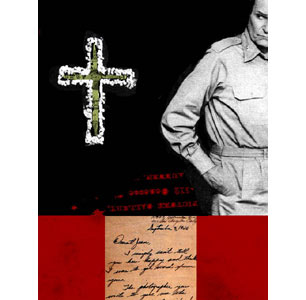

Some months ago I was just killing time, reading letters offered for sale on eBay.com, the online auction site. Some were penned by famous people — Nixon, Einstein, Proust — and commanded fabulous prices. But the letter that caught my eye was from a nobody to a nobody. It was handwritten and dated Oct. 5, 1918. It was from someone in the War Department and was addressed to one “Andrew E. Race, R.F.D. 1 Manchester Depot, Vermont.”

“Dear Sir,” it began, “It is with deep regret that I heard this morning of your son’s death. He put up a bully fight and it seemed until the very end that he must win. I merely write a line to let his father know that the son was a dandy little soldier and attracted the favorable notice of his officers from the first day that he arrived in camp.

“I know that I have lost a good soldier,” he went on, “and feel just as if I had lost a good friend. Every time I would see your son performing some duty I would … advance him for the willing and satisfactory manner in which he performed it. It’s a cruel shame and I’m mighty sorry.” The letter was signed “Charles J. Bellamy.” He was a captain at Camp Devens, Mass.

Something about the letter unnerved me. How could something so intensely personal as a letter about the death of a son find its way into e-commerce? I was troubled too by the utter anonymity of this soldier’s death. The deceased was not even named, though his identity was clear enough to the father in whose trembling hands this letter was once held. But that grief had long since been reduced to a mere archival curiosity. Less — a commodity on a Web site.

It seemed to me that a life, no matter how brief, ought to come to more than this. Who was the young man? What battle claimed him? Where was he buried? Did he leave behind a wife or children? Over the intervening 80 years all traces of his life had been expunged. He had now been consigned to the lowest rung of history, too obscure even to catch a legitimate antiquarian’s eye. The last remaining evidence of this young man’s tragedy was now the subject of a bidding war in cyberspace, to which I reluctantly added my own offer. The bidding began at a few dollars. Within days, the price had soared.

I became determined to win, though I had not the foggiest idea why. And in the end I did win. I scribbled off a check for $67.50 and waited for my prize.

The yellowing letter arrived a few days later by priority mail. It was still in the envelope from which a stricken father had sought comfort after his son’s death. I read it almost with a sense of shame, and tucked it away in a drawer where it remained for months, a strange trophy for which I had no discernible use and that made me feel like a ghoulish interloper. What had made me purchase another’s grief at auction?

I had all but forgotten about the letter until one day I came across it again and sat down to read it once more. I felt an irrepressible need to learn something about this young man, to know at least his name and the field in which he fell. As an investigative reporter, I fancied myself well equipped for the task. I telephoned Manchester, Vt., and spoke to the town clerk. I interviewed the caretakers of cemeteries. I queried a local historian. Everywhere I drew a blank.

It was an object lesson in mortality, one I already knew too well. My father had died 25 years earlier — at 50 — and already my memories of him were dimming. All that I have of him is a few tattered letters. I wondered if one day they too might find their way into the hands of a high bidder, someone oblivious to their true worth. So quickly life becomes artifact. In 80 years, all traces of a soul may be lost. Discouraged, and annoyed with my indulgence in purchasing the letter, I once again put it away.

But recently I again found myself poring over it, searching for clues as to the identity of the deceased. Once again I took to the phones. A kind librarian in Manchester searched local war records and found reference to a young man whose surname was “Race” and who had died on Oct. 4, 1918. His name was Waldo Andrew Race.

He was identified as soldier No. 2,722,703. He was with the 1st Company of the 1st Battalion, 155th Depot Brigade. Now I had a name to go with the letter. I learned that he was born in Bradford, Pa., and that he was single and a fine violinist. Why any of this should matter to me, I could not say, but it did. I pressed for more details.

From other records I discovered that Race was 23 when he enlisted, that he stood 5-foot-5 and had blue eyes and light hair. His complexion, too, was light. He had been assigned to Camp Devens and died there the day before the letter was written by his admiring captain.

He was not felled by a bullet but by the dreaded “Spanish Lady,” the influenza that ravaged America even as World War I was coming to an end. His military camp, Devens, was too close to Boston, an epicenter of the plague. Not that it mattered: The whole country was soon enough in its grip. His death in early October coincided precisely with the very darkest days of the pestilence that snatched some 600,000 Americans, far more than war itself had claimed.

I read the letter yet again. “He put up a bully fight and it seemed until the very end that he must win.” His heroism had displayed itself not against the Kaiser but against a virus. Records show that his father and mother were compensated for their loss; each received $15 every month for the rest of their lives. That apparently brought little solace to them. His obituary contained these words:

“The passing of a loved one is always full of grief but the death of this son of Mr. and Mrs. Race was particularly pathetic inasmuch as it was just seven weeks since their youngest son met his sudden death by being struck by a railroad train at the crossing near the station. The parents had been buoyed up by the hope that their son might be spared owing to his fine constitution but the long strain was too much for him.”

His remains were brought to the family home. There were no mourners beyond his immediate family. Because of the flood tide of new influenza cases, all public gatherings — schools, churches, even funerals — were prohibited by law. The Race house was filled with flowers from those who would have come in person had they been allowed.

There was nothing more I could learn about Race, except that he held the rank of corporal and that his grave is in Manchester Center Cemetery.

Over the years, the letter outlasted the family to whom it was mailed and finally came to rest at the bottom of a steamer trunk in a chilly attic just across the Vermont state line in New Hampshire. There, an enterprising fellow came upon it and saw at once its latent value. Now I, too, am belatedly coming to see its worth. In a curious way, it feels as though the letter was also addressed to me, that it held a personal invitation to which my own needs made me duty bound to respond. By my words now, his name is again, at least for the moment, in the thoughts of the living. That gives me some comfort.

Each June I spend a week in Vermont, fishing and teaching writing. This June I will also be paying a visit to the grave of someone I would like to have known a little better. His name is Waldo Andrew Race. Like all names, his is worth remembering.