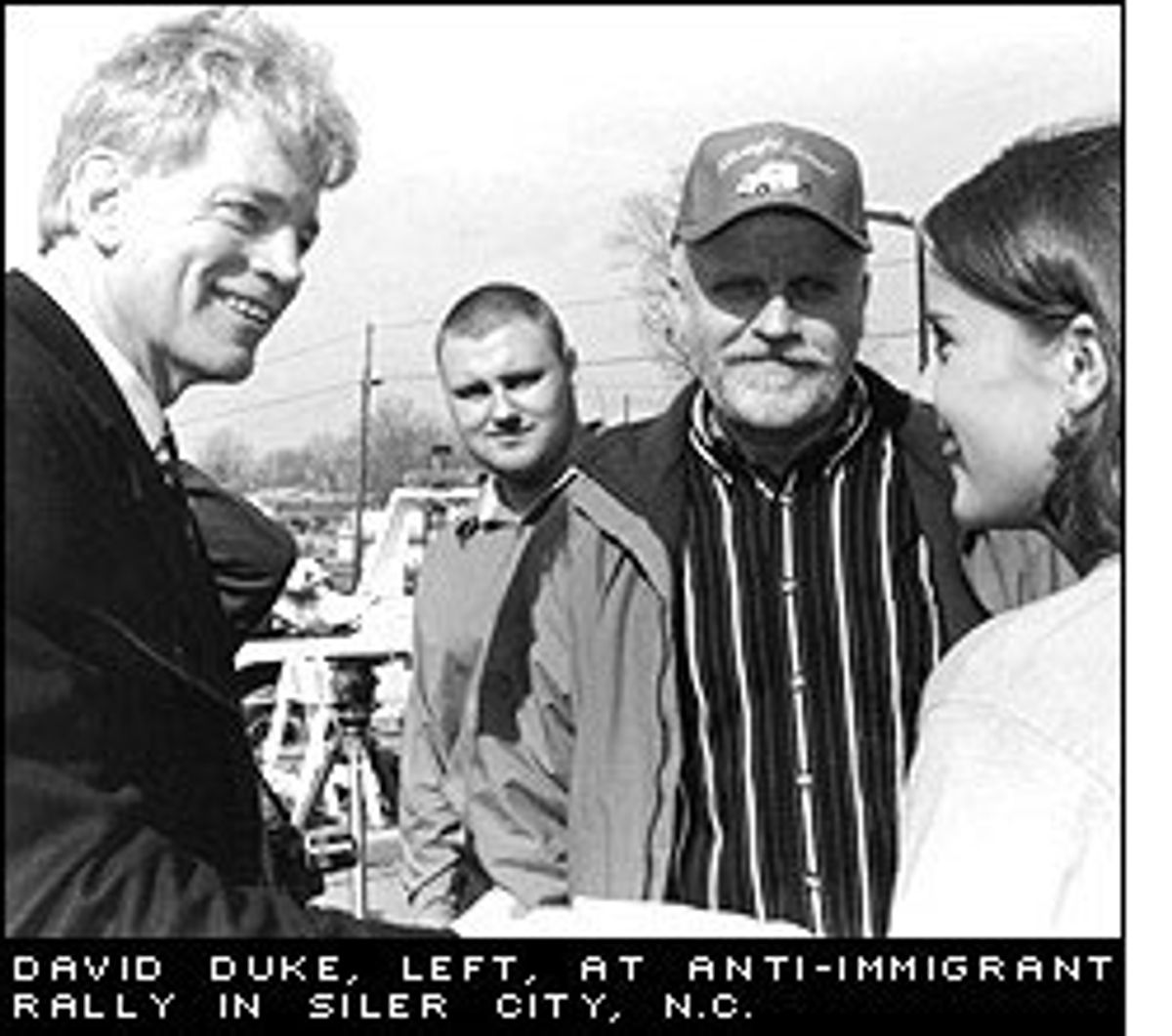

"What you lookin' at?" The words caught me off guard. I was looking at David Duke, former Republican Louisiana state representative and onetime grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. Duke was huddled with his supporters in the Golden Corral restaurant in Siler City, N.C., a small town an hour from Raleigh. The words came from one of Duke's skinhead minions. I ignored him and watched his leader get up with white plate in hand and stroll toward the buffet bar.

