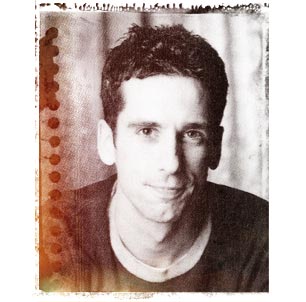

Has Dan Savage, writer of “Savage Love,” a deliciously raunchy sex column read by 4 million people every week, been tamed? Can we still address him, as we always have in print, as “Hey, faggot!” ? Or do we call him Daddy? He has, after all, settled down, adopted a son and written a surprisingly moving memoir of the experience called “The Kid: What Happened After My Boyfriend and I Decided to Get Pregnant.”

The book, just published by Dutton, chronicles the remarkably short journey that Savage, whose column appears in 35 newspapers, and his boyfriend take to achieve fatherhood. Despite the expediency of their experience, the book is full of twists and turns, each subjected to Savage’s snide and penetrating wit. And in an uncharacteristically wide-eyed mood, Savage provides a lovely tale about the thrill of anticipating a baby — even when it isn’t yours (by birth).

At a time when the gay-rights movement obsesses about same-sex marriage, Savage and Miller skipped the mundane battle and went straight to the rewards. They don’t get married, they get pregnant — sort of. It was a controversial move — not just in the eyes of the usual queer-bashing suspects, but even among some of Savage’s close gay and lesbian friends who accused him of selling out on years of gay liberation by embracing a heterosexual tradition.

Savage weathers this criticism much as he weathers all criticism, with acidic humor and very little genuine concern. Straight people have kids to make their lives more meaningful, says Savage, which essentially boils down to needing a hobby. Gay people need hobbies, too, he whines, and the idea of raising a family seemed more enticing to Savage and his boyfriend than the muscle, sex and Fire Island alternative or the DIY-home project, Martha Stewart, Graves tea kettle route favored by the over-30 urban gay population.

Savage even confesses some dubious reasons — like perking up a pending book deal — for the adoption. But he is quick to remind readers that he and his partner started the “lifelong adoption process” before he thought of writing a book about it.

When Savage, 34, met and fell in love with Terry Miller, 10 years his junior, both established quickly that they wanted kids. Two years into their relationship, the pair settled on a “lesbian-free baby option” by visiting an adoption agency. The Seattle couple chose to adopt in Portland, Ore., home to state laws favorable to adoptive parents — a father who is absent at birth and six months after, for example, has no right to legal guardianship.

Ultimately Savage and Miller settled on open adoption — a method that allows the birth mother to choose the adoptive parents and continue to have a relationship with the child throughout life.

Savage writes in his book that between six and 14 million children are being raised by gay or lesbian couples in the United States. It’s a statistic that he believes will make it difficult for religious fundamentalists to legally challenge gay adoptions. Florida is currently the only state with a law that forbids adoptions by gay couples. Attempts to pass similar laws in Texas, Indiana, Utah, Oklahoma and Arizona have not been successful.

In an interview, Savage talked about his book, the experience of adopting as a gay man and his life as a father to son Daryl Jude.

Why did you decide to adopt?

I’m allergic to dogs, so I couldn’t even adopt what gay men typically adopt when they have that maternal gene. We don’t have uteruses and we can’t just go out and buy $100 worth of sperm and knock ourselves up, much as we might enjoy trying. Adoption, ironically, is also the most autonomous and powerful way for gays to make a family. For most straight couples, adoptions are the least powerful way — it’s very destabilizing to heterosexual identity. To be a straight person and discover you’re infertile is almost like discovering you’re not a straight person. Gay sex can only ever make a mess and straight sex makes a life. For us, it was like, Woo-hoo!, we can do this. When I came out 20 years ago to myself, I thought I wouldn’t be able to have kids. But I didn’t really want them then anyway. As I got older, more things became possible. We went ahead and did an adoption because it was the most autonomy we could have as gay men and have a baby. We’re not anti-women. We did an open adoption, which means the birth mother chose us and is involved. She comes for visits. We have a relationship with her. We’re not running from women.

