On their glorious new album, “And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside-Out,” Yo La Tengo free-associate dub, folk, electronica, experimental rock and vaguely jazzlike phrasing into a 77-minute document of stylized style mining. The group’s every utterance, however, is instantly recognizable. After 13 years of making music together, the trio — who call both Hoboken, N.J., and Brooklyn, N.Y., home — musically wink at one another like old friends acknowledging thoughts already well understood.

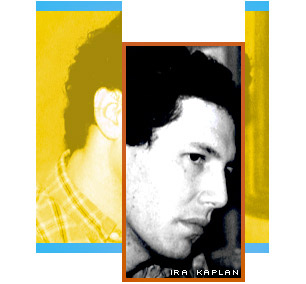

It’s a sustained conversation that hears subtlety as giddy screams — and one that helps the new album sound both exactly like and not at all related to any Yo La Tengo record before it. The familiar reference points are all there: Ira Kaplan’s guitar dramas, Georgia Hubley’s finessed drumming, James McNew’s loudly understated bass, the trio’s shared wistful vocals. But cast in a newly consistent atmosphere — all lazy dusks and distant, cotton-pulled cloud masses — they articulate more than the band has ever attempted to translate.

Typically reserved in his own quiet, quasi-unassuming way, Kaplan shared the following thoughts. His words are either microscopic cracks in the record’s code or reasons to look to it for answers offering real resolution. He spoke over the phone, cozy at home while Hubley, his wife, flipped through records to prepare for the night’s coming DJ set at an album-release party.

This new record has a stately air that separates it from the group’s older albums. Is that something you’ve seen happening as you’ve moved on from drawing a mostly cult audience?

Yo La Tengo Saturday 28 | 64 Let’s Save Tony Orlando’s House 28 | 64 You Can Have It All 28 | 64 RealMedia(Don’t have the |

We’re not oblivious to what’s going on around us, so if we get a well-positioned review in Rolling Stone, it’s hard not to think about that. But I wouldn’t say we think about it very much at all. When we were making the record we didn’t have any idea what the response would be. We could make a case for people who’ve been interested in the band being disappointed by it or being intrigued by it. But that kind of conjecture doesn’t ever seem to lead to very positive results.

Does it seem to you as if the notion of indie rock has grown out of its own self-willed marginalization, that the wall separating a small community and a larger audience has crumbled a bit?

I don’t know that I fully agree with that. There are still plenty of people who are perfectly happy to maintain that wall, or a sort of distance like that. But [as] for our band, we’ve always gone on the road, done interviews, done things to try to get our music in front of people. Our last record [“I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One”] sold a lot more than our earlier ones. Bands like Pavement made lots of commercial inroads that changed those perceptions. And just being around for a certain length of time changes the way people approach a band. But I’ve always found it odd when people have ever referred to us as lo-fi. That’s always been mind-boggling because we’ve been in 24-track recording studios for all these records. I think people have wanted to think of us as being in our bedroom making records and just never emerging.

Do you hear anything on the charts you find interesting in any way?

I am completely 100 percent oblivious to whatever is on the charts. I spend 10 seconds a week looking at the Top 10 in the Monday business section of the New York Times. That’s my only connection. But I guess I hear that stuff when I go to basketball games. That’s where I first heard [Chumbawamba’s] “Tubthumping.”

You are a big Knicks fan. Does that make you a Bill Bradley man?

[Laughs] I’m sorry to say it does. It’s embarrassing but true. When the New Jersey primary rolls around, I may just have to cast my ballot for the ’69 Knicks. It’s nice to be a part of the electorate making that choice for horrible reasons: “I like the way you used to move without the ball … I think you’d make a great president.”

You’re also a big baseball fan — Mets rather than Yankees, right?

Yes. Unlike in basketball, where I have only good feelings for the Nets and wish them well — except when they play the Knicks — I’m the classic baseball fan. I like one team to dislike the other. I just really don’t like the Yankees’ owner, and since he wants to be synonymous with his team, I’m going to let him. [George] Steinbrenner reminds me of [Rudolph] Giuliani. He’s just a bully.