Thirty minutes earlier, Duke and his allies had stood in front of City Hall in what can only be described as a Klan rally without the hoods. But instead of attacking African-Americans, this time Duke's forces had targeted Siler City's growing Hispanic immigrant community.

"What's going on in this country is a few companies are hiring illegal aliens and not American citizens because they can save a few bucks," Duke shouted before a crowd of 400 -- roughly 300 supporters and another hundred spectators -- in this rural town of 6,000, where poultry is the main industry. "I guess they need someone to pluck the chickens but it's not just the chickens that are getting plucked."

Duke didn't organize the rally. Richard Vanderford, a local man who sports a vanity plate that reads "Aryan," put it together.

"I'm mad because there ain't no Greyhound buses here to load 'em up and send them back where they come from, every goddamn one of them," said Dwight Jordan, who has been living in Siler City for "41 damn years."

The mid-February rally was the latest, and most explosive, outburst of local frustration over the growing number of Hispanic immigrant workers and their families, who may now outnumber the white population. Thousands of Latinos have moved to Siler City and most work for two poultry processing plants.

Last August, the local county commissioners wrote to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service asking for help in deporting undocumented workers. Hundreds of white parents, and some blacks, have packed school board meetings to protest the new immigrant children's effect on classrooms and all-important test scores. And the Sunday after the rally, the Hispanic congregation at St. Julia's Catholic Church in Siler City arrived to find the church's sign had been selectively defaced and smashed. Only the side that was written in Spanish had been vandalized. The English side had been left alone.

The clashes show the changing dynamics of race relations in the so-called new South. In many Southern towns, Latinos are experiencing resentment once reserved for blacks. African-Americans are caught in the middle, some of them worried about what demographic change is doing to the region, especially its schools. But others are coming to the defense of their new Latino neighbors, especially now that Duke has jumped into the fray, and some black ministers are planning a counter-rally here this month to show Duke that hate won't find a home in Siler City.

The town's changing demographics are directly attributable to the poultry industry. Nationwide, chicken consumption is at an all-time high, the per capita rate rising from 49 pounds in 1980 to 73 pounds in 1998, according to the National Chicken Council. Worker turnover is high in the industry and plants are always looking for replacements. In the past, companies offered incentives to recruit workers or even bused them in. The undocumented status of many workers makes them a pliable and disposable labor force if they get injured or start to organize.

Juan Jimenez, 46, spent 10 years picking tomatoes in Florida before moving to Siler City five years ago to work at a chicken plant. He works in the de-bone area where workers stand all day cutting chickens. "We're doing 18 pollos per minute," Jimenez said. The work is hard, cold and debilitating. Jimenez has been cutting chickens for four years and makes $7.40 an hour. This year he got a 10-cent raise.

Despite the hardship and exploitation, families like his are helping to revitalize a once-dying town. Home values are up because of the influx of Hispanics. Three years ago, a two-bedroom, one-bath house in Siler City sold for $39,000, according to Dowd and Harris Realty, the largest real estate company in Siler City. Today, that same house would sell for $59,000.

Wal-Mart is building a superstore in Siler City, which will heavily rely on the buying power of Latinos. Jimenez, who owns his house, has big dreams for his three daughters. "I want them to go to school to learn something so that when they're bigger they work at something different and not at the [factory]."

But like so many Southern racial clashes in history, the roots of anti-immigrant prejudice can be found in the schools. Siler City Elementary has been most affected by the influx of Hispanic children. White and black parents are afraid their children are not receiving a quality education because many of the Hispanic children do not speak English. This fear sparked an angry school board meeting last September, attended by more than 100 people, that was a first step toward the February rally.

"We're on the outskirts of Siler City and it's not affecting our daughter yet, but we know what it's doing to this school in town and we're scared it's coming our way," said Barbara Hilliard, who was one of the supporters of the Duke rally.

What Hilliard and others fear is a predominantly Hispanic school. Siler City Elementary is more than 40 percent Hispanic and the kindergarten class is more than 50 percent. Parents have complained that too much time is spent helping Hispanic children who lack English skills, known in educational jargon as Limited English Proficient (LEP) students.

Chatham County, where Siler City is located, saw its LEP population increase from 80 students in 1990 to 458 in 1998. There are more than 6,000 students in the system. And nearby poultry counties' LEP populations have more than doubled, from 3,994 students in 1993 to 9,316 in 1997. In fact, poultry counties like Chatham make up almost a third of the entire state's LEP population of more than 30,000 students.

