Can you pity a writer who’s won a MacArthur fellowship, the coveted, so-called genius award that bestows both confirmation of one’s bona fide egghead status and a financial package opulent enough to keep the genius juices flowing for a handful of years? The annual list of fellows makes for satisfyingly grandiose fantasies, but people also expect the award to be given to writers whose work is incomprehensible and dull.

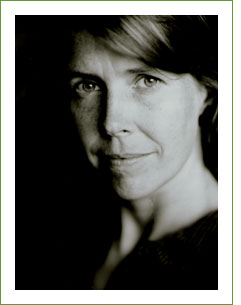

This would be a wholly inaccurate assumption in the case of novelist Joanna Scott, former MacArthur fellow as well as Pulitzer Prize and PEN-Faulkner award nominee; the lofty critical affirmations of the literary establishment have little to do with the actual experience of reading one of her books. Scott is undeniably smart, but it’s not her learned brain that rises full and glowing as Humpty Dumpty out of her fiction; it is instead her startlingly perceptive, fecund and appealing imagination that is the biggest thing about Scott.

In all of her six books, each wildly different from the others, Scott has a lapidary’s instinct: She turns each story over as she would a raw gem, revealing its underside, magnifying every possible angle. Her multifaceted fictions gleam with real-world precision, so detailed that whatever universe she composes — a 19th century slave ship, a rural estate in 1920s New York, artist Egon Schiele’s fin-de-siecle Vienna, the interior landscape of a 4-year-old boy, a blind beekeeper’s orchard — appears solidly dimensional in the mind of the reader, quickened by a powerful narrative force.

But it isn’t just Scott’s settings that are believable. She’s a double threat: a writer who has the breadth of imagination to detail even the most minute sensory qualities of her fictional setups, and who also specializes in shaping and dissecting characters who come across as quirkily and mysteriously human. Human behavior, with all its vagaries, its shadows and light, is her project, and her characters, no matter how peculiar or obsessed, are drawn with a compassionate and relentless curiosity. Scott writes of her beekeeper, the protagonist in a story from the 1994 collection “Various Antidotes”: “With remarkable accuracy he could imagine the experiences of others … he comprehended these in rich particularity. Perhaps empathy rather than imagination would better describe this skill.” The same is true of Scott.

Scott’s preoccupation with the spiritual development of individuals has grown more evident with each of her books. Her first novel, “Fading, My Parmacheene Belle,” chronicles a furious flight by two haunted souls, one a 15-year-old runaway, the other an old fisherman whose ranting, book-long soliloquy is his tortured reconciliation to widowhood after 53 years of puzzling married life. The gruesome, wind-stalled journey of the slave ship in “The Closest Possible Union,” Scott’s second book, is also a metaphor for the moral journey of the novel’s young narrator, a 14-year-old who is both the captain’s apprentice and the son of the ship’s owner.

In the prismatic “Arrogance,” a fictionalized life of the Austrian expressionist painter Schiele, Scott creates a fragmentary structure informed by the artist’s tormented self-portraits and scandalous career, thereby shaping a meditation on artistic genius, psychic struggle and societal imprisonment. The widely praised “Various Antidotes,” arguably Scott’s best-known work, explores the theme of scientific passion from the perspectives of characters whose obsessions drive them to grim extremes — ranging from Charlotte Corday, who stabbed the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat in his bathtub, to the Dutch inventor of an early microscope, who kisses his daughter “not like a father should kiss a daughter but like the devil kisses” in order to steal a tear and test his new invention.

In “The Manikin,” Scott gave full rein to her natural gift for the strange and eccentric. A full-blown Gothic mystery, “The Manikin” is set in a rich taxidermist’s gloomy, isolated mansion where each of the stranded characters is symbolically trapped in time, their lives as suspended as those of the stuffed creatures that line the halls. What links this novel to her latest, the newly published “Make Believe,” and what sets both books apart from her earlier inventions, is a sustained authorial voice.

The novel opens with Bo, a 3-year-old boy and the pivot about whom the plot of “Make Believe” turns, hanging upside down from his seat belt following the car accident that has just killed his teenage mother, Jenny. Bo is now an orphan — his gifted, teenage father, Kamon Gilbert, was shot and left to die on a sidewalk, a random act of violence that occurred two months before Bo’s birth. After emergency surgery for a damaged spleen, Bo goes home with Kamon’s parents, Erma and Sam Gilbert.

Bereaved over the death of their son but content to raise their grandson, who has been in their daily care since Jenny started a job, Erma and Sam see it as pure and simple chance when an ordinary day closes with food on the table and their family’s good company instead of ending with tragedy. Similarly, Bo’s parents had attributed to the randomness of chance — it was neither good nor bad — the fact that Jenny was white and Kamon black.

Jenny’s stepfather, Eddie, however, saw Jenny’s pregnancy and her black boyfriend as evidence of her intrinsic corruption and drove her out of the house where she grew up. It is when Jenny’s passive mother, Marge, receives a huge bill for Bo’s emergency surgery, a bill for the care of a grandchild she has never bothered to meet, that Scott’s plot begins to take its full shape. The story’s linchpin is Eddie, whose inflexible belief in his moral superiority — and greedy desire for a spiritual test of his righteousness, conveniently dangling before him in the guise of a medical malpractice suit on behalf of Bo — stirs him to press for the custody of a child for whom he has previously shown complete scorn.