Like many gay men, you first considered having children with lesbians.

But it was really complicated. The lesbians made it clear that they wanted to be the primary parent. Initially, I didn’t want to be the primary parent — I was single, 30 and felt like I was getting really old to have kids because when my parents were my age they already had teenagers. But what I realized in these discussions was that what I wanted was what I was talking to these lesbian couples about making possible for them. I didn’t want to be a glorified babysitter or drop-in dad with no power. I was going to sign papers that said I couldn’t say anything. I had a lawyer friend who said, “That is crazy.” I wanted to be a full-time parent, and during these talks I met my boyfriend.

You took a radical step — you went from point A to point C.

We adopted really early in our relationship. If I had met a gay couple that had initiated the adoption process after being together for two years, I would laugh in their faces and say, “You’re crazy. Gay relationships don’t last.” I hate this kind of talk — it was a beautiful night on the Titanic — but I feel like I’m never going to break up with this guy.

When Terry and I met, I said, “Being with me means you would be a step parent, so you need to know that.” Kids were on the radar from the beginning of our relationship. Two years into it when the kid hadn’t happened, it felt like we were supposed to have kids. So we initiated the adoption process, and that took a year.

You chose an unusual form of adoption. Did you think it would be easier for a gay couple to do an open adoption?

We thought open adoption [as a gay couple] would be much harder. With closed adoptions, the agency chooses the child, and there have been cases, including one in Seattle, where the birth mother found out that a gay couple had adopted the child and sued to get the kid back. We didn’t want to have to live in fear of an accidentally opened file revealing our identity to a birth mother who may have a problem with homosexuality. That also attracted us to open adoption. The birth mother would pick us, and homosexuality wouldn’t come up. But we were equally concerned that no birth mother would pick us. When we went to a two-day seminar at the agency, they brought birth mothers to talk to the couples considering adoption about their decision-making process, who they picked and why. They both said they were looking for Christian homes. We’re both sitting there going hupta-hupta-huh. We believe in a lot of things — we believe in Stephen Sondheim’s inherent genius, we believe in Bette Midler’s world tour, but we don’t believe in the second coming of anything except ourselves.

Our gayness wasn’t an issue for the mother who chose us — in a way that I distrusted at first. The whole issue of adoption for us was that we were gay. One of the things we learned in the process, which I don’t say in the book, was that the only people who had any issue about us being gay men doing an adoption was us. Everyone else was fine.

I think gay people assume that they’re going to encounter [homophobia]. We go into environments with great big pink chips on our shoulders and look for the slight and we find it or infer it. Sometimes it wasn’t intended or even there. It doesn’t mean that every bar in Laramie, Wyo., is a safe place to be a screaming queen. But in more and more places in the first world, it’s not an issue. Unfortunately for gay people, the idea breaks down into slave states and free states, I call it (not to compare our plight to the plight of slaves), but it’s a checkerboard. I really think gay people have to take responsibility for knowing where they live. It’s a beautiful thing to stay in Tulsa, Okla., and try to make it a better place for gay people, but that’s a choice. If you’re going to choose to do that and it’s a struggle, embrace the struggle, be affirmed in the struggle, but don’t complain about it. If what you want is a life where your homosexuality is not an issue, move, as many have done. If I had it in me to live in Carbondale, Ill., and fight the good fight, I would do it. I don’t have it in me. More power to those who do, and I’ll write a check every now and then to their cause.

But a mother found you, and she took you down an unusual path. Melissa, the birth mother, was a “gutter punk,” living on the streets with her pets. The anthropology of disaffected, spare-changing street punks is a major theme in the book.

You see them all over the place, especially San Francisco. These street kids are homeless by choice, employable until they get tattoos all over their faces, but choose to live out on the street with a dog and a backpack. They travel the country, there’s a circuit. And there’s a real community. In the book, I say it’s the Woodstock of this generation, and it really is, it’s just very diffuse and annoying. [Laughs.]

