The treasury markets are nervous again, we are told. Last week, three separate auctions for treasury notes attracted less than enthusiastic bidding, sending yields on the 10-year bond to their highest point since fall 2008. On cue, Alan Greenspan immediately labeled the yield spike the “canary in the mine” — warning that market participants are finally registering their terror of “this huge overhang of federal debt which we have never seen before.” The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and the Financial Times all promptly expressed dour foreboding.

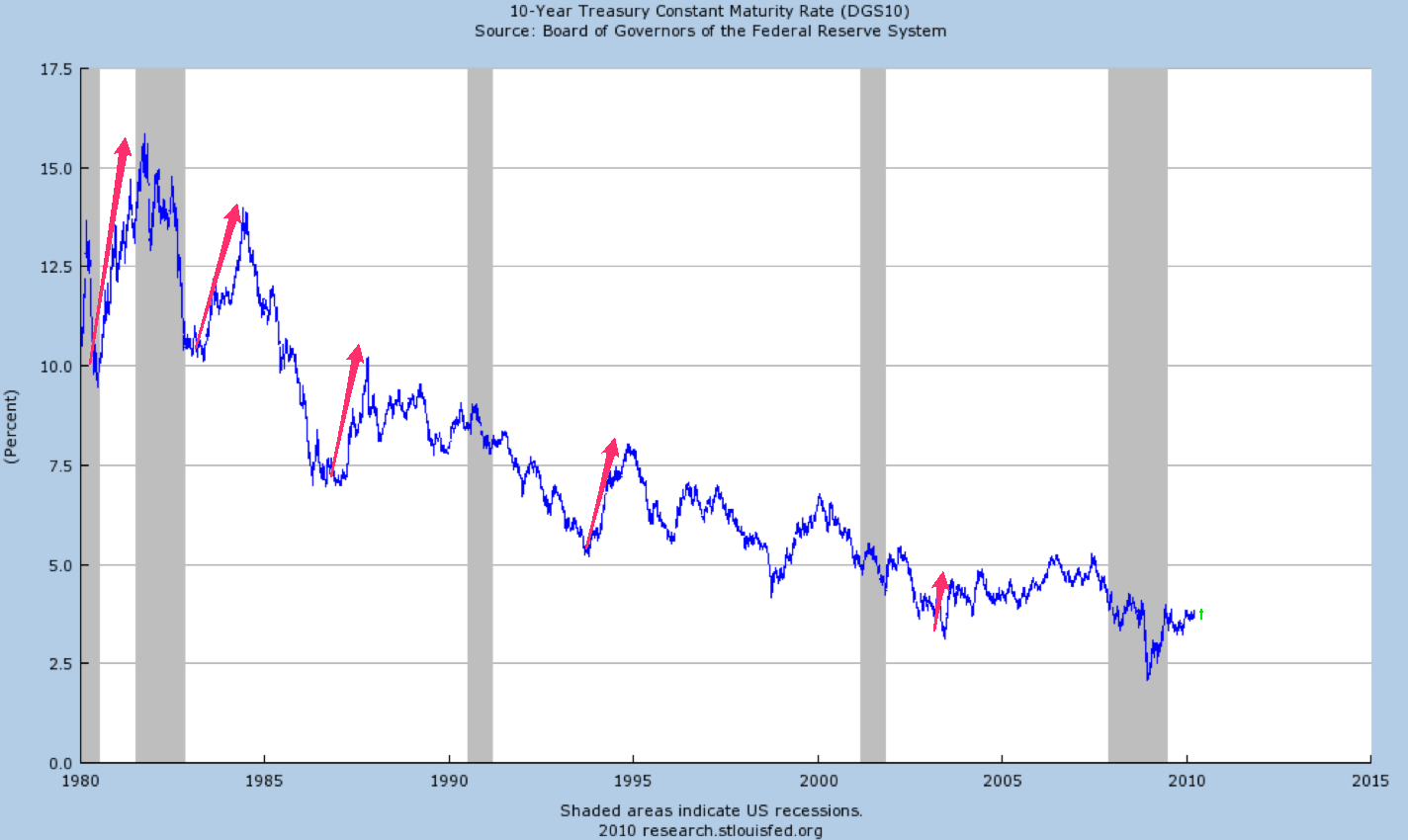

Not to worry, Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong said immediately, rushing to the scene like the econoblogospheric equivalent of Keynesian paramedics. By historical standards, borrowing costs for the U.S. government are still quite low, and they’ve got the charts to prove it. Don’t let the bond vigilantes spook you!

Steve Waldman and James Hamilton chimed in with interesting technical takes. For meta-summaries, Ryan Avent and Felix Salmon both concluded that it is very hard to come to a conclusion. One crucial problem: The political and economic implications of a long-term rise in treasury yields are so immense that it is impossible to evaluate the merits of any individual piece of analysis on this topic without considering the agenda behind it. For example, if you are more afraid of the consequences of big deficits than you are of a relapse into a double-dip recession, you are likely to be more willing to harp on every upward tick in treasury yields. Likewise, it’s pretty clear that conservatives care far more about deficits when a Democrat is in the White House — somehow the bond vigilantes never come out after dark to mug Republicans.

But what really makes this story messy is the fact that a declining appetite for treasuries can be plausibly interpreted as either a fear of unsustainable deficit spending or a return to economic health or both.

A couple of paragraphs in today’s Wall Street Journal treatment of this evergreen story help illuminate this dynamic. (Italics mine.)

Investors were awaiting the key event of the week: Friday’s nonfarm payrolls report, which comes ahead of the market’s early, noon close for the Easter holiday. Expectations are that the report will show that the economy gained 203,000 jobs in March, according to a Dow Jones Newswires survey of economists, which would be its second and largest increase since the recession started. Economists also expect the unemployment rate to remain at 9.7 percent.

A much larger-than-expected gain in March jobs would likely spark another rout in Treasurys, as expectations that the Fed could start to tighten monetary policy sooner than expected increase. A lower-than-expected gain, or a loss, would reinforce the Fed’s continued reassurances that interest rates will remain low for a while as the economy heals, helping Treasurys.

Let’s unpack this. A good job number will be bad for treasuries, because of fears that the Fed will tighten monetary policy by raising interest rates. Bad news for treasuries, theoretically, is bad news for the government, because borrowing costs will rise, thus placing even more pressure on government finances.

But one reason why the government is borrowing a lot of money, aside from the various left-over unfunded profligacies of the Bush administration, is to pay for the stimulus and the automatic increases in social welfare spending that are a direct function of the recession. A “much larger-than-expected gain in March jobs” would be the best possible signal that the economy might be about to turn the corner — which would lead, in turn, to lower social welfare spending, higher tax revenues, less pressure for additional stimulus, and, ultimately, a lower deficit.

In other words, a key contributor to bond investor nervousness is a robustly growing economy, but a robustly growing economy is exactly what we need to assuage bond investor nervousness.

In the end, it’s all about balance. At that precise moment when we can be confident that economic growth, complete with vigorous job creation, is sustainable, then and only then would it be appropriate to make deficit reduction the main priority. But it is very, very hard to know for sure when we’ve reached that point, a difficulty that is compounded by the proliferation of explicitly political agendas that swarm in every basis point uptick or downtick.