Last August, the school failed to meet its all-important state testing requirements, under a statewide school and teacher accountability program that rewards schools that meet their testing goals with $1,500 teacher bonuses. Teachers at Siler City Elementary received no such bonus. White parents blamed the low scores on the Hispanic children, whose scores are below white children's but generally above those of African-Americans, according to the Chatham County Schools.

So whites are fleeing the school to more predominantly white schools nearby, and the white flight is making it even tougher for the school to do well on the standardized tests.

These issues boiled over at a September school board meeting attended by more than 100 parents -- white, black and brown. No one thought to bring translators for the non-English speaking parents. Many Latinos sat in stunned silence as white and some black parents blasted them and their children. "I know there's a language barrier but that doesn't mean my little girl is retarded or a slow learner," said Virginia Tabor, a Latina parent.

Siler City Elementary used to be a great school, said Kay Staley, a grandmother whose grandchildren transferred this year. "Now it's suffering and it's because of the problem with Hispanics." She offered a solution. "Maybe they need their alternative schools until they learn English and then we'd be glad to have them come to this school system. We paid for this school, it's from our taxes, not from the Hispanics'."

"I don't have a problem with the Mexicans or the whites or nobody," said Annette Jordan, an African-American parent. "But I do have a problem when my daughter comes home from school and says the teacher didn't have time to teach me or show me how to do my homework because she had to take up all her time to teach those Mexicans because they don't understand." Jordan said if she had her way she would pull her daughter from the school, too.

Teachers at the schools pleaded with the school board to end the district's open transfer policy and stop the white flight. "The bottom line is they've allowed for these transfers which has taken away a lot of our white population," said Becky Lane, who's been a first-grade teacher at the school for more than 20 years.

The school board took a hard line with the transfer policy. "I don't think changing the transfer policy is going to make those white parents that are scared to death to have their kid be the only white kid in the classroom stay," said Susan Helmer, a school board member.

But there are signs that the divisions could eventually be healed. Last fall, Rick Givens, the chairman of the county commissioners, was the man responsible for the commissioners' sending a letter to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service asking for help in deporting undocumented workers. The letter complained that "more and more of our resources are being siphoned from other pressing needs so that we can provide assistance to immigrants who have little or no possessions."

The letter was like gasoline on a fire. Hispanics feared they would be deported and pulled their children from schools. The letter seemed to legitimize the townsfolk's anti-immigrant feelings.

"We just wanted to send a message to let them know we're going to start looking," said Givens, a retired airline pilot.

But then Givens and 25 state and local officials went to Mexico for a weeklong fact-finding trip sponsored by the North Carolina Center for International Understanding, a program of the University of North Carolina. Givens felt humbled by the experience and changed his position.

"I still say illegal is illegal, but I found out it wasn't just a simple black-and-white issue," he said, promising to concentrate less on immigration law enforcement and more on "how we can work with the people that are here to help integrate them to our way of living."

The turning point for Givens came when his group visited a ramshackle school 30 minutes from Puebla. There he met a crippled student who desperately wanted to continue his education but could not afford to. Givens pledged to help pay for his schooling on the spot and donated $500. He is also donating 1,000 books for another school's library.

At the February rally, Duke denounced Givens as a turncoat, and supporters brandished signs asking for the recall of "the traitor Rick Givens."

Meanwhile, some African-Americans, many of whom worked in the chicken plants and have since moved on to better jobs, decided they wanted to support the Latinos but had no way to reach out to them.

"I found it so hard to put my hands on someone in that community, even with the clergy, to say, 'This is Rev. Thompson, what's going on?'" said Rev. Brian Thompson, Union Grove AME Zion church. "I think we're just so separated at this point and are foreign to each other that there isn't enough communication." Thompson is organizing a rally to combat growing anti-Latino sentiment.

Duke did not gain a lot of new local support at the February rally. The crowd's attention wandered when his speech traveled beyond the sphere of Chatham County to places like Israel.

After the rally, I asked Duke why it was held in front of City Hall and not in front of one of the chicken plants. He flippantly replied, "Maybe we'll head there next."

But they didn't. They headed to the Golden Corral, to have a lunch meeting and celebrate further dividing the town. I showed up, and watched as Duke walked back to his table with a plate full of fried chicken. And I just watched him, thinking that despite the rhetoric, the vitriol and the trumped-up worries about Latinos destroying the town, even David Duke wants his chicken.

Shares