Melissa was a gutter punk — that’s what they’re called in Seattle — and she got pregnant in Seattle. She was living on Broadway, a main street that my boyfriend and I both work on. She probably spare-changed us while she was pregnant, before she realized she was pregnant. She went to the agency because she had a friend who was also on the streets who had a baby that the state then took away from her and put it up for adoption. She picked us, after she was rejected by two other couples. One of them rejected her baby because she had been drinking during the first 4 1/2 months of the pregnancy. We almost rejected Melissa’s baby for the same reasons. But the more we learned about fetal alcohol syndrome, the more of a scam we realized it was.

You hunted for information about FAS on the Internet.

We went on the Web, and you just can’t trust anything you read there! [Starts to laugh.] Even the stuff that’s out there on pulp about fetal alcohol syndrome is written to scare pregnant women away from alcohol. It’s not written to assess the real risks of fetal alcohol syndrome from the occasional glass of wine. Ironically, the only people the FAS literature terrorizes are the women who could be trusted to be responsible and wouldn’t harm the baby. The pamphlets make it sound like if you dip your finger in wine, your baby will be born inside-out.

One of the most difficult moments in the book is when the birth mother turns her baby over to you in the hospital.

Nineteen months later, I can’t talk about it without crying. It has seriously impacted our discussions about adopting again. We would want to do another open adoption, but we’re not sure we could go through that again. We would live in dread of that moment because it was so hard. All three of us suffered, to the ultimate benefit of this baby.

We were really unprepared. No one talked about the moment of transfer, where Melissa signed the papers. We had been in the hospital room a couple of days just hanging out, changing the diapers and feeding the baby — the three of us sharing those first couple of days, which was really important. There came a time when we had to leave the hospital with the baby and Melissa had to go home to an apartment. She put the baby in a diaper and a going-home outfit and buckled him into the car seat — she was ignoring us and the counselor and interacting with the baby. I’m starting to cry. We physically had to pick up the car seat and pull them apart. Melissa, who’s very stoic — not a very emotionally available person — started sobbing. It was really hard on us. I put my hand on her shoulder and said, “You’re going to be a part of this child’s life, you’re going to be its only mother and we’re going to see you.” She still sobbed. When our child grows up, we’ll be able to tell him what she looked like at that moment. And if, God forbid, as a result of the way she lives, she should die before he’s old enough, we’ll know. He won’t have to wait until he’s 20 and go on a biological mother search and find out his mother’s dead and never know what happened. The emotional and logistical problems of open adoption are small potatoes compared to the value that being present at the moment has had for us and is going to have for our son. Seeing what we saw, what kind of monster would it take to deny her contact? It was a moment of absolute blistering pain.

There are inherent risks that come with staying in contact with the birth mother. Melissa is homeless and leads a dangerous life. Do you worry she will put your child at risk?

It’s not really danger. If Melissa or the birth father came and dicked away with the kid, it would be a kidnapping and they would go to jail. They’re not the parents; they’re not the legal guardians; they don’t have custody. It’s fearful from the outside, but knowing them, I don’t fear it. It’s more like they’re relatives of ours, Melissa and Bacchus [D.J.’s biological father].

How much contact do you still have with Melissa?

In an open adoption agreement, you agree to a minimum number of visits — a floor, not a ceiling. It’s enforceable. If we try to deny Melissa her four visits a year, she could take us to court, or she could go to the police. We wouldn’t do it — she can come over as much as she wants whether it’s agreed to or not. She can disappear on us, but we can’t disappear.

She’s a homeless street punk who travels around. She calls us collect, but we’re not home a lot of the time. We frequently get hang-up calls from the AT&T operator, and we go, Oh, Melissa tried to call. We’re relieved when we hear from her. It’s like having a new kind of a relative — my son’s mother, who is not one of my son’s parents. We are related to her through this kid, and we worry about her in the way that I worry about my cousins or my aunts. It’s not an obsessive worry, I just want to know that she’s fine. She lives a very dangerous lifestyle right now. We want her to call us to tell us every once in a while where she is.

You’ve made a lot of sacrifices in your own lifestyle for the sake of parenting — especially some of the perks of urban gay culture. How would you react 10 years down the road if Melissa comes back to visit, high on pot, riding the rails, and your son is old enough to be bothered by it? Will you be open to it, or will it be a problem for you?

