The intensive care unit of Phoenix Children’s Hospital is a remarkably cheerful place, considering the sadness it sees each day. The rooms are decorated by local college students with construction paper cutouts that herald the upcoming season. Today the theme is Valentine’s Day hearts and cupids, with X’s and O’s scrawled across them in crayon.

I am here to visit Thomas, who will be 1 year old on Saturday. The steel bars in his crib are decorated with bright helium balloons, and the crib is crowded with stuffed teddy bears, rabbits and Teletubbies, all gifts from his foster family.

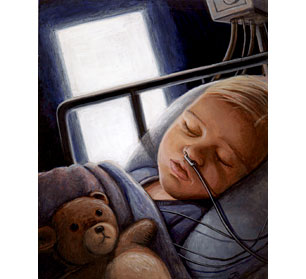

Thomas is asleep now, sedated, because he had been awake and crying for nearly 24 hours. He cries constantly when he’s awake because his pain is so severe. His internal organs were, as his doctors phrased it, lacerated. The medical report says that the injuries to his abdomen are the kind that usually come from being kicked or punched, or from being in a violent car crash. His skull was fractured, and he suffered a brain injury that left him blind. He was legally dead for a while, but the doctors brought him back. When his parents first learned the extent of his injuries, they decided to take him off life support. He lived.

Thomas has been in and out of the hospital since then. The doctors have said that he will not survive, that each of his systems will begin to fail, one by one, and ultimately he will die. He’s back in the hospital today because his kidneys failed last weekend.

I happen to arrive when his parents are visiting, along with the parent aide they are required to bring as a chaperone. I have never met them, and they are confused when I try to explain who I am. I am Thomas’ court-appointed special advocate, charged with reporting on his needs and his best interests. Thomas also has a guardian ad litem (GAL), an attorney who handles his legal interests. And he has a Child Protective Services caseworker and a host of doctors: a pediatrician, a nephrologist, a neurologist, an ophthalmologist, a retinologist and an internist.

Thomas’ mother and father crowd one side of the crib and I stand on the other side with the parent aide. I watch them and try to read their minds. There are no criminal charges yet in this case, as a result of what I can only describe as a stunning quagmire of police bureaucracy. The case has been bounced back and forth between the homicide and the family violence units because Thomas has been dead, then alive, then expected to die soon. Because the investigation is ongoing, I can’t get any information on its status.

The parents offered a story that the doctors have said does not fit Thomas’ injuries. But establishing the real story and collecting the necessary evidence are, apparently, complicated and time-consuming. Also, it’s not clear who abused Thomas, though his parents are the obvious suspects. There were other people in the home when the ambulance arrived. So while ordinarily, with injuries this severe, there would be an order prohibiting the parents from seeing their child, there isn’t one for Thomas.

His parents are leaning over him, stroking his face, touching his legs, examining the tubes snaking around him that are attached to now-permanent holes in his body: a feeding tube in his stomach, an I.V. in his arm and some other tube coming out of his foot. His mother is blinking fast, in that way you do when you’re trying not to cry. His father is murmuring: “Thomas, my big boy. You’re getting so handsome, little man. You have to get better so you can come home. I love you, baby.”

The nurse pulls me aside and tells me again that we really need a DNR on Thomas; a DNR is a do-not-resuscitate order, which is signed by the legal guardian. In this case, the legal guardian is the state. A DNR would mean that if Thomas’ heart stopped, or he stopped breathing, his caretakers would be prohibited from intervening to bring him back. Today, Thomas is “full code,” which means that if he started to die, the hospital would have to use every intervention possible to keep him alive, including long-term life support.

The nurses have previously told me that once a foster child is on life support, the courts will not remove it. I think this has something to do with pro-life issues and the state’s not wanting to be accused of letting a child die, but nobody has told me that.

Thomas’ doctors agree that he needs a DNR. His foster mother agrees. His caseworker agrees. His GAL agrees. I agree. Thomas will never recover, never return to health, never experience anything but constant pain or sedation.

The ironic twist in this case is the parents. They have court-appointed lawyers now, who have explained to them that if Thomas dies, they could be charged with murder. Thomas dying would mean not only that their first and only son was dead but that they each might spend 25 years to life in prison. They will fight the court in granting the DNR. They could win.

I let this thought sink in as the nurse is talking. I watch Thomas. His arms and legs are turned in, malformed because the muscles have deteriorated. He breathes heavily, with a gurgling noise, because of the mucus collecting in his throat. His face is relaxed for a minute, and then he winces in his sleep, makes a scritchy whining noise and shifts his body. The nurse is watching him now too. “This — what you see — this is his life,” she says to me.

