The police presence is everywhere here, but can easily go unnoticed. Along Istiklal Avenue, the heart of Istanbul’s cosmopolitan night life, plainclothes police officers with active walkie-talkies weave through crowds, scrutinizing identity cards for an eastern or southeastern “memleket,” or birthplace, and sometimes take people into custody for unknown reasons.

These arbitrary detentions are in contrast to the otherwise cosmopolitan atmosphere of Turkey’s most European city. In the cafes, waiters serve coffee and beer. Patrons sit on low stools playing backgammon or talking animatedly. At each corner, the simiticis call out “simit, simit, simit,” selling the round pretzel-like pastries that go well with Turkish tea.

But away from Istiklal Avenue, with its plush consulates and carefully tended gardens, are hidden casualties of a fading war in the predominantly Kurdish Southeast that has polarized the country. The 15-year-old conflict has brought to the surface Turkey’s deep-seated problems with ethnicity and freedom of expression. In Istanbul, as in many cities, families evacuated from the war-torn regions of the Southeast are crowded into shanties and other poorly constructed housing. With their previous sustenance based on agriculture and animal husbandry, many migrants face unemployment in the cities, and their children must work instead of going to school, to help make ends meet.

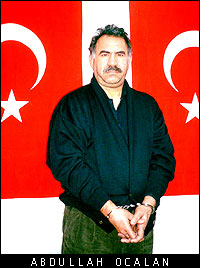

The war has infuriated many Turks and created a tide of intolerance toward the Kurdish minority. For the families of slain Turkish soldiers, no single figure embodies the evil of that war more than Abdullah Ocalan. The controversy over the Kurdish rebel leader’s fate has revealed the most recent threat to Turkey’s efforts at reform.

In mid-January, the Turkish government postponed a parliamentary vote on whether or not to hang Ocalan, its No. 1 enemy. The 51-year-old leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) was convicted of treason last summer for leading the guerrilla war against the state in the country’s predominantly Kurdish Southeast. Ocalan, who remains in prison, called on the guerillas to put down their arms in early August, saying that he wanted to work out a political solution for peace.

The move to delay a vote on the death penalty does not reflect a change of heart about Ocalan. Rather, Turkey knows that its enactment of the death penalty would shut the door to its accession to the European Union, which it has fiercely coveted for years. In December, the country was granted EU candidacy. One of the EU’s requirements for accession is banning capital punishment.

Turkey has had a 16-year de facto moratorium on capital punishment, but popular reaction to Ocalan has vigorously called for lifting it. The state blames Ocalan for the deaths of 30,000 soldiers and civilians in the conflict. Emotions over Ocalan run deep. Following Ocalan’s capture in Nairobi by Turkish intelligence agents last February, TV news outlets showed segment after segment of families of Turkish soldiers demanding “death to the terrorist chieftain.” Small children in school uniforms paraded with posters of Ocalan labeled “blood-sucking baby killer.” Grisly photographs of corpses accompanied still shots of Ocalan in newscasts. His lawyers were physically attacked by a jeering crowd while police looked on.

The controversy over Ocalan’s death sentence is only part of a larger and thornier issue for Turkey’s bid for EU accession: its human rights record. Turkish and international human rights groups have documented arbitrary detentions, torture, disappearances, extra-judicial executions and imprisonment for “thought” or “speech” crimes in Turkey. Many cases relate to the oppression of Kurds.

In a country where the military is revered and every son in every family is conscripted into military service, you are either with the state or you are against it. Such a view is sanctioned by the 1982 constitution, drawn up by the leaders of Turkey’s 1980 military coup. In its preamble, it states, “No protection shall be afforded to thoughts and opinions contrary to Turkish national interests.”

The overwhelming sentiment against Ocalan intensified this attitude and swept to power the far-right National Movement Party (MHP), now part of the three-party coalition government. The party’s now-deceased founder, Alparslan Turkes, admired Hitler and Mussolini and dreamed of a pan-Turkic movement spanning Central Asia.

And despite a fledgling shift toward reform at top levels of the government, the effort has not translated to changes in police conduct, the courts, or at the grass roots. For instance, MHP supporters attacked the Ankara office of the Human Rights Association (IHD) in November because of the organization’s opposition to the death penalty, a spokeswoman for the groups says.

As a result of this us-versus-them mentality, many journalists, activists and intellectuals (both Turkish and Kurdish) have gone to prison for what they’ve said or written. Akin Birdal, the former general secretary of the IHD, went to prison last year to serve a 12-month sentence for “inciting racial hatred.” His sentence stems from a 1996 speech in which he called for “peace and understanding” with respect to “the Kurdish people.”