You go to a lot of downtown jazz shows in New York, and you’ve sort of tapped into that scene recently. [Percussion phenom Susie Ibarra plays on the new album; Yo La Tengo recently released a double 7-inch recorded with members of jazz act Other Dimensions in Music.] Has that mostly improvisational music influenced your approach to the band?

I would imagine it has. I always think that is happening with whatever we’re listening to. It’s hard for me to compare record to record because they’re from such different times and the memories are so different. But it doesn’t feel like that aspect is so entirely different. The songs are written based in improvisation at the start, and we try to leave songs unfinished so we can make spur-of-the-moment decisions in the studio. My feeling is the difference with this record affects the way people hear it almost as much as our approach to it. Because the new songs are more stylistically similar, I think you notice all the little arrangement touches; it almost calls attention to them because they are the differences in these songs a lot of times. Before, you could say there’s a fast one, there’s a slow one, there’s the one Georgia sings. There were ways to describe the songs using much broader terms, but now a lot of the differences are in the details.

A lot of those details’ roots seem to come from electronic music too. How has that vocabulary affected your songwriting?

It’s interesting to me how little of that is on the record and all the attention it’s gotten. The songs are mostly generated by all the same instruments we’ve played in the past. Kevin Shields [of My Bloody Valentine] did a remix for us from our last record, and when we would play it live we would try to imitate his mix. In a way, that’s what we’ve continued to do. Most of the impact is in us trying to imitate some of the beats and some of the feel — at least as it registers to us — using the instruments that we play. And it did have some impact on the mixing of the record. We were particularly more open to different kinds of effects than we have been in the past. But I’m not really too clear on the definitions of electronic music. It’s kind of intimidating with all its substrata.

The cover of your new record is a Gregory Crewsdon photograph that shares a similar sense of atmosphere with the music — quietly surreal, innocent but suspicious, etc. [The photo shows a boy in a suburban setting staring skyward at a mysterious light source — maybe a spotlight, maybe a Martian ray beam — it’s not entirely clear.] Crewsdon has a show in New York right now. How did you hook up with him?

We’ve known him casually for many years. In a way it sort of reminds me slightly of working with some of the jazz people we talked about. In the last year, we’ve really tried to expand our sphere of who we work with, like people other than friends in bands that we know in other ways. Georgia has usually done our record covers, but with Gregory we liked the idea of bringing somebody else into it. It still has a personal element that we liked, but it’s also very different for us. Throughout the selection process we got increasingly brave in using a more arresting image. I think in a lot of the things we do, we err on the side of restraint. But in using somebody’s images that are so strong, we were warming up to idea of using something like that.

Was it weird to see Georgia and yourself in the New York Times Magazine as the perfect picture of bohemian wedded bliss? A lot of the new songs are direct love songs between you two, but has all the attention your marriage is getting surprised you at all?

Well, we weren’t really freaked out by the magazine. They never made any pretense of it being anything else. That was understood as the way we were shoehorning our way into the Times Magazine. And no, I didn’t see the attention coming at all. Now, in hindsight, I kind of wonder why I didn’t. But as I was saying before, we really try to remain oblivious to that stuff, and we’re kind of good at it. I don’t seek it out, but I don’t ignore it either.

You’ve said some songs are pure autobiography and others are less rooted in reality. Do you and Georgia talk about your songs to each other?

When we’re writing them we definitely do. This is a group, and even if I write the lyrics for a song, they are still going out with a group’s name on them. I wouldn’t do that without all of us reading them and thinking about them and talking about them. That goes for James as well as Georgia.

One song on the album is called “The Crying of Lot G.” Are you a [Thomas] Pynchon fan?

It is a reference, but maybe not exactly out of my fandom. Lot G is an inside joke to like six people we know, a reference to the Newark Airport. We tried to restrain our tendency to lay inside jokes all over our record this time. We were largely successful, but maybe not in this case.

What about a message in the liner notes: “When in Nashville, visit Prince’s Hot Chicken Shack”?

We spend a lot of time there when we’re recording in Nashville. It’s certainly not fast food; don’t go there unless you have lots of time. And it’s, um, not like anything else we’ve ever eaten, which is the highest praise we could ever give.