A month later, I am visiting Thomas at his home, with his foster family. His foster mother chats with me as she tends to Thomas. He receives 13 different medicines in the course of a day, has shots twice a week to increase his blood platelets and has his blood drawn once a week. He receives four different therapies weekly, from therapists who visit the home.

His foster mother gives him breathing treatments. She thumps on his back with a small rubber tool meant to loosen the mucus in his lungs. She shoves a catheter down his throat to suction mucus out of his lungs. She flushes and cleans his feeding tube, and pushes the little button back into his stomach when it falls out. (This entails plugging the hole with her finger so stomach gases won’t leak out.) She massages him to improve circulation to his skin, which peels off like a lizard’s because of his kidney failure.

She tells me she has called a friend who is a foster mother to dying children. She wanted to know what it’s like when a foster child dies in her home and there is no DNR. The other foster mother explained to her that even if he’s dead, she’ll have to perform CPR until the paramedics show up. She’ll need to have his paperwork and medical records handy because they’ll want them, and she shouldn’t clean him or anything else up because the police will arrive to investigate. She also told her not to expect to be invited to the funeral — the most painful information she acquired during that phone call.

She picks Thomas up, and he curls into her like a newborn would. She sings to him softly and he is quiet. His eyes move and look normal for a moment, and he appears to be gazing around the room. Then he shifts and his breath seems caught; his arms and legs stiffen, he shudders and he begins to wail, a droning whine. His face squeezes to a wince.

Together we imagine what he was like before the abuse. When Thomas was first admitted to the hospital, his skull fracture had already started to heal, so nobody knows for how many weeks or months he was being abused before his family called 911.

But we imagine anyway that he was OK until the August day he received the injuries that brought him to the hospital. He would have been about 6 months old — a chubby, black-haired baby who giggled and flirted and chattered with quiet clucks and high-pitched squeals. He would have had a fuzzy sleeper and teething rings. He would have laughed at peekaboo, and might have liked applesauce and puried carrots.

If not for the abuse, today he would be crawling, surely — maybe walking. Maybe he would like Barney and “Sesame Street,” “Teletubbies” and Elmo. Maybe he would clap his hands and play with stacking cups and a tiny xylophone. He would be well.

I ask his foster mother what she wishes for Thomas. “Sometimes I think there could be a miracle,” she says. “It’s so hard to believe that he won’t get better, but I know he won’t. But you want to believe that he will, you know? It’s hard to hear when the doctors say there’s no hope.”

But when he goes, I ask? How will you stand it? If you’re not invited to the funeral? If you can’t say goodbye?

“Well, he’s a fighter, so I think he’s going to hold on for a while. He’s come back so many times already. But when he goes, I want him to go peacefully. I want him to be comfortable.”

I am preparing for court, writing a report about Thomas, documenting our visits, what his doctors say, my perceptions of the people involved in the case. I am also making recommendations to the court about what it should do and why.

I look back through my notes and discover that I have no picture of Thomas. Pictures are important for foster kids so that they have a record of their chaotic and scattered lives in different households with different parents. For Thomas, a picture is important for another reason. I want the judge to see him — not for the drama of how bad he looks but to see that he’s real, to identify that this is a baby and to have that picture in his head while he reads my report.

I am praying that the judge will be merciful, that he will see the reasons to grant the DNR and that he will spot and judge harshly the self-interest that led the parents to fight it.

The Child Protective Services lawyer tells me not to worry — the judge will surely grant this DNR. Even with the parents fighting it, I ask? Well, that complicates it, of course, she says. How often does the juvenile court grant a DNR? Hmm … well, it hasn’t come up that often in my cases; I don’t know.

So I continue to stack my deck, filling my report with all of the reasons, all of the documentation, all of the letters from doctors who agree with me, and I make a mental note to get that picture of Thomas.

His parents’ fighting the DNR seems like the pragmatic thing to do, given the possible repercussions for them. But it also seems like the ultimate act of selfishness, and even though they have denied committing the abuse, this level of selfishness makes me believe that they did it, or at least knew about it. Because of them, Thomas’ abuse could be never-ending.

He could live forever in pain, in a vegetative state, growing bigger without growing up, suffering through countless surgeries, medicines, doctors, therapies and tubes shoved into him.

He also is being abused by the system, in the same way a rape victim is. He is forced to relive the original atrocity at least for the rest of his natural life, but possibly longer, because the court may allow his life to continue beyond its natural limits, even though he is suffering, and even though the only thing of which he is cognizant is pain.

I have no answers, and nothing I do will guarantee that the judge will grant the DNR. No positive outcomes are possible in this case. A baby is dying, and the question we’re fighting over is when and how. I can only hope that when he is ready to go, he is able to go, and that this happens on his terms. I hope that for this one final act of his short life, he is in control.