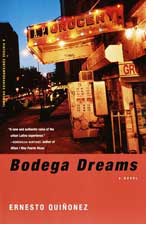

“It was always about Bodega and nobody else but Bodega,” Chino, the narrator, says at the beginning of “Bodega Dreams,” Ernesto Quiqonez’s fast-paced uptown noir. That’s Willie Bodega he’s talking about — former Young Lord, later a drug kingpin and Latino visionary, an “unforgettable blend of nobility and street, as if God never made up his mind whether to have Bodega be born a leader or a hood.”

Bodega’s dreams lie at the center of Quiqonez’s story, and the action revolves around Bodega’s dangerous trajectory. “Willie Bodega didn’t just change me and Blanca’s life, but the entire landscape of the neighborhood,” Chino realizes. But, his words to the contrary, it’s not just about Bodega. An even more vibrant, thrilling character looms over all the others: Spanish Harlem itself. It is this neighborhood, its history and geography, that propels Quiqonez’s pulsing, cinematic narrative (and, yes, the film is already in production).

|

But then again, in a sense Bodega represents Spanish Harlem. He dreams of owning its buildings and uplifting its people even while financing his plans for an East Harlem “Great Society” with filthy drug money. “Bodega was a lost relic from a time when all things seemed possible. When young people cared about social change. He had somehow brought that hope to my time,” Chino thinks. He is cautiously impressed at first: Bodega is busy restoring apartments and sending kids to college to become the future foot soldiers in his war on Latino poverty.

There’ll be a hitch in these grand schemes, however (beyond the cops and a rival mobster from the Lower East Side), and that, naturally, will involve a woman: Vera, an old flame from Bodega’s radical days. Fortunately, the backdrop of Spanish Harlem keeps Quiqonez’s story from becoming stock and keeps the action poppin’ and the characters snappin’ — on one another, on Latino pride and dreams and on the Man, who keeps those dreams on ice. There’s Sapo, Chino’s childhood pana, or homeboy, who becomes Bodega’s strong-arm man (with a penchant for taking dog-size bites out of his victims). And Blanca, Chino’s holy and sanctified wife, and her trash-talking sister, Negra. And Nene, Bodega’s slow-witted bodyguard, who speaks in song lyrics. (“Come on people, now smile on your brother,” he hums at one point when things get a little tense between Bodega and Chino.) And Bodega’s frontman and partner in crime, the slick and mighty lawyer Nazario, who knows that “a single lawyer can steal more money than a hundred men with guns.”

Quiqonez is at his freshest evoking the Young Lords, the International Museum of Salsa (which opened in a bodega on 116th Street) and the old Italian turf of East Harlem on Pleasant Avenue. Spanish Harlem infuses the novel with history and adds a political edge; it gives this dark tale heart and redeems it with rooftop reveries and New World hopes. Bodega tells Chino in a dream:

What we just heard was a poem, Chino. It’s a beautiful new language. Don’t you see what’s happening? A new language means a new race. Spanglish is the future. It’s a new language being born out of the ashes of two cultures clashing with each other.

And speaking of poets, many of the luminaries of Puerto Rican — or, rather, Nuyorican — lit make walk-on appearances: Pedro Pietri, Miguel Algarin, Miguel Piqero and Piri Thomas, among others.

Quiqonez’s tale is feisty and hard-hitting (the chapters are called “rounds”); the characters are vivid, sharp-mouthed and wiseass. But the soft soul of the novel is in the ‘hood, and in what it means to Chino, for example, to gaze on it while returning from a meeting with a Queens mobster:

It was getting dark and the Fifty-ninth Street Bridge loomed ahead. Manhattan at night seen from its surrounding bridges is Oz, it’s Camelot or Eldorado, full of color and magic. What those skyscrapers and lights don’t let on is that hidden away lies Spanish Harlem, a slum that has been handed down from immigrant to immigrant, like used clothing worn and reworn, stitched and restitched by different ethnic groups who continue to pass it on.

Here’s an edgy, streetwise first novel wrapped in the magnificent and tattered hand-me-down cloth of dreams that remains Spanish Harlem.