Keith Gordon’s “Waking the Dead” is a smart, romantic drama with so many ideas playing at once that it sometimes can’t work through all of them. It’s a film about passion and power, compromises and culpability, and the way that love can make logic seem irrelevant. It’s also about political ambition and social responsibility, about gestures meaningful and meaningless, about devastating loss and the mind tricks that the dead play on the living.

At center, the movie is a love story about happy opposites Fielding Pierce (Billy Crudup) and Sarah Williams (Jennifer Connelly). When they meet in 1972, Fielding is a Harvard grad doing a stint with the Coast Guard. Sarah works for a groovy, socially conscious book publisher who happens to be Fielding’s hang-loose brother (Paul Hipp). Immediately, she’s worried that Fielding may be drafted for Vietnam. He tells her, seriously, that he wants to be president of the United States, and that he needs to wear a uniform. She tells him that she wants “a life that makes sense.”

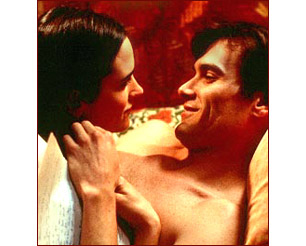

The two move to Chicago. He studies law. She works at a Catholic charity. Their conflict is simple. They both want to do good in the world, but she believes that a corrupt system corrupts absolutely. He believes that it’s impossible to be effective outside the system. They’re clearly in love. The on-screen chemistry between Crudup and Connelly is sparkly without a phony glitter, and Gordon has a tasteful way of shooting the love scenes that makes the two seem sexy and passionate without groping like drunken teenagers or romance novel parodies. After finishing law school, Fielding falls in with a political king maker (Hal Holbrook) and the district attorney’s office. Meanwhile, Sarah gets caught up with activists working with Chilean refugees.

The film, based on Scott Spencer’s 1986 novel of the same name, cuts back and forth between the early 1970s and the early 1980s. At the start, Fielding learns from a television newscast that Sarah has died in a car bombing with the Chilean activists. The film then flashes back to when they first met, developing the love story, and then forward to the cold, sterile ’80s, centering on Fielding and his first major political race.

While campaigning for a seat in the House of Representatives, Fielding has a crisis of conscience and begins to see visions of Sarah. As the stress of the campaign mounts, and as he navigates some potentially ruthless political sharks, Fielding becomes consumed by his memories of Sarah. The film plays with a magic realism that makes her as alive as Fielding thinks she is, while never fully committing to his state of dementia.

When “Waking the Dead” is at its best, it tells a very honest love story and asks moral questions that don’t seem extremely popular. (One of its messages seems to be that there actually was a time in recent American history when unchecked capitalism wasn’t a universal morality.) When the movie slips, it shorthands some dramatic action and relies on rote images to signify simple meanings. (A scene with an impatient governor gulping scotch and waiting for Fielding to make a major career decision feels forced and portentously obvious.) And, at least once, near the ending, the film spells out what the book’s author trusts the reader will figure out on his own.

Director Keith Gordon, who made the excellent war film “A Midnight Clear” (1992) and “Mother Night” (1996), fell in love with the book at the same time he was falling in love in real life. He also adapted the screenplay, even though another writer appears in the credits. (Although Gordon never saw the other writer’s screenplay, Writers Guild bylaws demand in certain cases that the first writer always retain credit.) When Gordon talks about the film, he, well, rambles a bit. When I spoke with him recently, he talked rapidly, in long, erratic sentences, as if his language couldn’t keep up with the ideas running through his head.

It was a press day event in an Upper East Side New York hotel room. Gordon sat at a large, round table crowded with wires, microphones and a half-dozen radio reporters. (Oddly enough, Salon was included in this group.) Gordon was accommodating and articulate. Even though Salon is responsible for only a few of the questions below, we nevertheless thought the interview was worth running in full, rather than stripping for a few choice quotes.

You’ve pointed out that there are different ways of looking at this story. What is the story you tried to tell?

There were two things simultaneously. First was the idea of loss, and really dealing with loss in a story. [When I read the book] I was in the midst of falling in love with a woman who is now my wife, imagining what would happen if I ever lost her, and how devastated I would be, and whether I could go on, and whether what I had gotten with her would be enough to go on or whether there would be no point. And having those questions come up really got to me.

And I also liked the idea that the book kind of dealt with the complexities of love and how hard it is, and how infuriating it can be, to be in love with someone, and that the very things that you fall in love with about someone are the very things that can push you away from them: What attracts you to someone often makes you want to kill them. And at least those two experiences really spoke to my relationships and hadn’t been done a lot in films.

Do you think it’s possible that soul mates with opposing moral and political ideology can remain together forever?

I guess it’s possible. I think it would be widely challenging, but I think it depends on how those ideologies differ. I think there are situations where it could work, but with these two people … I don’t think that there’s any way these two people could stay together. Everything was literally pulling them apart. Here, you’ve got two people who can’t even exist on the same plane. Her whole point is that you cannot be within the system and still have a soul. And he feels like you can’t go outside the system and be effective. So, these two people can’t, but I’m sure there are people who have found ways to be fairly far apart. There’s just some critical point — God knows where that is.

How did you go about casting, because so much of this film relies on the performances, their chemistry together?