We are going to want to do what’s best for the kid. If he’s uncomfortable with or disturbed by his mother, we will help him process that and deal with it in the same way that someone who has sole custody of the child with another parent they have to see. Sometimes those relationships aren’t all beautiful. We still live an urban life. We don’t think gutter punks are bad people, so we’re not going to raise him to believe that people who do drugs or are homeless or want to ride the rails around the country for four years and not have an apartment aren’t good. We’re not going to hardwire emotional conflicts into this kid so that will play out when he meets his mother.

I lived my whole out life on the five-year plan. That as a gay man, I should expect to die, and that I expected to get infected. People who took similar calculated risks to the ones I took got infected and died. I also felt it was disrespectful to the gay men in my life who were going to die to talk about 20 years down the road. One of the things that the Protease moment and end of the AIDS crisis has done for me is allowed me to think about the next 50 years, instead of just the next five. Thinking about the next 10 years, we really think Melissa will be dead if she doesn’t stop what she’s doing. We’ve said that too her. She’s been doing it for three years, and it feels like it’s the only way she knows how to live. We’ve offered to help her if she wants to live some other way, without trying to be prescriptive, without saying, “Why don’t you go to nursing school?”

Calling your book “The Kid” is a lot like calling your column, “Hey, Faggot.” It’s like reclaiming a pejorative.

I wanted to call the book “$238 an ounce,” which is what the baby cost us when you divided the expense of the adoption by his birth weight. It was much more cynical than “the kid.”

One chapter of the book is devoted to your reasons for adopting. Some are noble, some humorous, some downright dubious. You even admit, albeit jokingly, that you expedited the adoption process because you had a book contract but nothing to write about. In a New York Times Magazine special issue on status in America, you also described your son as “my little status symbol.” Do you worry about how he’ll respond to your writing when he’s old enough to read?

He’s going to know me. He’s my kid, he’s going to be around me all the time. I think he’ll be familiar enough with my sense of humor by the time he’s old enough to read this book or 20-year-old New York Times clippings to know that I joke. My whole family is full of nothing-that-is-said in earnestness is taken seriously. The way we say I love you is to say, “I hate you, you suck.” That’s just the way my family is — and the way his family is going to be. I don’t worry about it. I don’t think it’s going to be an issue for me any more than it was an issue for me that my mother would show us her four Cesarean-section scars and say, “Look what you did to me.” There will be no Sam Shepherd moment where I inform him through a lot of tears that I only adopted him because we had a book deal.

We were in the adoption pipeline and I had a book deal and the two were separate and distinct, but I didn’t know what the hell to write a book about. One of the reasons we were going ahead with the adoption was because I had an advance from the book company and that helped pay for the adoption. The book deal made it possible, but the book deal didn’t become about the adoption until after I was already going ahead with it.

As a gay man, to what degree was adoption a political or symbolic act?

I think there’s no such thing as an unselfconscious choice as a gay person in a public place. An adoption is a public place — you have to go to the agency, to courtrooms, you have to let social workers into your house, and as more things become possible for gays and lesbians, we become sometimes more intoxicated by what we can do. We have to be very honest to ourselves about whether we really want to do it or if we’re just doing it because we can.

Do you worry that you might inadvertently endanger your child as a gay father? There was a recent incident in San Diego where a child with a lesbian parent was tear gassed at a gay pride family event. Do you worry that the unintended consequences of your decision to adopt could fall on your child?

Bigotry puts my child at risk, and bigotry is the problem, not that I have a family. We don’t tell black people to have white children to protect them from racism. We don’t tell Jews to bring up their children as Christians to shield them from anti-Semitism. We identify racism and anti-Semitism as the problem. As more gays and lesbians have families, there will be more incidences of children encountering homophobia who aren’t gay. I believe already that our son is straight, just from the way he interacts with women and the way he insists on smashing everything he can get his hands on. I have no doubt he will encounter homophobia, but we will do our best as parents to protect him, as any parent would. We’re not going to send him to a military school any more than a Jewish family would send their children to a fundamentalist Christian homeschool nightmare-a-thon. You can’t protect them from all things.

