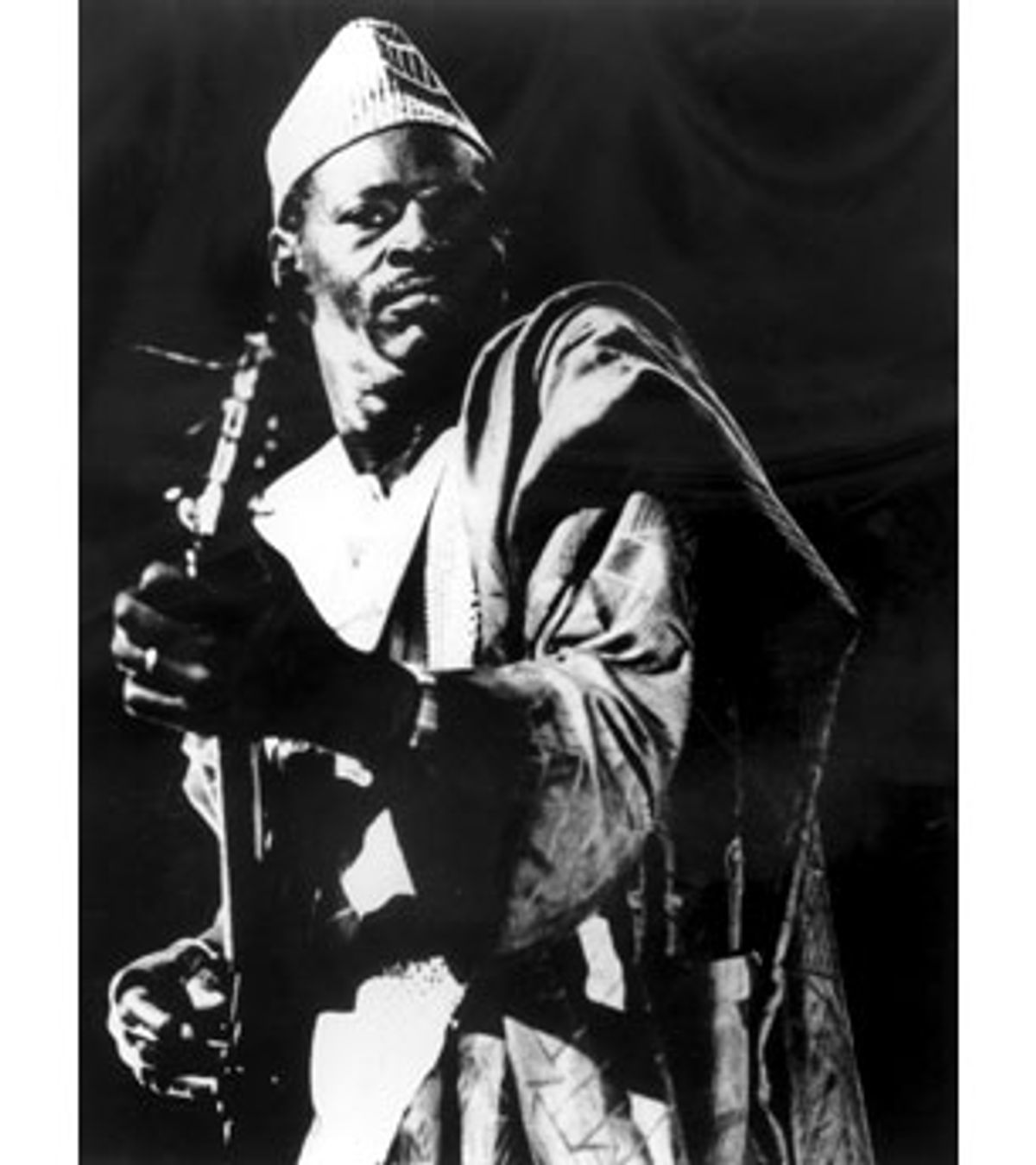

One of Africa's hottest guitarists, Ali Farka Toure -- real name: Ali Ibrahim Toure -- was the 10th child born to his mother, and the first to live. He was nicknamed Farka ("donkey") because he was stubborn enough to survive.