Rather than the skittish, untrustworthy narrators or limited viewpoints of her earlier works, in “Make Believe,” as in “The Manikin,” we experience Scott’s entire imagined vista through her own omniscient eyes. The scope of the world is described from the bottom of an ice-covered lake in midwinter — its shifting light, its iron-colored water gelatinous with cold. It is also described from the viewpoint of Kamon, as he lies bleeding on a sidewalk after being fatally shot, his dying, stream-of-consciousness moments growing equally more hallucinatory, essential and dimmed as they tick past. And it is seen from the vantage of a monumental discovery in the consciousness of Bo as he first savors the “bitter pleasure of pity.” Sent to his room in punishment for a misdeed, “he cried just thinking about himself crying, a sorry sight that would evoke, in memory, enough self-pity to sustain him for a lifetime.”

For a writer focused on the illumination of the subjective, imperfect, mystifying human journey, choosing a small child as a protagonist can be an exciting challenge, a method by which to expand and contract the boundaries of how a story can unwrap itself. It can also be a dangerous gamble capable of stalling a novel with an unplayable hand. Scott has played it safe by teaming her unveiling of Bo’s inner landscape with the points of view of his parents and grandparents, thus creating a palette of personality and perspective from which to choose when coloring in the details of her narrative.

Bo’s fantastic, partial and instinctive understanding of his world is at once wholly innocent of and stimulated by the desires of the many adults who steer his fate — and whose individual worldviews are likewise shaped by fantasy, partiality, bitter experience and instinctively camouflaged motivations. In Bo’s estimation, Eddie, the stranger with whom he finds himself inexplicably living, “always looked like he wanted to be doing something different from whatever he was doing.” When he catches a glimpse of his dead mother’s face in grandmother Marge, Bo suddenly thinks himself “the victim of some terrible lie, having long ago been told a story about the whereabouts of his real mama and for all this time believing it to be the complete, undeniable truth.”

Bo’s are the simple and often poignant truths of childhood. After the car accident, the hospital personnel conclude that Bo’s shock at his mother’s death has made him mute. In fact, Bo is sticking strictly to his mother’s rule — Never talk to strangers! — for fear that his mother will be so angry she’ll never return if he does speak. Scott reveals her sensitive instinct for childhood wisdom throughout her handling of Bo’s character: His sense of himself in the world is both inflated and confused. He has a child’s uncanny radar for friends and enemies, for appropriate adaptation and for self-inflicted harm. Bo reminds us, also, that our perception of time’s unfolding evolves so noticeably as we age and yet never really changes: A toy sheriff’s star is lost and “There is only now, luckless empty now.” Moments later a toy is found, and Bo is jubilant, his good fortune returned, “his head pounding with the colorful blur of the here and now.”

Scott captures each of the novel’s primary characters with equal precision and subtlety. She trusts in her own sensitive meter for human perversity and mood shift to further inform their personalities — a trick often hard to pull off in fiction without confusing readers about the “true” nature of the players. Benumbed Marge, for instance, who has spent decades allowing Eddie to dictate her every decision and thought, finds secret pleasure in accusing her upstanding husband of sleazy behavior and watching him spin furiously with indignation, even after she recognizes that he is innocent of that particular brand of wrongdoing. Kamon is finely drawn as a talented, responsible man-child packed with all of the conflicting emotions and urges of late adolescence: arrogance, amazement, sloppiness — reciting lines from Shakespeare one minute and smugly taking advantage of his cousin’s stupidity and laziness the next. Then there’s Eddie: Well, Eddie is the kind of person who gives humorless, Bible-thumping stepfathers a bad name.

Yet with all of its vividness and flashes of insight, “Make Believe” has some serious problems, all of which can be traced to rickety plotting and the attempt to mask it. Because Scott chose not to include the custody hearing in the book, Bo’s removal from the Gilberts hangs on a book the widowed judge read: “The novel irritated him, and his irritation made possible an irritating acceptance of the significance of matrilineage.”

That seems believable in itself, since it’s not hard to imagine that a family court judge’s decision could be swayed by such unconscious forces. But considered alongside the novel’s other crudely outlined coincidences — a cousin just happens to have been arrested for drug possession on the Gilberts’ front lawn making their home seem an unsavory environment for a child; the haziness of the medical malpractice situation itself; and the hospital informants who appear without warning to grease the wheels of litigation — Bo’s appearance in the home of Marge and Eddie ends up feeling forced.

And what of the Gilberts? Bo’s paternal grandparents are passionate enough about Bo that they make an abortive attempt to flee with him, and yet they seem to never take a legal stand by asking to raise their adored grandson; instead, they relinquish him without so much as a peep. Scott drops hints that their passivity is based on a conviction that the white grandparents will invariably win any courtroom struggle, but race is such a nonissue in this novel (except, perhaps, to Eddie) that the hinting itself feels disingenuous. Disingenuous, too, is the feel of some of the dialogue. Scott is typically dead-on in creating voices for her characters, but here the dialogue often feels stilted, forced or coy: Even the characters don’t seem to believe what they’re given to say.

With “Make Believe,” it seems almost as if Scott has stretched for herself too small a canvas; you can feel her (in her long, evocative lists of free-floating daily awareness, or in her focused monographs on the minutiae of costume, food and habit) breaking out of the story at its edges.

With these reservations noted, the sheer force of Scott’s storytelling impulse coupled with the depth of her characters sustains her novel, and her readers, to its conclusion. In a fateful moment late in the story, when Bo has escaped out onto the disintegrating ice of the lake and a devastated Marge flees her complacency and her husband in order to save the little boy, her plaintive, sincere plea to Bo to “please believe me” reverberates in the heart of the reader. “Please believe me” — it carries with it all of the desire, disappointment, hope and hopelessness that flood our own unanswerable prayers. It reminds us that this is still a Joanna Scott novel. We feel then, at the book’s ending, a bit like Bo — happy to be there, though vaguely confused. While it is not her strongest book, with “Make Believe” Scott still convinces her readers that they could do a lot worse than to spend a few hours inside her mind. She can and does make you believe.