When he encounters homophobia, that is an opportunity for us to parent. How we help him deal with that is an opportunity to demonstrate that we love him. It will make him more of a family, just as black parents have to parent around racism and how to deal with it.

“Savage Love” is sexually graphic. At what point will you explain to D.J. that you write a weekly sex column? Will you let him read it?

My parents were pretty repressed about sex. We didn’t talk about it much until the mid-’70s when they decided that it was hip for parents to talk about sex, which was horrifying. The repression played out in my adult life by filling me with twists and kinks and perversions that I have enjoyed very much and would regret not having been endowed with. I don’t want to be too open or too healthy about sex with my son because I wouldn’t want to deprive him of an interesting and fulfilling sex life as an adult.

There are families where there’s too much openness about sex. That makes me feel uncomfortable. When kids begin to have an interest in sex, they begin to read about it. I didn’t go to my parents and ask, “May I shoplift Penthouse Forum?” I just went and shoplifted it. I expect that he will do the same, and that he will probably read my column at that point. When he’s old enough to be interested, I think he’s old enough to read my column. Kids are interested in what’s weird. You give ’em the birds and the bees lecture and then they want to hear about the pooh eaters and the cross dressers. It doesn’t make them that, but they want to hear about it. Boys love the gross out stuff, and a lot of my column is for them.

What marks would you give yourself as a dad?

I’m from a very verbal family. I view myself as part of this continuum of crazy parents. I think we’re going to be good parents. It’s not in the book, but before we even considered adoption, I said, “Well, let’s go to a shrink and just talk about this, let’s get a third person there.” One issue we had to work out was that my boyfriend would always say, “If you have sex with someone else I’ll leave you.”

I would say, “If that’s true then I will not adopt a baby with you.” Infidelities happen and it would be unfair to the child if I adopt with a boyfriend who would leave me over something so common. We had this huge conversation with the shrink, who interrupted and said, “You don’t need me here, you’re expressing how you feel and working through this stuff without me here.” I think he’ll do pretty well. We’re people who read. We have a TV, but it’s not on 24 hours a day. We’re chatty, we have a lot of friends. I think we’re good parents.

Adoptive parents can sometimes have difficulty bonding with a child. There were hints in “The Kid” that it wasn’t automatic for you.

It’s great now. I’m totally bonded. In adoption, your parenthood is an act of will and it takes time. You have to perform these parent roles to feel like a parent. My boyfriend is the stay-at-home parent and has been more involved with the baby and still is. I’m on the book tour, he’s home with the baby. It was only natural that I should not feel bonded. I wasn’t prepared to not feel bonded because everyone says adopting is just like having biological children. I took comfort in that they always say to adoptive parents that the person the child calls daddy or mommy is the parent, the person the child regards as the parent. That happened at about a year and it was powerful.

Is it difficult to be away from D.J. so much, with your busy travel and writing schedule?

I wish I could say it was harder than it is. I love being home. I love being with the baby, but I really am a workaholic. I love being at work. I love having a boyfriend who doesn’t have to work right now. I love being in this position where I have this little cash cow column so he can stay home and doesn’t have to work. I feel like 1950s dad, the provider, unexpectedly like my own father, which I’m not always comfortable with.

Would you adopt again?

We want to have two. Children of gay parents should have siblings, to have another person in the house who you can help or can help you deal with problems as they arise. I think children should have siblings, period. We were going to adopt right away, but we decided not to because our baby is a perfect baby. He sleeps, he doesn’t cry, he’s a perfectly mellow and content little person. Terry would want another infant, and he’s an expert manipulator. I’m afraid we’re going to get another real baby and that we’ll smother it because we won’t have the Stepford Baby, we’ll have the regular baby.

Also, we worry that Melissa’s going to get pregnant again. If she does, we would like to be able, if she decides to do another adoption, to offer her the choice of placing the child in the same home, so that the siblings could be together. It would be easier for her to see them. If we adopted again right away it would preclude that because we don’t want more than two children. Out of respect for Melissa, we’ve decided to wait a few years and keep that option open for a reasonable amount of time.