Toure grew up, and still lives, in Niafunke, a village of about 6,000 on the banks of the Niger in Mali. When he was young, he harbored musical ambitions, which were thwarted because neither of his parents belonged to a Griot caste, whose members are historically responsible for Mali's song and dance. But Toure was adamant.

He joined the village's cultural music and dance troupe, rising rapidly to become its director. Along the way, he danced and sang in his native language -- Songhai -- and other dialects and played several instruments, including the single-string guitar and violin. He picked up a Western guitar in 1956, after a chance meeting with Keita Fodeba, director of Guinea's National Ballet. Soon, it became his obsession and during his teens and 20s he transferred his country's music from the traditional instruments to their Western cousin.

Then, in 1968, the same year a friend introduced him to the music of John Lee Hooker, Toure bought a six-string electric guitar while touring in Bulgaria. Toure insists his music grew on its own, but his sound -- a pluck-heavy groove paced with pregnant pauses -- echoes Hooker's, as if a call and response sounded across the Atlantic. Regardless of influence, the association with Hooker's sound helped draw British producer Nick Gold and helped make "Talking Timbuktu," his 1994 album with Ry Cooder, both a Grammy winner and an eight-month top-seller on Billboard's world music charts. And now, that aural brotherhood is confirming Toure's role as Mali's ambassador of music.

Malian music, by the way, while on the road to reaching a global audience, has made a few unfortunate detours.

Two Malian musicians -- guitarist Jalimadi Tounkara and ngoni-player Bassekou Koyate -- were scheduled to record in Havana as part of what became "Buena Vista Social Club," which has sold more than 2 million copies worldwide. Instead, their passports failed to arrive in time, and they and their country's music were left behind, at least temporarily.

But Tounkara and Koyate's missed opportunity is beginning to look more like a postponement than a cancellation. Three months after the widely popular Africa Fete tour brought Malian talent to American shores, Western listeners are slowly discovering Mali's appeal. They have much to discover. Ali Farka Toure has just released a new, richly nuanced album named after his hometown, which is where it was recorded. Meanwhile, American musician Taj Mahal also has a new offering, "Kulanjan," which mixes the blues with the sounds of the kora player Toumani Diabate, among others. And several more Malian artists have recordings in the works. Perhaps no single album will ascend the Everest of "Buena Vista's" popularity, but together these musicians have caught a collective ear.

"There is a broad, general gravitation to this music," says Banning Eyre, author of "In Griot Time: An American Guitarist in Mali," which will be published in April. "Over the past 15 years, a lot of African music has been foisted on the American public, and not much has taken hold. But if you take a look at who is currently signed by major record companies -- Ali Farka Toure, Toumani Diabate, Habib Koite, Salif Keita -- you simply cannot name another African country that has as many artists signed to major American labels. There's a natural selection process that happens, and I think Malian music has risen on its own merits."

Ironically, Toure remains a somewhat reluctant participant. After "Timbuktu," he toured, but quickly tired of the chew-and-spit cycle of Western audiences. According to his friends, Toure grew cynical and longed for home. When he gave up the tour, he turned down the potential for more stardom, not to mention dollars.

"He was developing this irrigation project," Gold says, speaking from the London office of World Circuit Records. "And it's quite a desolate landscape there. Toure is not one to start and not finish a project, so that was important to him because when he isn't there nothing gets done. Also, he started to become disillusioned with the music world. He felt that growing and farming were more important. He said he had lost the desire to play because he was away from the source of his music, away from his inspiration."

Gold had wanted to make another recording with Toure. Instead, two years ago they made a deal: When Toure was ready, Gold would come to him. That day came just before sales of Gold's previous on-site project -- "Buena Vista" -- took off. Gold had tried once before to record Toure on location, but with only a DAT machine, the drums drowned out the guitar and the recordings never made it to market.

On the second attempt, Gold refused to compromise. Along with one other producer, he took a handful of sound engineers and a truck full of equipment. Gold flew first to Mali, a place dominated by desert and semi-desert where few roads are paved. After arriving in Bamako, the capital, he made the 200-mile overland trip to Niafunke with Toure at the wheel. A few rabbits died along the way (Toure stopped to shoot them "for dinner," Gold says), but the equipment survived.

