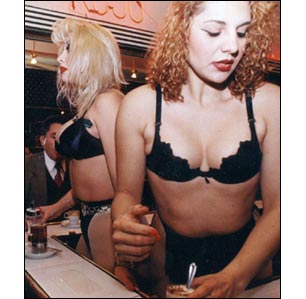

While the rush-hour swarm of office workers heads out of downtown, more than a few stay behind to cram into the tiny Cafe Ikabar. The coffee’s good, but it’s not what reels in the customers — even owner Victor Trujillo admits that. What’s more, the absence of chairs makes the place hardly ideal to unwind in after a stressful day at work. Luring the crowds are the sirens behind the faux-marble bar: a trio of nubile waitresses wearing little more than glossy smiles and crimped hair.

Before an enthralled audience of mostly middle-aged men, the curvy barmaids sashay with their coffee orders along a platform several inches high. Outrageous heels add even more height, guaranteeing the customers a nearly eye-level view of the women’s buttocks; each plump, glistening pair divided by a leathery bikini back verging on thong dimensions.

Dozens of other, similarly brazen, daytime coffee bars pepper the otherwise-drab business district of Chile’s capital. Known locally as cafes con piernas — cafes with legs — they run a wide spectrum of raciness. In some, the women are dressed only a tad more risque than, say, early Madonna. In others, sheer lingerie allows customers to check their imaginations at the door.

What many find most fascinating about this business is its recent and booming success in a society that’s widely considered Latin America’s most culturally conservative. Divorce is still illegal here, and many private schools have a policy of expelling students whose parents are separated. Abortion is prohibited even when the woman’s life is in danger. Censorship boards overseeing film distribution and television programming wield inordinate power. Theaters — even adult ones — were barred from showing Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ.”

The cafe owners cite “convenience” as key to the industry’s popularity. “Before, a man who wanted to see a beautiful girl had to shut himself up in a nightclub, and arrive home late,” says Miguel Angel Morales, standing in front of his notorious Baron Rojo (Red Baron) cafe. “Here, he drinks his coffee, and five, 10 minutes later, he leaves and goes home or to work. There’s nothing more to it than that.”

Critics contend there is more to these cafes than men merely ogling at women over a cup of cappuccino. Allegations of prostitution led the mayor of Providencia, the wealthiest district bordering Santiago’s business center, to shut down three of them.

Lorena Maureira, a chatty 20-year-old waitress at the Cafe Cartms, doesn’t doubt that some rival cafes con piernas are a front for the world’s oldest profession. Still, she insists that the closest thing to sex most offer are just fantasies, or a kind of proxy girlfriend. Her many regulars are “guys who are like friends [and] come in to joke around,” says Maureira, who, under the soft red light of her workplace, could pass for Penelope Cruz, if the slim Spanish actress were to chunk up a bit.

Whether or not the cafes actually peddle their waitresses, they still cater to men who long to play sex roles reminiscent of the now-faded whorehouse, says Raquel Olea, a prominent Chilean feminist and literary critic. Once a staple of nighttime entertainment for Chilean men living in or near small towns and cities, brothels were already dying out in the ’60s, observers note. Finally, the coffin was sealed by the curfews imposed after dictator Augusto Pinochet came to power in the country’s bloody 1973 coup.

Olea muses that a barmaid friendly with a regular might confide her problems to him, and sigh about having to bare so much to make ends meet or to feed her fatherless children. “I’m sure many of the waitresses tell their customers how they yearn to do something else,” she says.

According to Olea, romanticizing his favorite barmaid’s hapless situation enables a guy to play the traditional roles of protector and provider, as he’s bound to leave “his girl” a tip that’s disproportionately large for a few cups of coffee. The cafes are basically a safe, cheap venue for men to indulge their fantasy of “protecting weak women in a place of desire,” the literary critic says.

Olea also points out that the relationships cultivated there “have no place” at the office, which is where most customers are either going to or coming from. With the percentage of women in the labor force rising and the tolerance of sexual harassment in the workplace diminishing, the machista impulses Chilean men can unleash at the cafes have to be stifled for most of the week. For these poor guys, Olea says, the cafes are “a little valve” to decompress during the workday.

Regardless of what’s nourishing the industry’s growth, the appetite for these daytime purveyors of cappuccino and leggy fantasies remains hearty. Reliable figures on profitability are hard to come by, but owners maintain that margins are fat. Morales says his Baron Rojo, which is no bigger than a small bar, serves between 800 and 1,000 customers a day, with a cup of coffee priced around 590 pesos (U.S.$1.15). “The business is very secure,” says Trujillo.

Their success also beefs up the waitresses’ salaries. Although these women are usually paid the minimum wage of 90,500 pesos ($177) a month, Morales says tips can boost that figure to well over 600,000 pesos, tripling the income of the average working Chilean. “I make a lot more than a waitress at a regular establishment,” boasts Carolina Scarlet, who has tended bar at the Baron Rojo for two years.

Gliding back and forth on what’s effectively a catwalk, Scarlet, 19, swiftly fills orders while a bright-red headscarf — matching her string bikini — keeps honey-blond curls tightly under control. The waitress implies that customers are kept in line just as easily: “I know how to handle a guy who gets fresh,” she warns.

Three cafe con piernas chains have been around for roughly four decades: The Cafe do Brasil, Cafe Caribe and Cafe Haiti. However, the number of locales only began soaring in the mid-’90s, when upstarts challenged the triumvirate’s hegemony by showing more skin.

It was Morales who upped the ante five years ago with the debut of his now-infamous Baron Rojo. Others promptly followed suit. Brasil, Caribe and Haiti stood their ground against the onslaught, and remained tamer than most of their young rivals. No matter how short and constrictive the uniforms at the traditional chains get, they are still clearly outerwear. Waitresses at the Baron Rojo, Cartis and Ikabar expose much more flesh, pushing espresso in the skimpiest of lingerie.

One wardrobe item, however, appears to be de rigueur across the industry: sparkling, flesh-tone hose.

The authorities evidently distinguish between the two types of cafes. The three oldest chains operate locales where glass walls effectively put on display the waitresses cocooned in their little numbers. The racier upstarts have been ordered by the mayor of Santiago’s downtown district to tint their windows. “There isn’t exactly a law,” Trujillo explains, “but municipal inspectors come around to make sure the windows aren’t completely transparent.”

In the case of the Ikabar, a wide band of blurry glass runs horizontally along the windows and otherwise fully transparent doors. The visual rewards are slim for the titillated passerby taking a quick glance: At best a few silky calves, stiletto heels and loud platform boots are visible below the frosty strip, as well as the invariably rococo hairdos towering above. Still, a band of gawking men and boys — some crouching down, others on tiptoe — are always assembled right outside.

A mandated darkening of their windows isn’t the only problem facing the cafe owners. Trujillo gripes that obtaining business permits from the authorities has become virtually impossible. What’s worse, he adds, is that more and more downtown galleries with coveted locale space are shunning the cafes, perhaps to avoid offending family shoppers. “There are a lot of limitations on setting up new cafes,” he complains.

Despite obstacles to the industry’s growth, and the perception of many Chileans that working there amounts to prostitution, the cafe owners say applications keep pouring in.

Good pay isn’t the only attraction, the barmaids say. Scarlet, for one, claims that the cafes are far more savory than working in a topless bar, where easy-flowing alcohol means customers can get ugly. Maureira agrees. Just the thought of “some drunk guy who wants to touch you” makes her cringe.