Billy was cast first. We knew that character would be the linchpin. I didn’t really know his work coming into it. I had heard his reputation, but I had moved out to L.A. and had missed his New York theater work. To me, with a character like this, it’s beyond just being about talent. It’s about an ability to work in a very free-flowing way. I knew that with that relationship, and all of the emotions that he was going to go through, that we needed somebody great. The near nervous breakdowns — I wouldn’t ask somebody in an audition to pull that off, but I needed to see that there was going to be that bravery of spirit. And that’s what I got from spending some time with Billy. He had that sense of adventure.

Once we had Billy, it became the Scarlet O’Hara wars trying to cast the woman. No one seemed to get it. We read every hot young actress and every non-hot young actress, and nobody seemed to get the gestalt of it. People would come in and they would get the intelligence, but not have the sensuality. Or they would get the sensuality, but wouldn’t have the anger. They would have a piece of Sarah.

The chemistry between Billy and Jennifer was there immediately. But she also, as a person, brought those other qualities. She had the intelligence: She was talking to me about Chilean literature. And she has a very natural sexuality and sensuality that isn’t pushed. A lot of the actresses from this generation have a sexuality that says [breathy voice], “Hi, I’m sexy,” because they are working at it. Whereas with Jennifer, it was just there, which to me is really Sarah, and very much that era, that hippie chick, natural, “I’m sexy because I just am.”

Did any of your own ’70s and ’80s experiences mirror the movie?

Well, I was so young in the ’70s. Basically, Sarah was the girl who I was in love with as a kid. I was born in ’61, so I was 8, 9, 10, 11 during this time period. And those were the girls that I would look at and say, “One day, I wanna be with a woman like that, somebody who is passionate, committed, sexy, independent.” They were the ones that I always looked up at. So I think it brought back that kind of romanticism.

And then the ’80s were a time that I was coming into adulthood, and I felt very cynical about that. I grew up in the ’60s as a kid, with parents who were very political. I couldn’t wait until I was grown up. And then by the time of the ’80s, it was a time of political conservatism, a time of even more … it was the “me generation.” Both of those spoke not necessarily to my own experiences, but to the colors of those times. I like stories about the recent past. I don’t feel like movies do enough of those that often. But I always think that they’re a great way to explain how we got to where we are. I find myself very attracted to those stories, films like “The Ice Storm.”

The title is what it is, but are you concerned that just a few months ago Scorsese’s picture …

“Bringing Out the Dead?” Well, it certainly was an issue. And if we had come out in the fall, we would have had to change the title. It doesn’t concern me that much. It is the title of a novel and I wasn’t going to start changing it. We started doing that as an exercise and everything that we came up with was pathetic.

Do you have an example?

There was “Waking Sarah,” and “Echoes of Life” and everything sounded like a soap opera. Nothing seemed right. There was something about the levels of “Waking the Dead.” Waking the dead of heart, waking the dead of society — it just worked on all the right levels.

As you often do to excellent effect, moving back and forth in time, did you ever consider using a visual cue other than subtitles to indicate the date?

I wanted to be a bit more subtle. And we did do visual cues, but it was subtle — you might not notice until the second or third time. The ’80s are much colder in color. Everything is blue, the lighting is all shifted to cold and blue colors, the camera is very constipated, nothing is moving much, with formal framing and kind of uncomfortable. Whereas the ’70s is a lot more handheld and flowing, with Steadicam, and the colors are a lot more warm, yellow and orange. But it probably wasn’t going to be enough to clue people in.

Can you talk about the decision you made in your adaptation with the ending. For instance, I felt like the film was very faithful to the book, and at the ending it seemed to sort of split a little bit.

It wasn’t my intention to split from the book. The book ends really very similarly in terms of the letters. The only thing that is different is the monologue, only because the abruptness of ending with the letters — in a literary format, I think that worked. In the film, it would have felt like you hit a wall. And so I tried, to the best of my ability, to write something that I thought was poetically summing up and coming to a conclusion without ever giving an answer. My intent was certainly not to do something different, as opposed to making it work within the world of what film is. But I didn’t want to change the meaning at all.

I’m interested in the way the movie talks about selling out ethically, as opposed to selling out financially. Selling out ethically seems to be a question that was very prevalent in the ’70s, when this was taking place, but it seems to be a question that has largely disappeared. Were you consciously trying to bring that up?

Well, it’s certainly one of the things that attracted me to the material. And certainly it bothers me how little the question of selling out ethically exists anymore. Getting people to think about what it means to be part of the system, what you give up, what you give up not being part of the system — I think those are very good questions. I don’t have answers. Then again, I don’t have answers for anything. But, yeah, I would love people to sort of contemplate that more. Right now, being part of the system is what everybody wants to do. People don’t stop to think, “What am I giving up?”

Do you still find new questions in the film every time you see it?

I’ve probably seen the film 150 times now. In the editing process we really played a lot. I edited much longer on this film than I have ever done before because of the structure. We tried a lot of ways of constructing it. And that would lead to very different questions and different focuses: Now it is becoming more about the politics and now it is more like a love story — trying to find those balances.

But I find that even now, what does seem to be at the core does shift. And it shifts with an audience too. Seeing it at Sundance with different size audiences and different kinds of audiences it would shift. There are times that I definitely feel that people are plugged into the emotional love story. And there are times when I feel like audiences are much more plugged into the moral questions of the film. I feel that there is just a vibe that goes on in a room. And if they do a Q&A afterward, what really changes. I feel like I see different aspects of it. There are not many new questions at this point, but maybe in five years I’ll probably see a whole new film again.