I started nude art modeling while pregnant at the age of 26.

Three months from giving birth, I had attended an art opening and noticed a cluster of tiny pen-and-ink nudes. I wanted a picture of me, too. I approached the local artist, who eagerly invited me to sit. In her cozy home studio, she introduced me to the art of modeling.

My husband moved out 10 years later. I had dated him since high school. We had gone to college together, opened and managed a bookstore together, raised our daughter together. When he left, it was as though he had taken all the mirrors in the house with him. I started to pose regularly for art classes. I thought that the indisputable black lines of the students would prove my existence: I am drawn, therefore I am.

Even today, with my divorce and identity crisis well behind me, I continue to model occasionally for schools and art groups. I think of it as an exercise in self-awareness. Besides, it’s my way to participate in the making of art.

I don’t bring up this activity of mine around my relatives. Only my younger sister, who worked in art restoration for a while, will ask about my modeling. Although my writing about modeling interests them, my family, like most, is rather squeamish when it comes to the subject of public nudity. Knowing that my nudity takes place in the context of art doesn’t make them any more comfortable with hearing the details of my profession.

Caitlin, my teenage daughter, says that she has never felt embarrassed by my posing. She likes to hear my stories after I return from a stint. But Jeff, my beau since 1993, is troubled by my modeling. He has discussed with artists what they think about when they sketch a model, and he even took a figure-drawing class to try to understand what I do.

After almost 20 years of modeling, I expect to be able to anticipate how people will react to my vocation, but I am often caught off guard.

In August 1998, Caitlin needed to have her senior picture taken. Rather than go to the local photography studio, we decided to have her picture taken by John Shimon and Julie Lindemann, two art photographers who work out of their home studio in Manitowoc, Wis., a small town 90 miles north of Milwaukee.

John and Julie specialize in the use of antique cameras, like their 700-pound mahogany Deardorff from the 1940s. They carefully select cameras and lighting to make black-and-white images that are simultaneously direct and dreamy.

Caitlin and I traveled to Manitowoc with a larger agenda than creating a senior photo that would stand out. We also wanted to have Julie and John take some mother/daughter portraits to mark Caitlin’s 18th birthday. A few days before we left, I had the idea of taking some pictures in which Caitlin would have her clothes on and I would have my clothes off. A nude of me drawn the night before Caitlin’s birth always hangs in a place of honor wherever I’ve lived since; I envisioned a “matching” portrait of Caitlin entering adulthood with me, sans clothes, as an important reminder of her entrance into the world. I discussed my idea with Caitlin, John and Julie and we agreed to try it.

I considered informing Jeff about our tentative plan before I left for Manitowoc. We were a committed couple and anticipated living together after Caitlin left for school the following August. As a rule, I’d always tell Jeff where and when I’d be modeling the day before a session. Sometimes he’d give an unconcerned shrug, sometimes he’d commend me for engaging in a misunderstood profession and sometimes he’d demand that I explain to him once again why I found it necessary to continue my modeling.

I decided not to tell this time. After all, I rationalized, Manitowoc wasn’t a typical modeling session. I would be nude in a private setting; it would be modeling as a private act. And I kidded myself that we might not even have the time and desire to experiment with my idea.

Of course we did.

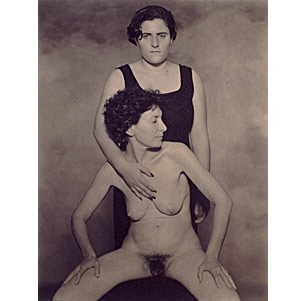

About three hours into the session, we came to the last pose. I told John and Julie I wanted a picture with my clavicles showing. Julie carried over a stool for me to sit on, and I brought my arms forward so the long bones between my neck and shoulders would jut out. Julie suggested that Caitlin change into her formal outfit, a sleeveless, floor-length black dress. After a few minutes, Caitlin returned and stood behind me.

Julie directed Caitlin to swing her right arm in front of me, to show off her long nails. “Maybe it should look almost like you are ready to clutch her heart,” Julie prompted.

We all collaborated. Julie asked Caitlin to look straight into the camera lens. I wanted to tilt my head back and look up, but John and Julie had me try some other positions. After some debate, they voted to have my head turned to the side. John moved the lights around, checked his light meter and closed the shutter. Julie slid in the 11-by-14-inch film holder and stepped back. Julie and John didn’t say anything to let us know when they’d take the picture. This waiting made Caitlin and me concentrate even more. No one blinked. Julie squeezed the air release. The session was over.

Caitlin and I changed into shorts and carried our clothes back to the car. We both felt exhilarated. “Can we come back and do it again next week?” Caitlin begged, only half-kidding. Julie promised the proofs would arrive at our door the next Friday. We wondered how we would manage to wait seven days.

A week later, I was nervously ripping open a large envelope from John and Julie, with Caitlin perched beside me on the living room couch. I pulled out a clear plastic bag protecting six sets of prints. We looked at the pictures in the order they had been taken. We liked a number of the senior photos, especially a partial profile that gave Caitlin the staunch authority of a Roman bust. Then we looked through all the shots of us together in various attire. We made tentative decisions about which ones we would send with my annual holiday letter.