"We took a 24-track mixing facility and a mixing deck," Gold recalls. "And we found an extraordinary place to record -- an abandoned building. It was full of rubble and impossible to use at first. But then they cleared it out, and miraculously, all of our equipment worked. Even after it was banged about."

In that building, a weighty brick structure, Gold recorded the debut album of Afel Bocoum, Toure's guitar protigi. And on the third day, at dusk, as the mosquitoes came out, Ali Farka Toure entered the makeshift studio, plugged in and began to play.

According to Toure, the resulting album, titled "Niafunke," is his best in 30 years. "This music is more real, more authentic," he writes in the liner notes. "It was recorded in the place where the music belongs."

Eight other musicians join Toure on "Niafunke's" 12 tracks, and Gold says he never knew where the guitarist was going, or who he would ask to join in. Usually, the entrances came midsong with only a nod for advance notice. It made an already difficult recording job even more taxing, and in some cases one wishes the songs sounded a bit more crisp, but the new album also has a spontaneity and unpredictable mix of sound. If "Talking Timbuktu" was "Kind of Blue," then "Niafunke" is a more accessible "Bitches Brew." Toure sounds energized, unpredictable, stubborn. In short, "Niafunke" sounds a lot more like the man who made it.

According to Gold, it also captures its setting, both the nature and people who have made the often flood-ridden, difficult land their home.

"One of the facts of recording on location is that people are more relaxed," Gold says. "And you have access to a larger musical community. If you bring people [to a recording studio], you get whoever comes. You have to work with what you've got. But the most exciting thing about going to where the musicians are is that you say, 'OK, we'd like a violin on this song,' and someone says, 'Oh, I'll get one.' That's what happened with 'Buena Vista' and that's what happened in Mali."

That union of sound, story and landscape makes the album unique, says Delhia Allen, a clerk at San Francisco's Virgin Megastore. Allen only bought "Niafunke" after a customer told her how it was recorded. Intrigued, she took his advice to check it out, and after listening to a store copy, she was hooked. Though she is a young black woman, Allen says the idea of buying something African didn't play much of a role in becoming an Ali Farka Toure fan. Simply put, the story sucked her in and the music kept her interested.

"The subtlety of the guitar and the voices, the men and the women, it doesn't beat you over the head," she says. "Plus when you buy a CD, it's often for a single, but with 'Niafunke' the whole CD goes together, and that's something I really like. These days it's hard to find a CD that fits together so organically."

Coming from Banning Eyre or Nick Gold, such comments are commonplace, but Allen is not a veteran of world or African music. When she isn't in college or working, Allen typically listens to Tori Amos and admits to owning only one world-music disc, "but that's a saxophone player who's more Western," she says. Still, Toure has recruited her. In fact, she's become a bit of a Malian evangelist, recommending "Niafunke" to several friends and letting others borrow the disc for a sample taste.

When academics and journalists try to break the code of such fandom, they tend to diminish Allen and others who testify to the magnetism of music and to the power of word-of-mouth. Mali's experience appears to be no different. Kay Shelemay, a professor of music at Harvard, says that the West's interest in all of African music has grown steadily since the first recordings were made in the early part of the century. More recently, political movements -- the American Civil Rights movement, and the era of African independence shortly thereafter -- spurred the trend. And events ranging from the Live Aid concert to Mandela's rise in South Africa, to the widely reported war and famine in Rwanda have kept interest in African culture in the public consciousness, she says.

The political link rings at least partly true. Gold says the audience for Toure and other Malian musicians closely resembles the white, educated, NPR-listening crowd that made an anti-Apartheid act out of buying Paul Simon's "Graceland" or a Ladysmith Black Mambazo album. These are the people who see music as a form of education, and obscurity as a sign of credibility, Delhia Allen says. "I think in some ways, the Afro-Cuban explosion is being bought up by people who use it to have this cultural edge. It sort of says that I am into this kind of music and not a lot of people know about it. It has this cachet. I think it's the same with African music."

But novelty only reaches so far. There are, of course, hundreds of obscure places. What makes Africa and Cuba different, what makes their music so fascinating to Western listeners relates less to novelty than history. Cuba represents Kennedy, the Cold War. Similarly, Africa signifies a past long-repressed: slavery.