Turkey has spent years working to harmonize its laws with those of the EU. In order to become economically acceptable to the EU, Turkey is cooperating with an IMF plan geared at ridding the country of its crippling 80 to 90 percent annual inflation. (Labor unions warn that the plan could lead to numerous strikes, as the minimum wage has been set at the equivalent of about $152 a month. In Istanbul, it costs about $67 a month to take one bus to and from work.) Such concessions to the EU have caused the historically jittery Turkish stock exchange to double in the last month.

But the nation’s treatment of the Kurds presents a complex evasion of the EU’s human rights requirements. The EU’s Copenhagen Criteria calls for the “respect and protection of minorities.” But Kurdish identity is not an acknowledged identity in Turkey’s constitution, nor in the Lausanne Treaty signed in 1923. In it, a “minority” is defined as non-Muslim. Since Kurds are predominantly Muslim, they are not accorded any of the rights of a minority. Depending on who you ask, the number of Kurds ranges anywhere from 15 to 25 percent of the country’s population of 65 million.

Clashes between Kurds and Turks are nothing new. Kurdish identity, language and nationalism were officially banned in the 1920s upon the founding of the Turkish Republic. At that time, Kurdish leaders and their followers revolted. In response, the Turkish government set up an independent tribunal in the Southeast that for two years was granted the authority to impose capital punishment.

Ocalan formed the PKK in the 1980s along Marxist-Leninist lines in order to bolster Kurdish identity and to wrest territorial autonomy from the government. Since the beginning of the guerilla war, some 3 million Kurds have been forcibly evacuated from their villages, according to the IHD. The Turkish central government declared martial law in the entire region from 1978 until 1987. Six provinces remain part of the so-called Emergency Rule Region.

Although the state denies it, a suppressed government report by a parliamentary committee that convened in June 1997 reveals that Turkish security forces, as well as the PKK, were responsible for the forced evacuations. The report quotes former Diyarbakir Gov. Dogan Hatipoglu as describing a scene in which “men in uniform” set villages on fire. He added that the evacuations “must have occurred ‘with the knowledge or instructions of security forces or state officials,'” and that no one has investigated whether unauthorized people ordered the evacuations.

Kurdish people have also struggled for cultural survival. Back on Istiklal, the director of the Mesopotamia Cultural Center, Yildiz Gultekin, explains how the police make regular visits and have disrupted the center’s work. It publishes books, calendars and cassettes, and produces films in the Kurdish language.

“Ten people have been arrested here in the last year, and we can’t give performances outside in the Kurdish language,” she says. The government also warned them it would close the center and all its branches if they performed plays in the center’s theater. In December, the state opened a case against it for a calendar it produces in Kurdish. In what many hope will prove to be an official turnaround, Turkish Foreign Minister Ismail Cem recently said, “All people should be allowed to learn and broadcast in their native tongue.”

Change appears to be coming, if slowly. Even before the prospect of EU membership, influential Turkish industrialists spoke out about the need to democratize on issues of diversity and ethnic identity. TUSIAD, an organization of the country’s largest industrialists, recently released a report that calls for lifting cultural prohibitions, abolishing thought crimes and lifting restrictions on language.

Prospects seem to be improving for the Kurds, as well. HADEP, a legal Kurdish party, won four mayoral races last April in the Southeast. These victories came in spite of state lawsuits that threatened to close it down because of suspected links with the PKK, despite the detention of thousands of its members and the raiding of its offices since Ocalan was captured.

HADEP Diyarbakir Mayor Feridan Celik told a Turkish daily that he thinks things have changed for the better. “Everyone thought that the state would remove from office the elected HADEP mayors.” Instead, he said, “The state appointed officials and administrators who could get on well with the local people and not struggle against the local mayors.” The HADEP mayors had an official meeting with Turkey’s President Suleyman Demirel, which was viewed as tacit acceptance of HADEP at the highest level of state.

Similarly, the Turkish government and the Parliament have passed constitutional amendments and legislation that are undoing some of the more draconian laws. Last year in a move to broaden the independence of the judiciary, the state security courts are no longer allowed to have one presiding military judge. In order to curb abuses by security forces, a provision that allowed them liberal use of firearms was canceled. Law now prohibits virginity tests, which had routinely been administered to women in detention or entering prison.

In its bid for EU accession, there are indeed positive signs that Turkey is moving forward. But whether or not its reforms and changes will be put into practice on all levels — from government to police to increased rights of its citizens — remains to be seen.