Finally, we looked at the clothed/unclothed portraits. We both gravitated to the last one. I held it up. In the exact middle of the portrait, my clavicles and Caitlin’s hand, so graceful with her elegant nails, meet. Caitlin’s fingers, covering my heart, seem to lay claim to my body. I can trace the faint stretch marks visible on my belly. My oblique profile accentuates Caitlin’s unflinching stare. Although I sit in front of Caitlin, she seems to come forward while I recede. To me, the portrait chronicles the changing orbit of mothers and their emancipated children.

Inside the mailer, John and Julie had enclosed a letter asking permission to make a platinum print of this final picture to include in a retrospective show that would cover a decade of their photographs. If we consented, they would give us our own copy of the platinum print.

There was no question: Caitlin and I wanted to give our consent. We imagined the odd sensation of attending the opening in Madison, Wis., and standing beside our portrait. The photograph documents the comfort that Caitlin and I have with each other, both physically and emotionally. To us, having the photograph included in the show offered the opportunity to exhibit this intimacy publicly.

But having the portrait on public display also meant allowing our private relationship to be open to public interpretation. Although we perceive our close tie as healthy and untainted by pathology, some people might see the photograph differently. They might criticize the portrait as unwholesome — even disgusting. But Caitlin and I would interpret that response as saying something about the viewer. We’d slough it off.

I was concerned, however, about Jeff’s reactions, and those of my parents, who lived nearby. Although the retrospective would take place in Madison, more than an hour’s drive away, Milwaukee papers often review the Madison art scene and friends of theirs might read about the photograph or see the exhibit. If someone Jeff knew saw the picture — like his daughter who lived in Madison — and expressed disgust to him, he wouldn’t be able to toss the comment aside.

I dreaded telling Jeff about the upcoming exhibit. We’d already had one argument after I disclosed that I’d been nude for some of the mother/daughter portraits. He had blasted me with questions: “Why do you always have to push the envelope? What did Caitlin think?” He insinuated there must be something wrong with me — as a mother and as a person. If he was this upset about a photograph intended for our private viewing, he would certainly not take kindly to the idea of the same photograph in a public space.

Jeff had seen plenty of pictures of me on art school walls, but never in a gallery. And there’s something about a photograph: It’s one thing to have me captured in charcoal or paint on a wall, quite another to have me displayed in a full frontal photograph, with no soft shading or muffled pigment to cover me. The pose itself, with Caitlin and me together, increases the exposed quality of the image.

After I had considered all the elements — the heightened medium of photography, the graphic nature of the pose and the fact that it would be displayed in a public gallery — I reluctantly offered Jeff the prerogative to keep the photograph out of the show. Caitlin was disappointed by my decision, though she said she understood my reasons.

Jeff wasn’t my only worry. I also had to consider how my mother and father would react. My mother goes to art museums all the time. She has read my writing about art modeling; she has seen drawings of me nude. But she has never seen what I do. Earlier in the summer, she had turned down an invitation to watch me model. This photograph was a work of art. Maybe it would be just the thing to help her push beyond her uneasiness about nudity; maybe she would celebrate a photograph of her daughter and granddaughter being displayed at the Wisconsin Academy of Art.

My mother happened to be visiting on the day that John and Julie delivered — in person — our copy of the platinum print. I was struck by how the embedded quality of the platinum print reinforced the drama of the portrait. In platinum, the image seems to soak into the paper rather than lie on top of it. I appear to sink into Caitlin.

When she saw the print, my mother didn’t comment. Nothing.

I called her the next day to gauge her reaction.

“Mom, how do you feel about John and Julie including the photograph of Caitlin and me in their show?” I asked.

“I’d rather they didn’t,” she replied curtly. “I’m worried the picture will come back to haunt someone.” She said that she was worried about protests from political conservatives. After some prompting, she confessed that she was more worried about her own friends seeing — or hearing about — the photograph.

“Well, you could just say, ‘I think it’s a wonderful picture,'” I suggested.

“Yes. Yes I could. But your father will not be happy about this.”

A few days later, when I brought up the portrait during another phone conversation, she said that she didn’t believe she had a right to keep the picture out of the exhibit.

By this time, Jeff had also mulled over the situation. He had finally come to the conclusion that my happiness and my creative freedom outweighed his own anxiety.

Subject closed. I had won a shallow, begrudging victory. I hadn’t advanced my cause to have Jeff and Mom applaud my modeling as soul-enhancing performance art, but I hadn’t lost any ground, either.

I went upstairs and pulled out the platinum print. Was having the image in the retrospective worth potentially humiliating my parents? Was it worth putting Jeff and me through an emotional wringer? I propped up the picture on my bed and looked at it.

Yes, it was.

As it turned out, Caitlin and I couldn’t make it to the Madison opening, but Jeff surprised me by proposing we make the 80-mile drive to Madison to see the show together. The photograph was placed in the middle of three mother/daughter portraits. Jeff noticed how in all three portraits the adolescent daughters stare straight into the camera lens, while the mothers look askance. He got so excited that he called to see if his daughter was around so she could come and see the pictures, too. I hadn’t won Jeff over. Art had.