Mali's links run even deeper. Though the French colonized Louisiana for only a short time, and Mali until 1960, the two spots share linguistic similarities. The term "gris-gris," for example, corresponds to Louisiana voodoo, is the name of a Dr. John album and also signifies the leather-thonged amulets that some people wear around their neck in Mali as part of their animist tradition. In the past year, Malian style has also become popular, first appearing in the "Star Wars" prequel. Now, mudcloth, a coarse earth-toned fabric, is also appearing in vests and hats of hip, downtown New Yorkers.

But the biggest U.S.-Mali link resides in the music. Toure may have tired of Hooker comparisons, but he recognized their musical bond as soon as he heard the legendary bluesman. "It's 100 percent our music," Toure says, recalling his first experience with Hooker. "The roots are in Africa." Henry Louis Gates Jr., the chair of Harvard's Afro-American studies program, underscored that point in October's PBS series "Wonders of the African World," when he traveled up the Niger river to Timbuktu, stopping in Bamako to groove in the local "juke joints." And Taj Mahal has long expressed a sense of musical oneness with Mali.

Not surprisingly, on his latest recording, Taj plays with Malian kora player Toumani Diabate, a Guinean singer and five other Malian musicians, including Bassekou Koyate, the ngoni player who missed out on "Buena Vista." The collaboration's result is lively, deep and diverse, a mix of Taj-heavy backbeats, quick high-pitched runs, and ethereal vocals. Even without Taj, "Kulanjan" represented a historic chance to unite music from the ancient Manding Empire, with the bluesy danceable sound of southern Mali's Wassoulou music.

Taj only met Diabate in 1990, but they hit it off immediately. Diabate opened Taj's show the night after they met, and the idea of "Kulanjan" was formed. Nine years later, the idea became a reality. And according to Eyre, who was at the clapboard house in Athens, Ga., when "Kulanjan" was recorded, the musicians meshed as if they had been playing together during all those years apart. "It was very, very easy and spontaneous for them to work together," Eyre says. "Most of those songs they put together in a half hour, then recorded them in the first take."

Eyre attributes the easy mixing to a complex relationship between the blues and Malian music, both older traditions that Taj and Diabate have faithfully followed. And to a large extent, that fusion remains possible because, unlike other countries, Mali has remained true to those roots, Eyre says.

"You'll find countries with old people that are worried about children listening to hip-hop," he says. "That's not happening in Mali. Having traveled to a lot of countries in Africa, I can say that Malians are really into their music. It's not comparable to what's going on anywhere else: There are new artists being generated, and old artists are being challenged to generate new work within their tradition."

That exuberance, Eyre expects, will keep people like Allen coming back for more. And the music's relatively newfound audience deserves some of the credit too. Not only have they embraced world music, but they've also learned to discriminate. "Twelve or 13 years ago, people would say, 'I like world music,' then they might say, 'I like African music,' says Gold, who has been recording the globe for more than a decade. "But now they're learning to differentiate."

Eyre agrees, adding that the more people learn, the more Mali's stock will rise. "People will argue about whether Juju is better than South African pop, but Malian music is a given, it's always in their collections," Eyre says. "I believe that anyone who listens to this music will like it." Companies such as Rykodisc, which is distributing "Niafunke" through its Hannibal label here in the United States, are hoping that Eyre is right. They have invested heavily in the work of several Malian musicians.

So far, the lightning has yet to strike. "Kulanjan," also on Rykodisc, is only at No. 11 on the world music charts, and "Niafunke" has sold about 100,000 copies in the U.S. and England. But this might simply be a sign of Cuba's red-hot status, which may fade when the well of "Buena Vista" spin-offs runs dry. Mali could then act as a follow-up, an argument buttressed by the many Malian albums still on the way, at least one of which will feature Toure. Gold says Toure called two weeks ago to invite him for another visit sometime early next year.

Gold is also planning to complete the rain-checked Mali-Cuban collaboration. He says Jalimadi and Bassekou, who he saw in London less than a month ago, are disappointed to have missed out on the "Buena Vista" sensation. But neither is bitter, perhaps rightfully so.

That's a scene Allen would welcome. "I find myself singing along [with 'Niafunke']," she says. "Then I wonder if I'm disrespecting the words. But I can't help it. I like the way it sounds."

Shares