Warcraft III beta testers to play without jumping through Battle.net’s hoops.

But many of the bnetd developers say they opposed adding Warcraft III support before the game’s official release (tentatively slated for this summer), because they were concerned that it would encourage the pirating of the beta for playing on servers running bnetd.

“We had nothing to do with the addition of Warcraft III support,” says Crittenden. “[But] we are an open-source project and anyone is free to [develop] their own version, and this is what WarForge did. We don’t agree with their use of hacks to get Warcraft III to work.”

Did WarForge’s appearance trigger the latest round of legal fire-fighting? Blizzard isn’t saying, but along with the upcoming release of Warcraft III, Blizzard is reportedly planning a new World of Warcraft multiplayer online version of the game that will be subscription only.

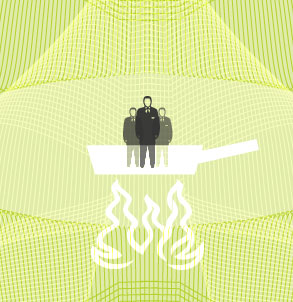

In any event, now that Blizzard has turned on the legal heat, bnetd has become a symbol of a fight that means a little bit more than just the opportunity to play Diablo online without getting killed by another player: It has become the latest hot-button for intellectual property and the DMCA. So the bnetd developers, with help from EFF, are going to fight.

“I have complained about the DMCA regularly for years,” says Combs, “so it is only right that I would not roll over when it was waved in front of me.”

“[The cease-and-desist e-mail] was one of the more egregious examples of overreaching we’ve seen under copyright law and the anti-circumvention provisions of the DMCA,” says Cindy Cohn, a legal director with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “We at EFF have been alarmed at the growing number of cases where the anti-circumvention provisions of the DMCA and claims of copyright infringement have been misused to try to scare people out of exercising their rights. We saw Blizzard’s letter as another of those, and one that clearly had no foundation in the law.”

EFF, which has also taken a lead role in defending Russian programmer Dmitry Sklyarov on charges of violating the DMCA, decided to jump into the fray.

“We thought that the attack — [on] a volunteer project that simply sought to create an interoperable computer program — could have broad ramifications for the future of reverse engineering, especially for the free-software and open-source communities,” says Cohn.

Combs and Crittenden say they have been receiving strong support from other programmers and software developers. The few negative responses sent their way have been based on misunderstandings about bnetd’s purpose.

“Many seemed to think that we were simply around to let people who had pirated copies [of Blizzard games] play against each other, which isn’t the case,” says bnetd developer Crittenden.

To address this matter the bnetd developers would like to offer Blizzard a concession: to include code that would make bnetd servers work only with legitimate copies of Blizzard games, not pirated ones. Doing this, though, would require cooperation from Blizzard, since such a security check would need to access Blizzard’s online database that identifies legitimate copies of its games.

However, Cohn points out that putting in anti-piracy measures isn’t even something that the bnetd team is legally obligated to do: “The bnetd code has many reasonable uses that have nothing to do with piracy. It should not be banned just because it can also be used by infringers to play games. In fact, the bnetd code is even further away from piracy than the VCR. The VCR actually makes infringing copies. Here, the bnetd code doesn’t do the infringing — it just allows both infringing and noninfringing games to play.”

“This reminds me a bit of the Aibo pet case, where Sony threatened one of its customers who wrote a computer program that made the Aibo do more tricks than Sony intended,” says Cohn. “Fortunately, Sony had the wisdom to withdraw their threat once public outcry began. Here, Blizzard is suing its customers for making a server that has more functionality and provides a better experience — by letting you play with just your friends and other things — than they do.”

Aside from the piracy issue, Combs says that he doesn’t “understand how we are threatening [Blizzard’s] business. Battle.net is a free service to anyone with a copy of any recent Blizzard game.” Blizzard makes money from the games sold, whether they are used on Battle.net or not. Just as Battle.net exists to improve Blizzard’s sales by adding value to its games, bnetd does the same, the bnetd developers argue.

But what happens if, as speculated, Blizzard turns Battle.net into a subscription-based service? The company’s upcoming World of Warcraft will be a persistent online world where the gameplay runs nonstop, and for which players will probably need to pay. Combs says that even then Blizzard still needn’t be concerned about bnetd. Updating and maintaining the gameplay for a persistent online world requires much more time and money than hobbyist programmers and gamers could ever provide.

However, he admits that bnetd does remove a large measure of Blizzard’s control over its products. Through Battle.net, the company can keep track of a game’s popularity and usage patterns, and force players to view advertisements hyping its upcoming products. Additionally, Blizzard can alter features of the games on Battle.net. When Blizzard decides that bots — automated software assistants — are no longer allowed, then that decision is final. When moderated private chat channels are disabled, there is no recourse. The bnetd developers feel that users should be able to choose whether they want to accept these changes or not.

While the EFF confidently believes that bnetd’s chances of prevailing over Blizzard are “very good, and even better if Blizzard’s customers begin to speak up,” Cohn points out what could happen if things turn out otherwise: “If bnetd can be successfully sued, many other reverse engineering projects, both open source and not, are at risk.”

A loss for bnetd could also have implications beyond emulation. Theoretically, it could affect companies and hobbyist programmers who create programs that are compatible with other products. The very concept of compatibility as a feature in software and hardware could be brought into question. And that’s a loss that could be a bit more severe than the typical bloody ending to a game of Warcraft.